Varanasi

Rediscovered

B. Bhattacharya

With 40 black & white illustrations and 12 maps

Munshiram Manoharlal

Publishers

To the People of Varanasi

Contents

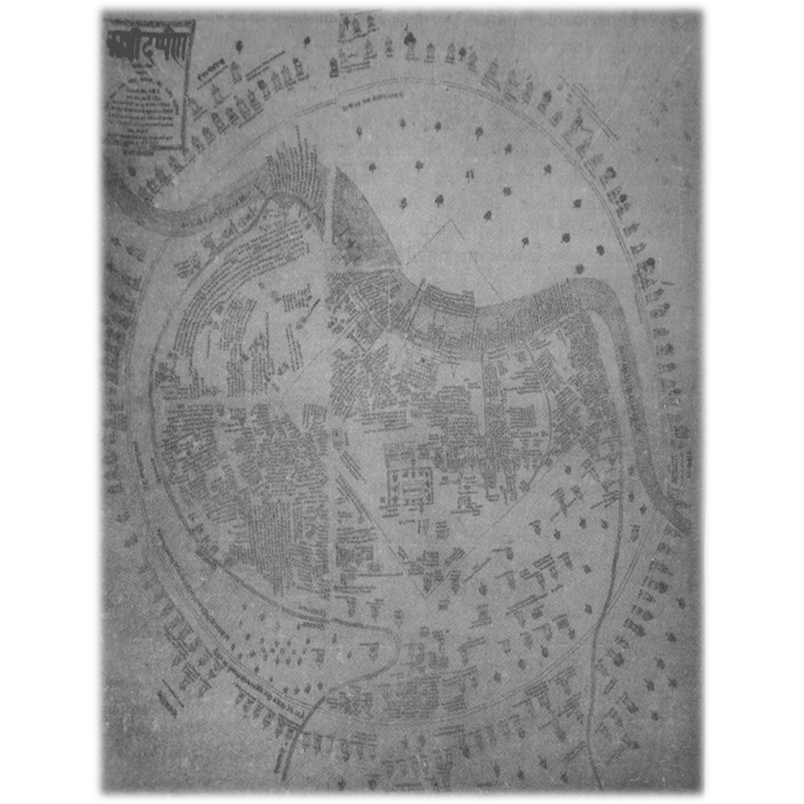

1. Kasidarpana: traditional conventional map still sought by pious pilgrims

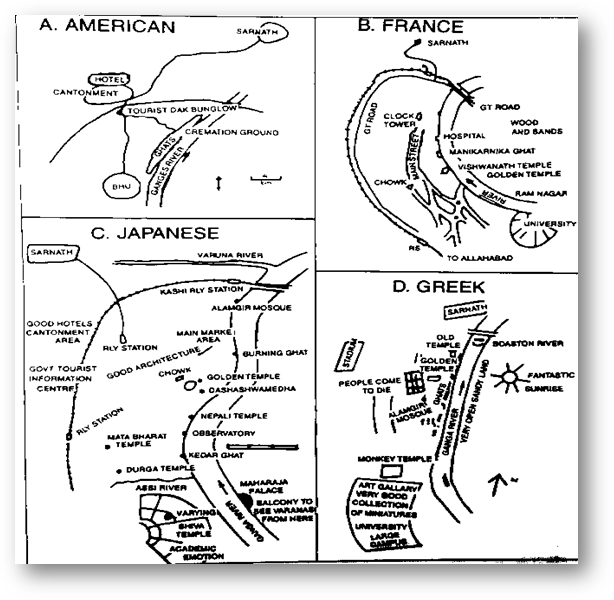

2. Tourists' sketches of Varanasi: American, French, Japanese and Greek

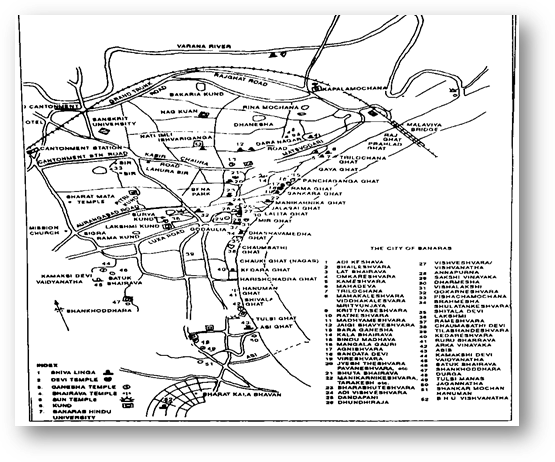

3. Varanasi: the city, showing temples

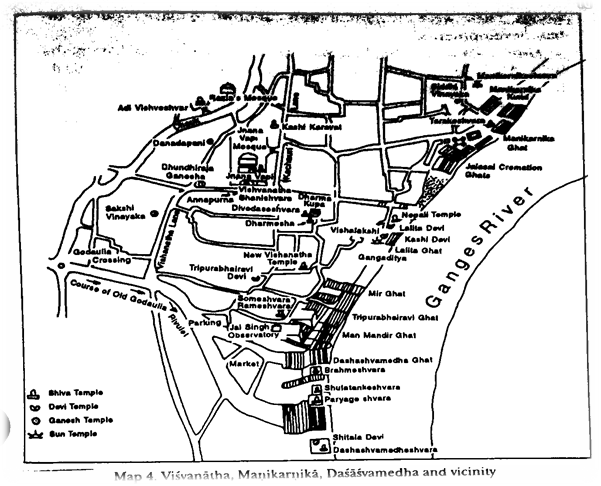

4. Visvanatha, Manikarnika, Dasasvamedha and vicinity

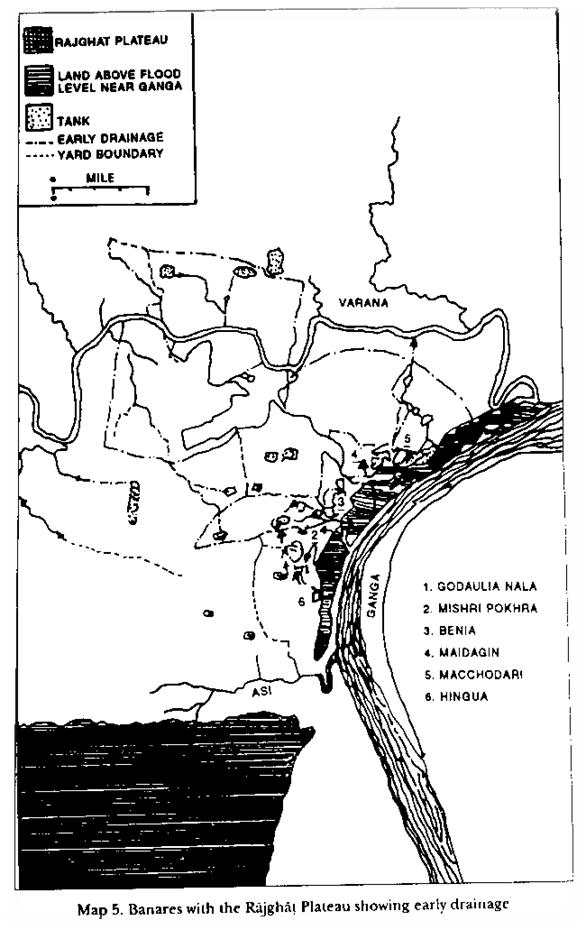

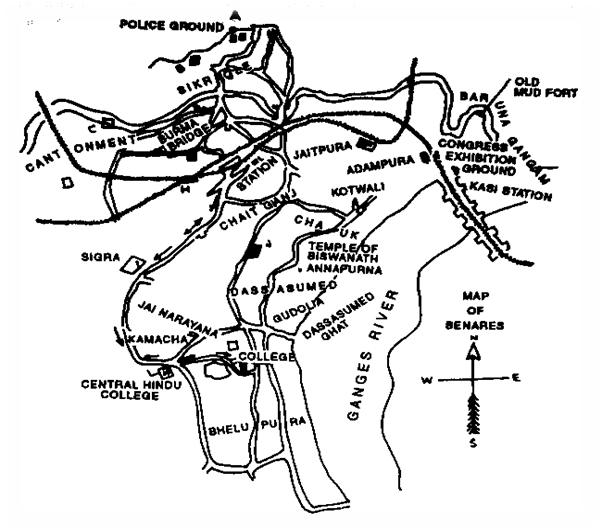

5. Banares with the Rajghat Plateau showing early drainage

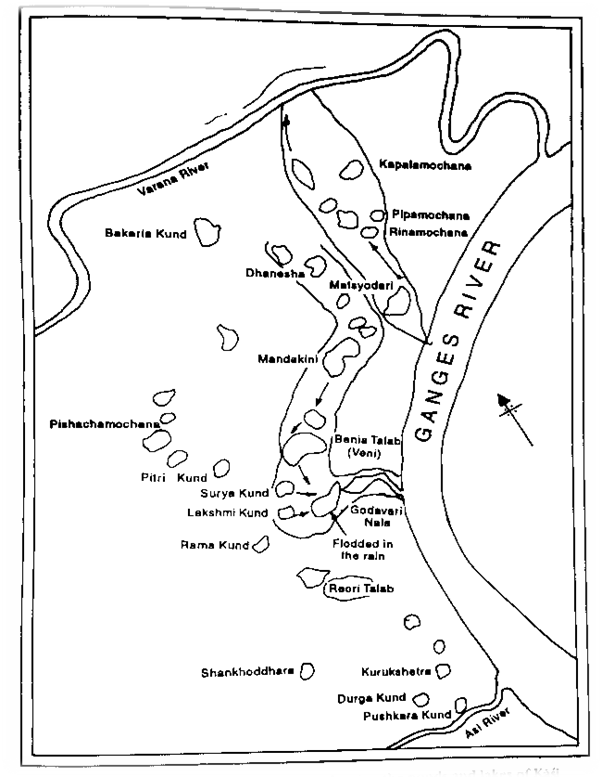

6. James Princep's map of Bunarus, showing the ponds and lakes of Kasi

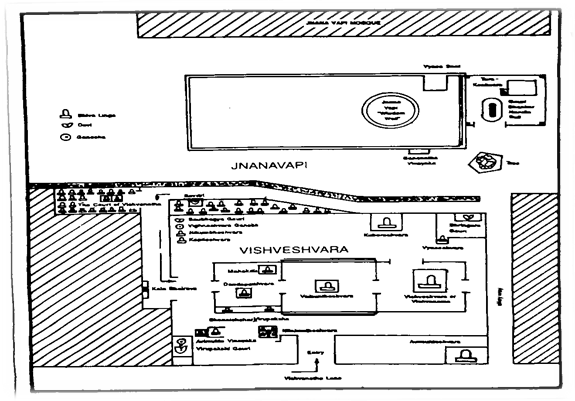

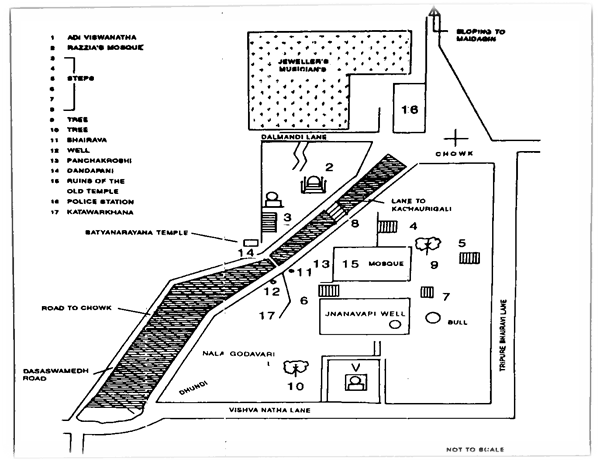

7. Jnanavapi and the temples

8. Chowk area-old and new temples

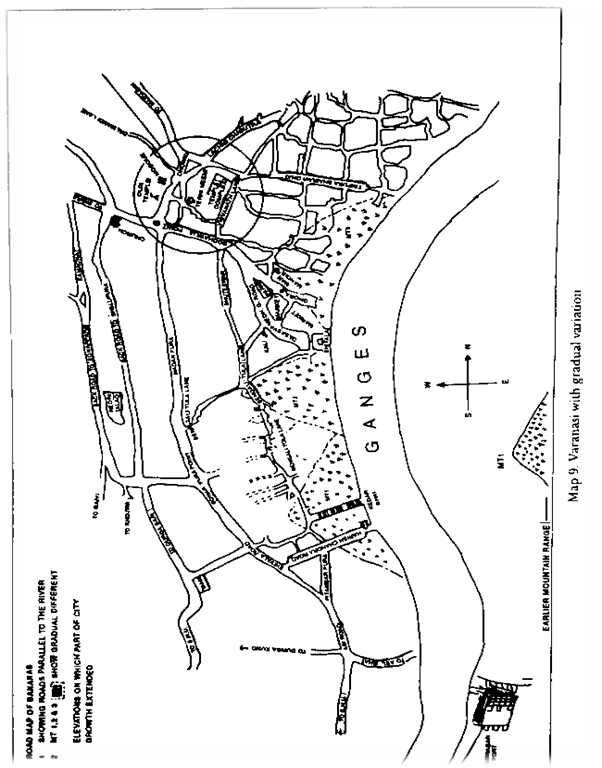

9. Varanasi with gradual variation

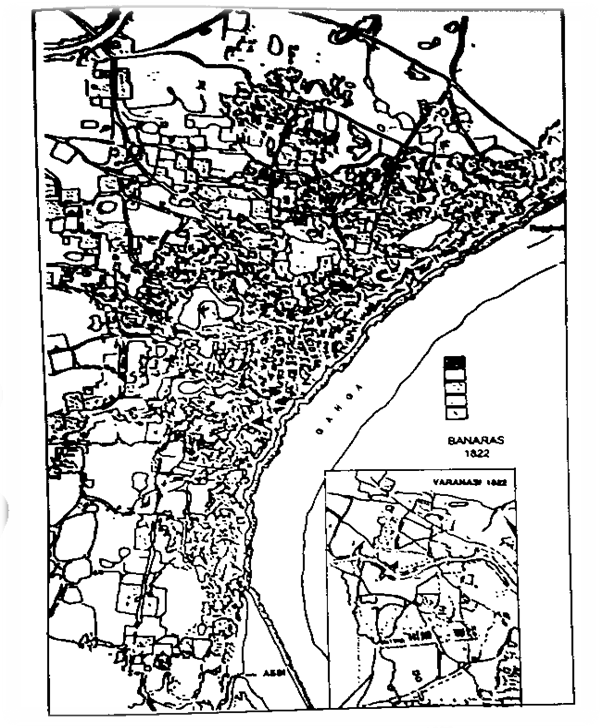

10. Development of the city: Banaras 1822

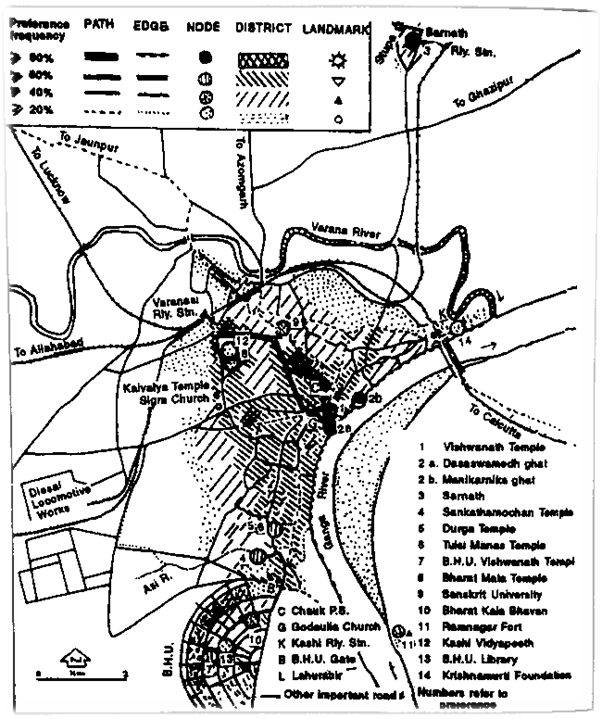

11. Varanasi: A composite cognitive map-sketch

12. A valuable old map of the extended city of Varanasi after the English disturbed it by road and railroad constructions

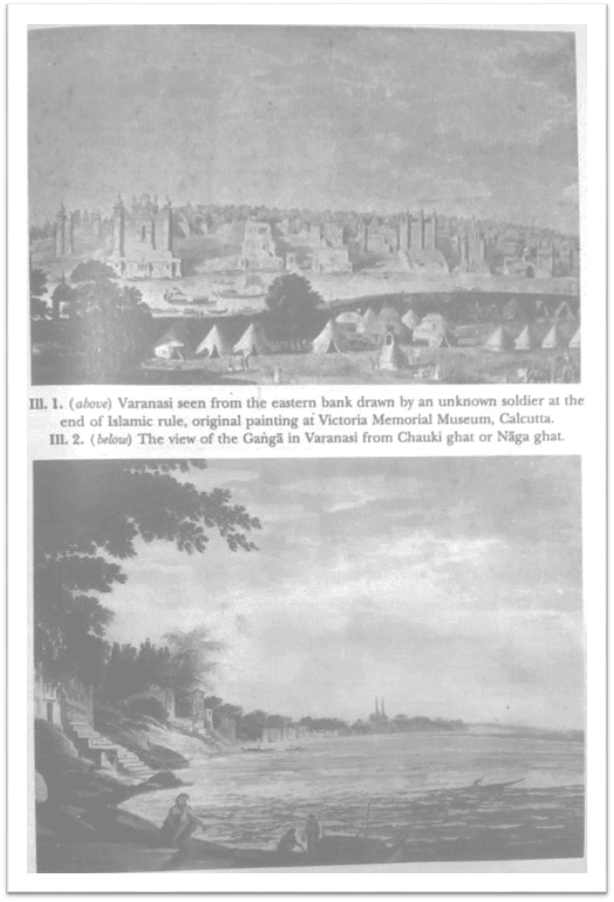

1. Varanasi seen from the eastern bank drawn by an unknown soldier at the end of Islamic rule, original painting at Victoria Memorial Museum, Calcutta

2. The view of the Ganga in Varanasi from Chauki ghat or Naga ghat

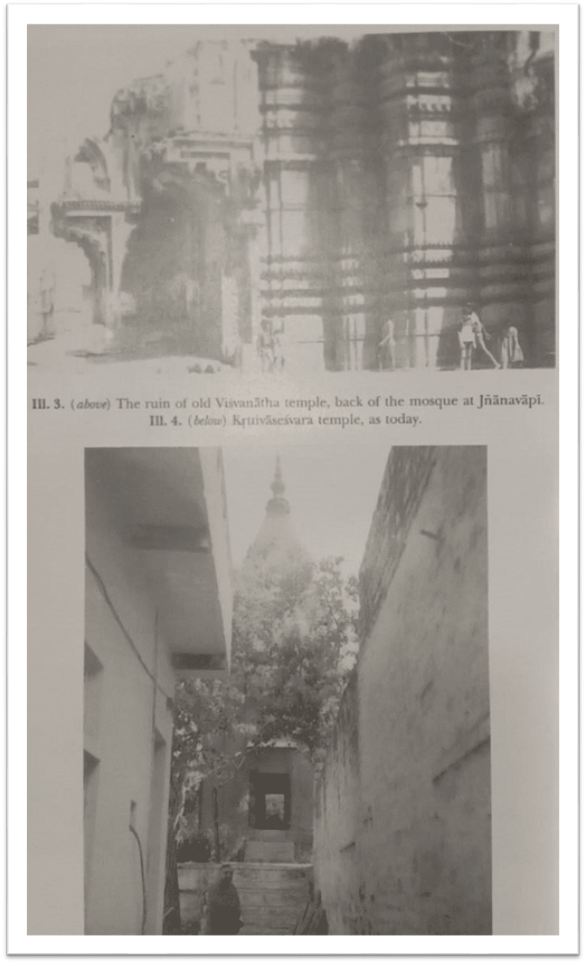

3. The ruin of old Visvanatha temple, back of the mosque at Jnanavapi

4. Krttivasesvara temple, as today

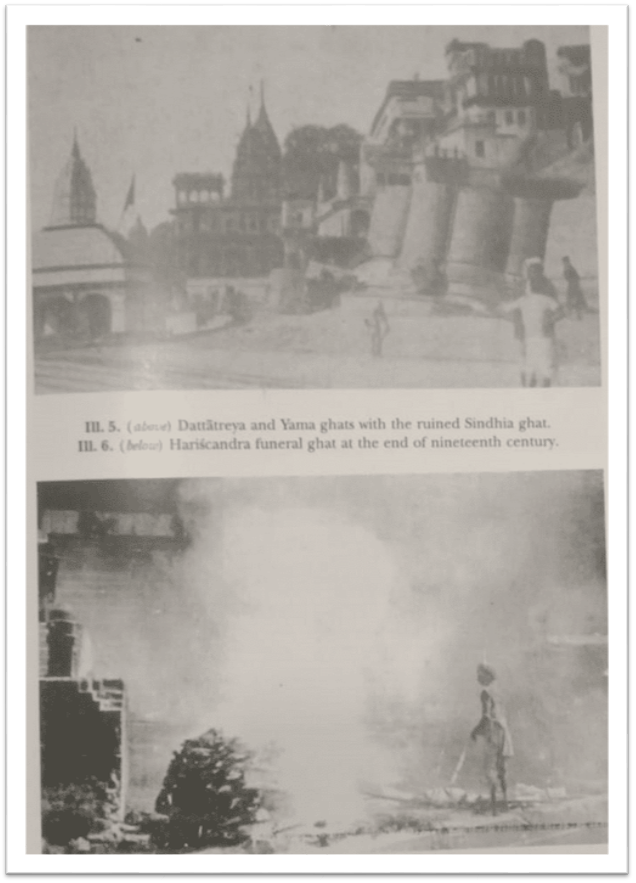

5. Dattatreya and Yama ghats with the ruined Sindhia ghat

6. Hariscandra funeral ghat: at the end of nineteenth century

7. Bakariakunḍa (Barkarikunda): picture taken late nineteenth century. Author saw this by 1929 and found it worse. Now there is no trace of the artifacts

8. Omkaresvara lingam

9. Monument to Rani Bhavani's glory: Durga temple

10. Monument to Rani Bhavani's glory: Durgakunḍa

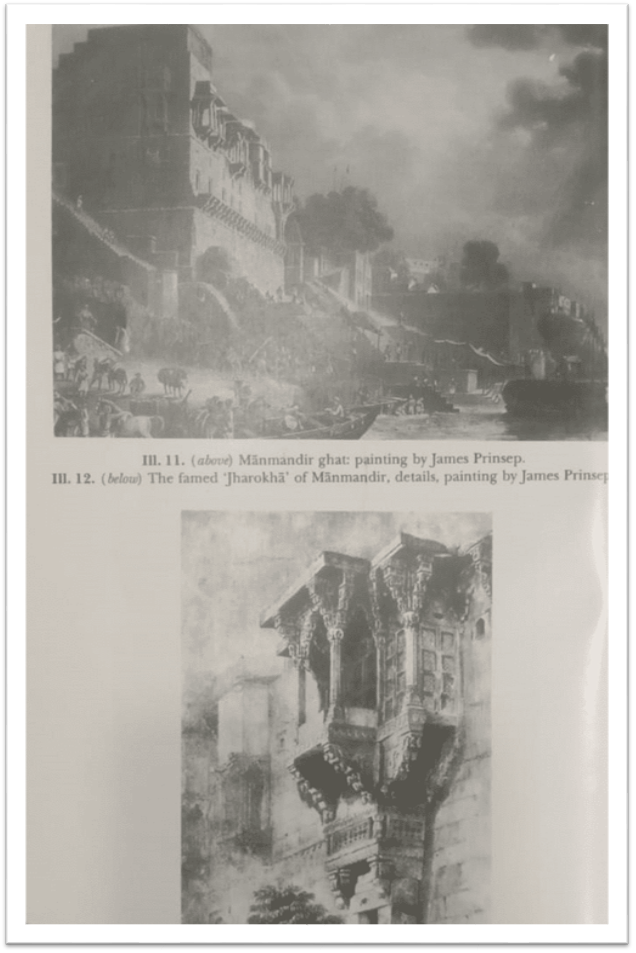

11. Manmandir ghat: painting by James Prinsep

12. The famed Jharokha of Manmandir, details, painting by James Prinsep

13. Nepali Khapra ghat, Varanasi

14. The quiet flows the Ganga

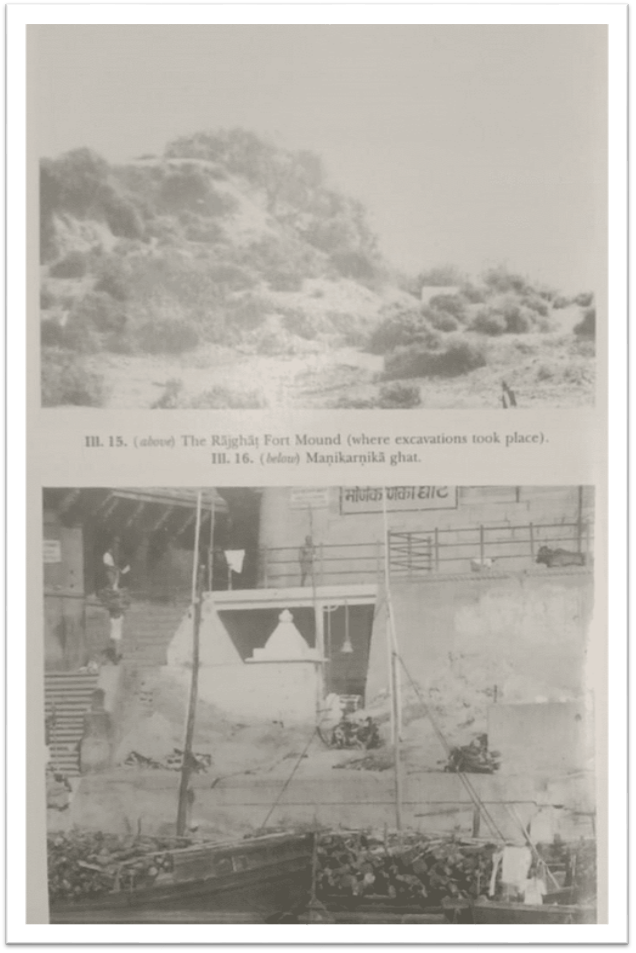

15. The Rajghat Fort Mound-where excavations took place

16. Manikarnika ghat

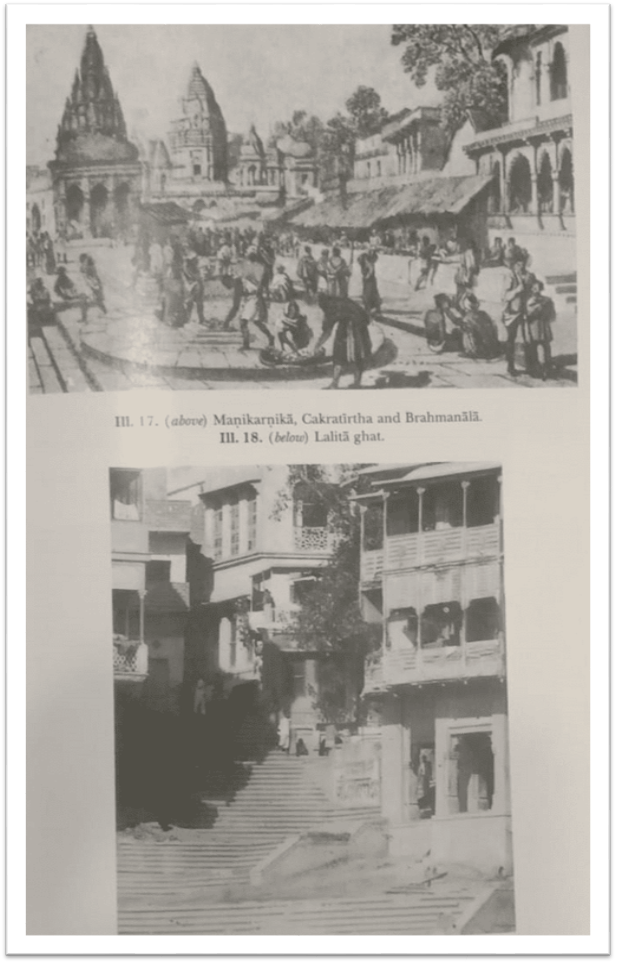

17. Manikarnika, Cakratirtha and Brahmanala

18. Lalita ghat

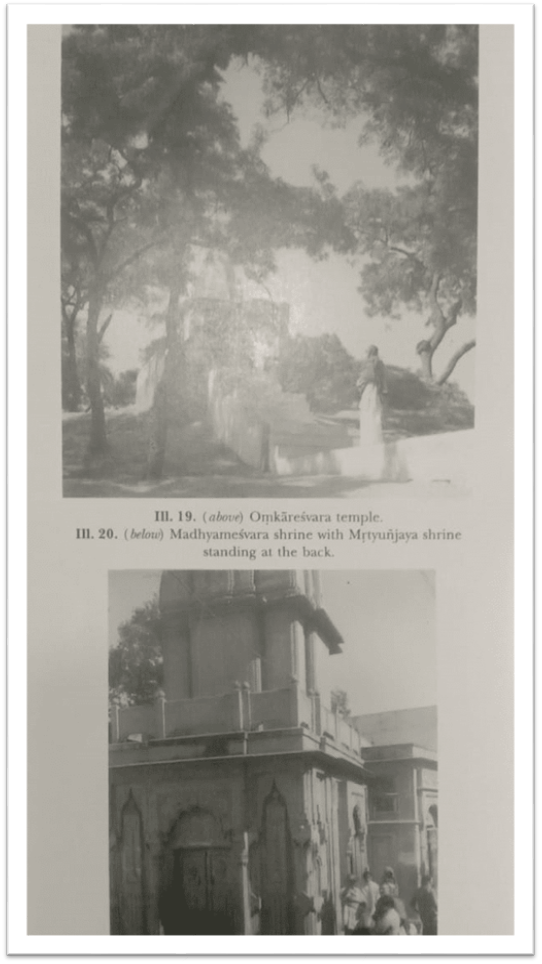

19. Omkaresvara temple

20. Madhyamesvara shrine with Mrtyunjaya shrine standing at the back

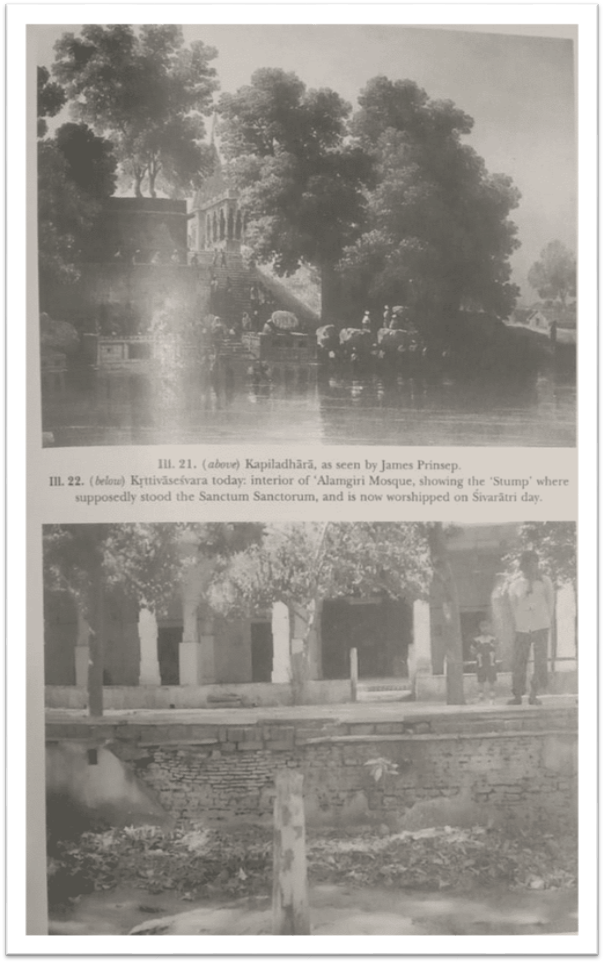

21. Kapiladhara, as seen by James Prinsep

22. Krttivasesvara today: interior of Alamgiri Mosque, showing the 'Stump' where supposedly stood the Sanctum Sanctorum, and is now worshipped on Sivaratri day

23. Adi Visvanatha on the Hill

24. The ruins of the Visvanatha temple as James Prinsep saw them.

Note the three graves

25. The great Mandakinitalao: drawn by James Prinsep. Bada Ganesa is supposed to be behind the right hand grove

26. The ever-watchful Bull Nandi of Jnanavapi

27. Balaji ghat as seen by James Prinsep

28. Bhima ghat as seen by James Prinsep

29. Dasasvamedha ghat

30. Pilgrims bathing at the Ganges (mid-nineteenth century) now.

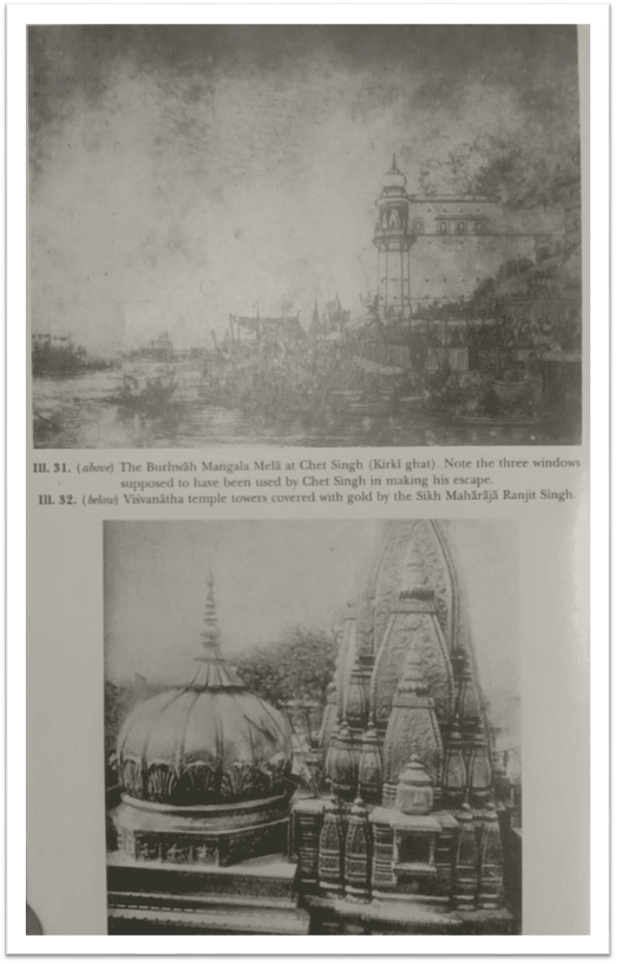

31. The Burhwah Mangala Mela at Chet Singh (Kirki ghat).

32. Visvanatha temple towers covered with gold by the Sikh Maha- raja Ranjit Singh

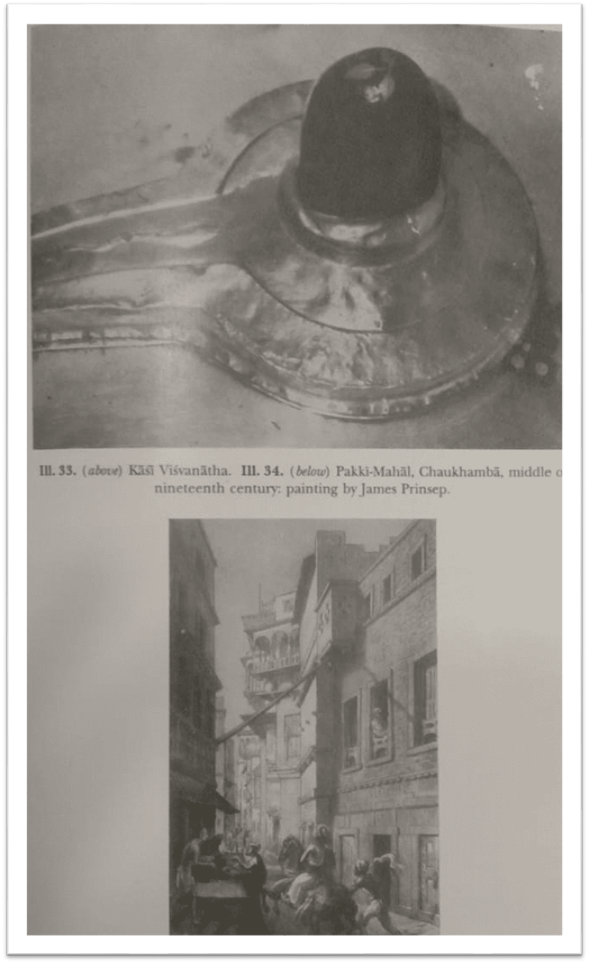

33. Kasi Visvanatha

34. Pakki-Mahal, Chaukhamba, middle of nineteenth century: painting by James Prinsep

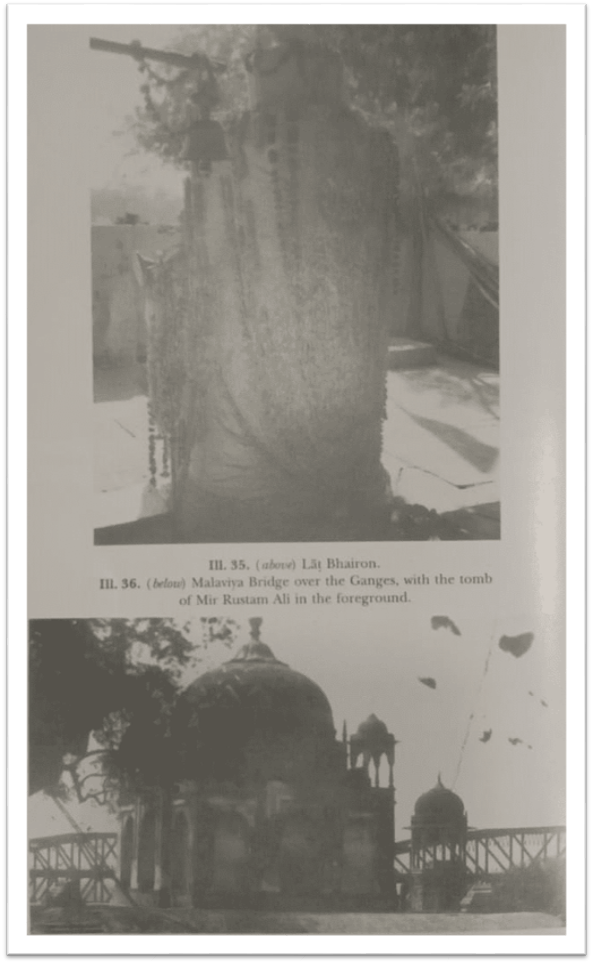

35. Lat Bhairon

36. Malaviya Bridge over the Ganges, with the tomb of Mir Rustam Ali in the foreground

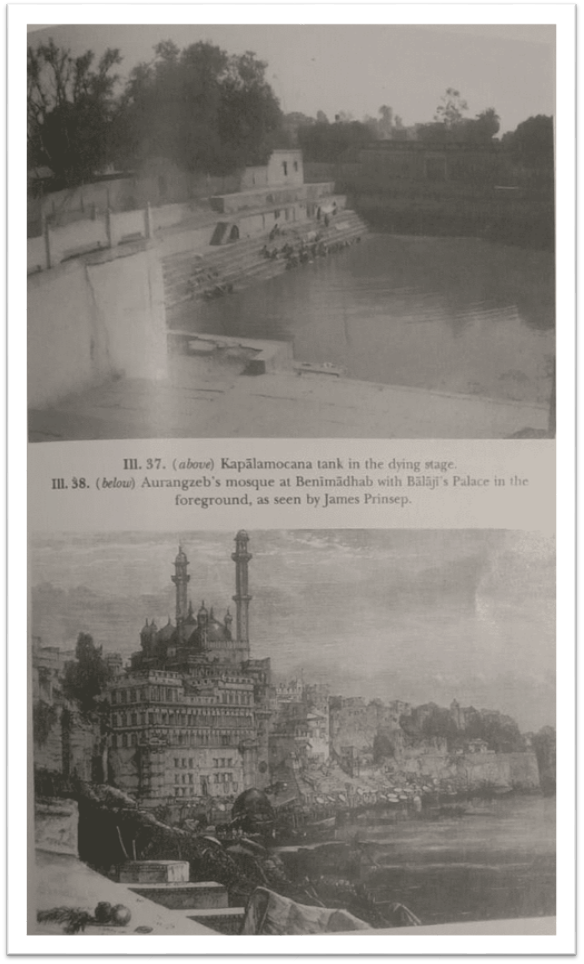

37. Kapalamocana tank in the dying stage

38. Aurangzeb's mosque at Benimadhab with Balaji's Palace in the foreground, as seen by James Prinsep

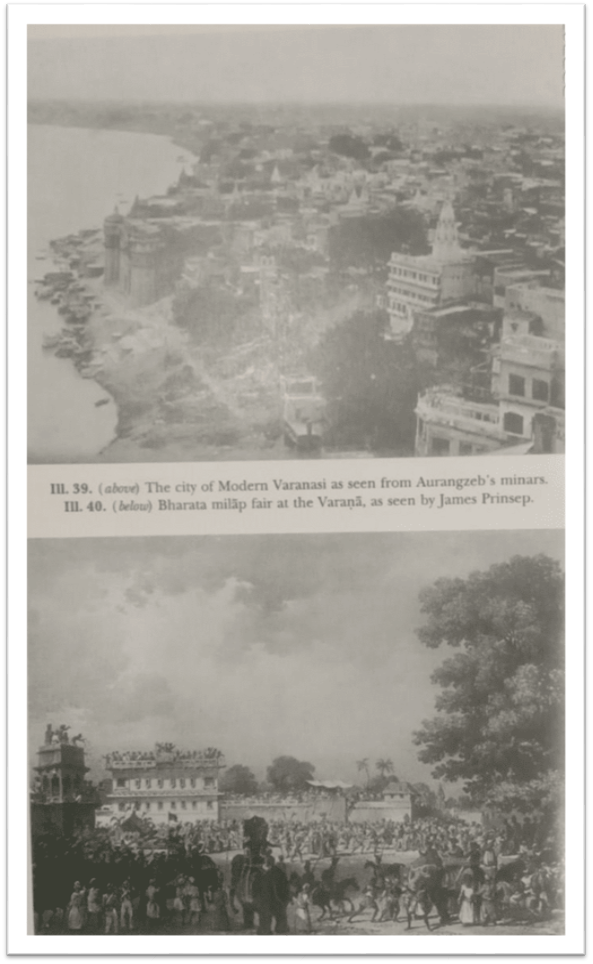

39. The city of Modern Varanasi as seen from Aurangzeb's minars.

40. Bharatmilap fair at the Varana, as seen by James Prinsep

There is no other city in India which evokes as much interest in mindful tourists as the city of Varanasi. This by no means is a modern interest. It has been running through the veins of India's history ever since. From the times we know of history, and the history of tourists in India, we find that traders, scholars, philosophers, wanderphiles from China to British Isles, from African to the Russo- German territories, even from the learned Arab lands the interested make a beeline for the renowned city of Varanasi.

The trend has not yet abated. In fact it is on the increase; and books after books are coming out on the charmed city of undying Varanasi, the gorgeous, the mystifying, the fascinating Varanasi, the oldest city that never loses its youth.

And most of those who had the luck of 'feeling' the throbs of the magic city have been itched by a consuming desire of keeping a record of his/her reactions of the first meet with the great city of the learned and the bold and frank.

The earliest books on Varanasi from the foreign pen are from the inevitable and unbeatable Chinese, and Arabs. Thereafter we have records from Africans, French, German and of course English travellers, officials, scholars. The literature on Varanasi includes photographers, etchers, painters etc., who found it irresistible to etch, paint, sing, ridicule the ancient city.

The list of books on Varanasi would fill pages. One of the latest comprehensive books, Varanasi, the City of Light by Diana L. Eck has introduced Varanasi to the foreigners who seek information on the city for a tourist's use. This author has done a commendable job under inevitable restrictions from which a non-Hindu, and specially a white lady has to work. Whereas she has accumulated a lot of information from such sources as came under her perview, she could not get herself admitted to those tucked away holes and corners which the confirmed Hindu alone could reveal.

One of the most delectable works on Varanasi comes from the pen of Dr. Motichand Kasi ka Itihasa, who could certainly have elaborated on the subject had, he had the opportunity of writing his treatise after Independence. Authorship during the British Raj was no easy matter, specially for a social critic. And history is nothing but the criticism of the times. His work, commendable and detailed as it is, could have been more critical and probing of the times and the social changes in Varanasi. But authorship during the British Raj for an Indian was a complex proposition and most of his writings was done before 1947. It was indeed difficult to adopt the stance of a social critic at that point of time. And history proves to be lifeless without a penetrative criticism of the times it deals with. History without a critical approach is no history.

There is a gem of a book, Kasidham, in Bengali published by a not too well-known 'press' in Calcutta (Indian Art School) by Manmatha Nath Chakravarty which throws much light on Varanasi for one who admires Varanasi. Written about eight decades back naturally the book indulges in some euphoria about glorifying in Hinduttuam, and upbraiding the non-Hindu communities, as well as speaking very high of the administrative skill of the English. Nevertheless, the quantity, quality and arrangement of the informations given demand credit for details and arrangement, provided some inaccuracies are overlooked.

Two small books on Kasi by Bisvanath Mukerji, and The Sacred Complex of Kasi by L.P. Vidyarthi, together with Varanasi: Down the Ages by K.N. Shukla demand critical notice from anyone writing on Varanasi. And of course the works of E.B. Havell and M.A. Sherring are today regarded as classics.

Yet this attempt may offer an excuse. It certainly avoids to be a repetition of what has been worked on before, and how. Yet it is not an original work in true sense of an archaeologist. The author has attempted to cover those grounds which, perhaps considered as too controversial, have never been treaded on.

It has gone more into what-s and why-s and how-s of the past of Varanasi. Varanasi's special character, distinguishing social norms, patterns, complexes, population-distribution, specially the antecedents of its multi-tenored human problems and human achievements reflected against the commanding cultures of the House of Oudh and the House of Balwant Singh, the Raja of Benares, have attracted the attention of the author more, than a mere recital of the names of temples, localities and ghats of Varanasi.

This book has tried to visualise Varanasi from the Harappan age to the present times, wading through the mass of details as offered by the invaluable Puranas, the indicative names of the localities, the forgotten and bedevilled natural landmarks of Varanasi, and make a volte face about the very position and placing of the city as we now know, and as we ought to know.

There had been many Varanasi-s; the city as it stands today betrays its accurate location which is no longer recalled today. The city even today recites a string of its names, without ever worrying to explain what those names would mean, and what historical indications imbedded lie deep into those seed words that reveal the new Varanasi, never before imagined by any other author.

This book proposes to lay a great store by the names of localities, and proposes to dig up the lost history, and reset the actual ancient city of Varanasi against a correct perspective through traditional changes of names, to which it still clings, in spite of the changed and changing names.

Similarly lost rivers and lakes localised by the Purana narratives, and the lost social conditions have been rediscovered through such important treatises as Girvana Padamanjari, Krtya Kalpataru (KKT), Tirtha Vivecanakanda (TVK), Girvana Vagmanjari, Kasi Mahatmyam (K. Mhtm./K. Mhm./K. Mtm.), Vividha Tirthakalpa, and of course Agni Purana, Vayu Purana, Matsya Purana, but above all Kasikhanḍa (K. Kh.) section of the famous Skanda Purana.

In preparing the typescript of the book I have been assisted by Sri Sankarsan Banik, and am obliged entirely to my friend Mr. Bikash Biswas who deserves an author's sincere thanks.

The 'Notes' appended to the text are meant for clearing up certain controversial and hazily grasped points, and directing attention to original sources.

New Delhi

Phalguni Purnima 1998

B. BHATTACHARYA

Map. 1. Kasidarpana: traditional conventional map still sought by pious pilgrims

1

I

Who does not know Varanasi? Or, who does?

Venice, Cairo, Baghdad, Damascus, Peking, Rome, names haloed in epics, lores, legends as 'ancient', sound 'modern' in comparison. All of these have been alive, and are still buzzing.

We are not speaking of dead cities: Thebes, Ur, Knosses, Troy, Persepolis, Bogoz-koi, Mohenjo-daro, Lothal, Kalibangan. We are not speaking of dead cultures.

Varanasi is a distant echo. Coming down from other times. She is still busy, alive, buzzing. We are speaking of this vibrant city. In speaking of Varanasi we speak of a functional town.

The glorified Aryan hordes had still been driving their horses across arid stretches and desert passes, in search for green acres and secured habitats far beyond the challenging terrains of the Caucasus, Elburz, Hindukush and Badakhshan,... still daring the sandy horrors of Dash-e-Lut, Sarhad, Baluchistan, and finally the formidable Thar. They 'came down like wolves on the fold.'

That indeed was a far away time. The Sarasvati still carried her crystal currents from the Himalayas to the Kutch and the sea through the holy village of Puskaravati.

The hungry riders having reached a land of milk and honey forgot their horse-flesh-and-beef years. They had arrived at agriculture and land settlements. They sang of Indra, Parjanya, Vasundhara (clouds, thunder, rains and productive earth).

These riders were other people with other patterns of life. Their sudden appearance had radically disturbed the natives of the soil, belonging to other times, more ancient and more conservative. These had been the autochthons, the indigenous builders of their settlements, all on their own. The hoariness of their past out-reaches the yardstick of historical time.

And Varanasi had met those hordes. Varanasi had out-aged the Aryans.

We of today could only faintly imagine how the autochthons, the settled of the land, lived their own system, part rural, part urban, part sophisticated, part nomad.

The gods these stone-age settlers believed in, lived in the skies and beyond. Their blessings poured in rains, and conferred fertility.

Their gods principally belonged to this mysterious forces of fertility. The power of heaven displayed mostly through human wombs, and their function. The pain-joy joy-pain syndrome of sex and reproduction held them in awe, and they worshipped the mystery of life.

On this placid pastoral tranquillity descended a cataclysmic disaster.

The distant far away clatter of thousands of unshod hooves had finally come to a halt. The hungry riders found a people living in peace, and making the earth yield their food in plenty. They decided to settle.

They settled on the new lands washed by a multitude of rivers. Today the good old earth has been disgorging the rude evidences of those turmoiled times through which the settled perished, yielding place to an yet unsettled mass of grabbers of the soil.

Townships laid through planned hard labour had been destroyed and consigned to dumb dust and wild howls. The Devas had demolished the Dasyus, and the Vedas got filled with descriptions of those sanguinary events.

The records say that Varanasi too could not escape her quota of misery. But Varanasi refused to be consigned to the silence of dusts. Molested again and again, she rose again and again from her humiliations and misery.

She rose to defy Time, and set a record in history for stubborn tenacity.

Varanasi was one of those forgotten cities, yet not one of them. Despite the years, the challenges, the thrashings, she has remained different. She is stubborn, unique. She refuses to die, to be effaced and to take to dusts.

She decided to achieve perpetuity in time through a liberal policy of accepting new norms, through a free admixture of ideas and blood. Varanasi, the orthodox, was not fanatic. Varanasi persevered through the most catholic of cultures, the 'Siva-culture'.

Since then Varanasi has been looking upon changes of the passing cultures in history,-the Greek, the Kusana, the Mongol, the Hūna, the Pathan, the Mughal, and finally even the English.

IMAGES OF VARANASI: TOURIST SKETCHES

Map 2. Tourists' sketches of Varanasi: American, French, Japanese and Greek

The good old Lady nods her hoary head knowingly, sage-like, and reduces the enormity of cataclysmic upheavals to mere surface movements. She pushes her beleaguered head through tonnes of. debris, 'bloody but unbowed'.

She is overly happy that she, the old bones, could after all main- tain her fort intact.

She the grandmother of mothers, accommodating all types of changes within her time-patched rags of ancient glory, and glittering garments of moving patterns of many faiths and cultures, continued, as of old, attending to her familiar chores of life, abounding and unending, nonchalant, undisturbed and profound.

As history passes, Varanasi smiles, and smiling survives the mutation of Time.

'Time the Fearsome' (Kala-Bhairava) is the Guardian Angel of Varanasi.

The life throb of other ancient cities touches us, if at all, very faintly. Names such as Tutenkhamen, Sargon, Gudea, Nebuchadnezzar, Assurbanipal, Shehrezadi,-the Hsias, the Chous, China-names that made history in the East and the West, soothe our chronicle- loving ears with faint melodies wafted from a very distant past. The sounds, and the associate pictures lift us away from our fevered existence and mental maladies, and carry us to other times and other livings. When man thinks of the past, unknown to himself, he permits himself the luxury of a little roominess, and advantage of spaciousness. The distant past breathes of romance and freedom.

The very unreal-real nature of past's hoariness covers over strained nerves with a kind of drugged dream.

But Varanasi in comparison is more hardy, sturdy, stable, and grotesquely stubborn. Varanasi is matter of fact, and a sheave of fiction. Varanasi is orthodox unorthodox. Varanasi is die-hard, stub- born, liberal and informal.

Varanasi 'is', because Varanasi has always been there, a mortally immortal city, a wounded defiance, a challenge to Time.

But the tragedy is that we have been living in poorer times, when piety is a dying cause, faith an anathema, and soul a haunting chimera.

The changes in our times have hit Varanasi hard; and in hitting Varanasi hard it has hit our soul. Our present has become a threat to our future. We had been accustomed to live in hopes. Now we live in fear and frustration.

Stunned by entirely undeserved heavy and fast blows from a stark modern technocratic system, humanity helplessly stands amidst a shambles of its dream palaces. The cherished hopes for Man lies in splinters like fallen chandeliers. Man gropes and grovels amidst the ruins of his own making, looking for a spark of light.

Harassed by fear, choked by sulphurous skies, haunted by planned but meaningless devastation and mass murders, organised by systems perfected through science, Man stands at a land's end, and faces a traumatic situation of cliff hanging brinkmanship.

And this is the kind of life we propose to bequeath our posterity. It is a future killed by the present.

We look for a god that is not. Like 'Jerusalem Undelivered' we look for a Varanasi that is not, and yet is.

We search for a faith lost through overspreading; and our widowed hopes reach for a new redemption named Varanasi.

Varanasi retains that lost soul, despite the thrashings she has undergone.

In searching for the lost Varanasi we search for our last souls.

II

As members of a community we naturally hold on to the ancient. Our past is our support, root, faith, bastion and escape at the same time. Our past is a dreamland we want to visit again and again.

But Varanasi is more than a belief and escape. It is as firm as a living faith. If we have to continue and live, once in life we have to feel in our fevered nerves the bygone spirit of Varanasi.

In the name Varanasi coexist peace and logic, the ancient and the living, fanaticism and liberalism. The lonely, the crowdy, the purifying, the petrifying, the elevating, the degrading, the stubborn, the relaxed, the firm, the crumbling all thrive side by side in Varanasi. Varanasi is Time's caravanserai.

Like love, Varanasi too has passed through its inevitable phases of wax and wan, new and old, dream and trance, faith and scepticism, life and death, promise and betrayal.

The price that modern life has been called upon to pay for a quiet simple existence is too dear. Dear because life has lost its essential value. Life is held too cheap.

But are not ruins the ideal fulfilment of all vaunted designs? Is not cynicism the ultimate of religious fervour? Ruins tempt and urge discovery. But is indeed discovery relevant? Homer's Odysseus-com- plex, so eloquently and picturesquely versed, finally touches a white truth that there is indeed nothing to discover. Man and nature basically remain unaltered.

Yet Varanasi demands discovery. In discovering Varanasi we dis- cover a human heritage, for of all the ancient prehistoric human habitations, Varanasi alone remains fresh and bustling, and com- pels attention.

Why?

Because in Varanasi the common man's good and evil has got so mixed up that it is difficult to pick clean values without colliding with the crossbreeds of ancient cants, and not too ancient credos.

Varanasi's long history ideologically presents a sordid picture of ruins of many futures. The durability of Varanasi's reputation is based on people's faith in reality of values.

There is an allurement inherent in subjectivity of thinking. This leads us to reflect on the interplay of belief and faith. In its turn, this again compels thought to determine the role of values in seek- ing a peaceful life.

Varanasi still assures and guarantees peace, the last quest of Man. Amidst all these contradictory but absorbing facets Varanasi, the Eternal, retains her undying virtue of continuity. It emanates a message that still lures the sick and the spirited, the demented and the meditative, the despaired and the reject, the scholarly and the religious, the idealist and the cynic.

This is why Varanasi still continues to be the most attractive and compulsive 'must' in a tourist's calendar and a pilgrim's itinerary. It is simultaneously a retreat for a recluse and a hermit, and a diversion for the eccentric and the pervert.

Weird sex, filthy lanes, indiscriminate crowds, vulgar decay, open raw filth rotting by baskets of flowers and trays of food,-verily Varanasi is a many-breasted Artemis.

At every twist and turn cats, curs, cows and crooks unconcernedly cohabit with priests, paupers, princes and prostitutes. By park-corners, lane-bends and river banks a thug dramatises, a bereaved weeps, a bull ambles by, or a mad man howls obscenities. A hearse passes, while a wedding procession merrily winds along, beating drums and blaring brass trumpets. Mad dervishes sing their charm- ing melodies. Bereaved widows howl their dirges. But unconcerned, the hot pastry sellers hawk their wares. A blind singer seeks a cop- per; a pious seeks a lingam; and a fraud looks for its latest victim.

Values brush shoulders in the labyrinthian past, and confusing present of Varanasi. The contemplative, the spiritual, the abnegated, the emancipated bathe in closest proximity with the dirty, the rus- tic, the beggarly, the sick and the maniac. Differences of sex and age, of sectarian exclusiveness and religious distinctions get merged in the constant flow of the blue waters, of the sacred Ganga,-cool, deep, perennial and primordial.

Varanasi is Ganga, Ganga is Varanasi.

Varanasi elevates, Varanasi depresses. Varanasi is free and gay. Varanasi is desperate and morbid.

Lumbering bulls, dilettante donkeys, degraded lepers, comic monkeys, coiling cobras, illusive soothsayers, pestering beggars, apa- thetic clairvoyants dreamily stream past the crowded lanes with supreme unconcern.

Varanasi rejects all forms.

Varanasi was born old. Age has not forsaken her; youth never touched her; time has not withered her; exposure has not robbed her of hidden charms.

No brush of Turner ever played on the mystiques of her river front. Cold cameras could not contain her soul, or cover her open- ness. Repetitions have failed to rob her of charms. Time has failed to make her go stale, lose her delicate savours, or pale her native hot tang.

The magic of Varanasi continues to bewitch equally a hard core urban cynic, a know-all university archaeologist, a philosopher, a scholar, a sage, a meditator, a nautch girl, and an enlightened saint.

Staying in Varanasi is a spell-stunned experience in a Time-capsule organised by a spiritual Hitchcock.

Over all these phases hangs of a powerful human drama, like the lighted ceiling of a modern theatre, the unseen but enlightened Angel of religion and piety. For in spite of whatever contrary has been said about it, man's urge for a religious relief is as true as man's response to pain. Steady devotion confers peace to a belea-guered soul.

As long as man would need survival, man would look for a religion of his own.

Religion is fundamentally the lonely man's only companion. Lone- liness is the ultimate of human living. Loneliness is a basic ingredi- ent for creativity. What man lives by in his lonelier hours is a man's personal religion.

Religion is a shrine of survival where man has to provide his own light.

The subjective idealism of religion alone has discovered, main- tained and preserved the moral vista of values, without which religion's powerful authority would crumble to a handful of dust.

The overcrowded loneliness of Varanasi acts for the religious as a cave does for a yogi.

III

The natural obduracy of Varanasi refuses to submit to the humiliation of decay. She refuses to disintegrate like other cities of prehistory. She rejuvenates her virginity with each rape. Wrecks, under which a lesser would long have been buried, have actually been lifted by her into monuments of glory and added faith. Each wound inflicted on her body has smarted her to attain a heftier recovery and made her gain an added vigour. Recessions replenish her; deluges fertilise her; death reincarnates her.

The breathtaking nobility of her fantastic river-side-beauty has inspired poets to string verses, artists to draw and paint, music makers to sing, and photographers to gawk and shoot.

What Varanasi loses in not nursing a Turner, she retains in her cherished troupe of genuine scroll-makers. The meek scroll-makers of Varanasi-lanes have not remained idle. Varanasi has no Strauss to record a Blue-Ganga. But the songs on the Ganga in Varanasi have been recorded from the primordial years in languages far more ancient than Sanskrit. The Vedas sang of the Sindhu and the Sarasvati; but Pali and Prakrta sang of the Ganga, the purifier of the degraded and of the outclassed, patita-pavani. She was called divyadhuni, the shaker of the celestials, and destroyer of the Vedic pride. No Apabhramsa branch of the vast subcontinent has missed to glorify the Ganga, the divine stream, the mother of rivers.

We feel both surprised and proud that the very name of Ganga (corrupted by foreigners into 'the Ganges') is derived from a language which had been the basic lingua franca of India, Munḍari. Much before the Vedic Sanskrit had superimposed its elitist sway over the common people of the subcontinent, 'Ganga' meant, as it still means, a 'river' in Munḍari (Ganga).

A legend recorded in the Mahabharata records that the most il- lustrious of the families of the Vedic Aryans in India had come out of the wombs of a Ganga-Girl, who must have been a non-Aryan, probably an unnamed Munḍari, for the subcontinent had been peopled with such indigenous communities as Munḍa, Bhara, Suir, Kol, Ho, Biror, Gond, etc., all considered under an omnibus name, the Nagas (the Dravidas, the Dasyus etc.). Songs on the Ganga and Varanasi are sung in all of these languages, most of them pre-Vedic. Some of the most touching songs on Ganga have been composed by Islamic poets.

While songs about the Ganga and Varanasi still continue to be sung in all the Indian languages, and even in dialects, pictorial records have been scarce due to ravages of time. This is not the case about sculptures. Ganga has been variously sculptured in stone and terracotta. The two great and significant examples stray into my mind, the one in Mahabalipuram, and the other masterpiece in the Ellora cave.

But Varanasi and her artists maintained a tradition in painting. Most of the Varanasi artists of old as well as of today, had a passion for painting on the mud walls of their humble tenements. The tradition still is alive in Varanasi.

But whilst paintings on distant Tahiti's mud-walls have been preserved at great pains by a responsible people's government of the French Republic, the wall paintings of Varanasi have been cynically consigned to cold oblivion.

Elitism and á bureaucratic chill, together, make the most effective killer of any art forms.

Some modern artists have attempted to preserve the glories of the Varanasi panorama. One such artist, an obscure soldier from the warring camp of Sir Robert Fletcher (15 January 1765) has left a very valuable painting, of the early Varanasi panorama as seen from the Eastern bank. Sir James Prinsep (1831) has immortalised his brush by leaving to posterity his graphic sketches of the Varanasi life.

These valuable paintings describe Varanasi as stood at the end of the Mughal times. Fletcher's painting had been lying in total obscurity in England (probably carried by the painter). The Indian Historical Society having got the winds of the painting, acquired it; and it still hangs on the walls of the Victoria Memorial Museum in Calcutta as one of its proud possessions.

IV

But is that all? Has Varanasi no other prehistory?

Varanasi must have started her steps across prehistory hundreds of centuries away from the period of the so-called 'available records'. She must have started her fledgeling life before the mud builders of Harappa and Kalibangan had ever heard of the Aryan Menace.

The records of those doleful devastations, of the most complete and humiliating subjugation of one people by another have found expressions through Rgvedic rk-s, certain social norms, and certain coinages of Brahmanical invention.

The Mahabharata is one of our valuable source-books, where in a chronicle-form we could trace the story of this humiliation, ending up with not only usurpation of rights, property, women and even religious forms, but also with the formation of a social group known as the dasas, or semi-slaves and serfs. The habitual dearth of women amongst the advancing hordes was replenished by a system of taking women as prisoners, presenting them as valued gifts. "Born of any woman an Aryan's child was an Aryan", said the law-books.

But it would be a mistake to rely completely on the Epic in its present form because of the mutations and mutilations it has been subjected to over the years from the Bhargavas, a specialised group of scholars appointed for singing high of the Aryans at the cost of the indigenous people who were made to lie low.

We are forced to accept that the Epic is, ancient as it is, but a fragmented and re-narrated document of a much larger bulk, which has been purposely destroyed, mutilated, or simply given up for lost in course of time.

We are in doubt. We have reasons to doubt. Were these indeed lost?

It is pertinent to enter here into a digression and state that one of the students or disciples of Krsna Dvaipayana Vyasa, the writer of the epic (Vyasa is not a name, but a patronymic, an appellation that describes a 'school of studies', and a special form of narration of chronicles), known for his up-dating revolutionary thinking, and Yajnavalkya one of his students, came by a life-and-death controversy about the way things moved; and in utter disgust and anger the latter left the academy of Vyasa in protest.

Yajnavalkya, the Vedic protestant, organised his own academy with 'tribal'-s for his pupils. These were the Tittiras, a tribe with the patridge (tittira) as a bird totem.

Even in those days this must have been considered revolutionary. Yajnavalkya wanted to get rid of the connivance of the Bhargavas who added and subtracted from the age-old chronicle known as the Jaya, a fragmented form of which is the present Bharata, or Maha-bharata.

Whilst the Bhargavas kept to their games of playing with the text for edification of Brahmanism, Yajnavalkya kept himself busy in forging a weapon of much telling intent. This was the compilation of 'the Yajnavalkya Code of Social Conduct', which runs contrary to the codes of earlier law-makers, Manu, Atri, Visnu, Harita and Gautama (not the Buddha).

The 'Yajnavalkya Code' became very popular because it looked after the interests of the changing times, and reformed society. The people hailed it, for it made wide room for accommodating the original non-Aryans within the large Aryan commune.

The point is that even in those far away times, when the epic narrative had been laying its foundations, the blatant Brahmanical slant, as opposed to the Vedic, had aroused protest; and Protestants to 'the cause' stood apart, and held their forte.

At any event the fact that the present Varanasi-range along the Ganga and the Varanasi ravine had been originally inhabited by a people of non-Aryan descent has been established by (a) stone implements characteristic of a Stone-Age culture; (b) special kinds of paltria and (c) toys discovered at different layers of excavation, which, incidentally go up to 14 layers.

This famous township still retains within its language, idioms, subtle turn of life-lure, clan, a typical non-Aryan freedom from form, and a spirit of total participation in social events. The Banarasi way (an euphemism for a happy-go-lucky, 'devil-may-care' non-Aryan way) still persists within its society, Hindu or Muslim. Such a 'rudely' frank exposition of life actually claims its descent from clans such as the Bhandas, Bharas, Suirs, and Avirs, all 'native' tribes, who lived in and around the hills and forests, now known as Varanasi.

We have to allow this fact to seep into the deepest recesses of our consciousness in order to appreciate why and how the ways and modalities of the Bhairavas, the Saivas and Tantras became synonymous with Kasi-ways, and why and how Kasi-Varanasi is regarded as the cradle and nerve-centre of Saiva rites.

The phenomenon has now been established by scholars.

As we are on this topic of interference with faithful recordings of events, we may refer to yet another significant anecdote contained in the Epic. This concerns the so-called appointment of an animal- headed Gana-devata (the spirit of the people) with many hands, as a scribe, amanuensis, secretary-stenographer to the narrator Vyasa. (The animal head of the scribe need not confuse us, as it indicates the usual Aryan slant against totemic tribes and local people, the multiplicity of hands indicating popular participation of many hands, and synthesis of many forms.)

Meticulous scholars of the epic know that the story of the appointment of an amanuensis is in itself a clever subterfuge on the part of later interpolators for indicating the participation of the local's in actual chronicling. Mahabharata researchers raise a point, if the legend of the appointment of an amanuensis has not been mounted later.

In case it is indeed a mounted interpolation, then our doubts cast even deeper shades. The Brahmanical Bhargavite texts having had their run, had been so effectively challenged by the proletariat scholars that the hands of the 'mass spirit' of the Gana-devata put a stop to an extremely clever scheme.

We shall see by and by that Ganesa is actually the Yaksa king Kuvera's 'other form' as a strong guard for vindicating Siva's rights against Brahmanical thrusts.

This democratic intervention shows that the mutilation and interpolation of the original text was not allowed to go unchallenged.

In any case we could read between lines, and infer that the lost Jaya had contained glorified records of the non-Aryan people of the land. (Had that story been left intact, would the history of the Harappan culture and its script have remained a closed chapter to us?)

The records of Aryan repressions, and of the glories of a local people had to be eliminated from so important a document.

The Epic was reorganised to sing of the heroics of the new peo- ple who did not hesitate to propagate, and 'increase their tribe', by extensively using the local wombs of spicy beauties such as Matsya- gandha, Paramalocana, Ganga, Anjana, Kunti, Hidimba, Jambavati and many others. The systems of acceptance had to accommodate both anuloma and pratiloma unions (union between upper and lower classes.)

The very basis of the social class-systems, and the urgency with which this has been defended, could be traced to these intermixtures of peoples. Viewed from this angle, acceptance of the caste- system as an excuse for maintenance of the purity of blood appears to be both unrealistic and untenable. But as a handle to keep Brah- manism and the Brahmans at the tops, the system had proved to be extremely effective.

The bitter truth has to be swallowed, because the process of attri- tion was a long one, and varied; the truth could not be just wished away.

Hundreds of folklores, legends, stories, kathas bring back to us sad memories of the total destruction of many cities, many peoples, many villages, and subsequent occupation of the lands, and subjugation of the victims, keeping them as vassals, serfs, slaves, as suited the situation. Epics have been written on the theme. Gods have been made of men, who had planned these massacres and devastations, the like of which the world has not known since. (The burning of the Khandava forests, or the devastations in Janasthan are cases in point.)

Skeletons of strings upon strings of populated settlements are being now excavated all along the river valleys of the vast subcontinent. They expose a kind of devastation that belies Vedic claims to peace.

After the dusts of the mêlée lie settled, the streams of blood are allowed to fertilise the earth, and the war crises finally die out, we could take a second look at history, and find that the amazing Varanasi stands her ground unchanged and unchangeable. She Varanasi, the eternal, stoutly stands her guard.

No Aryan thrust could unlodge the grips of the Ganas on Varanasi. There are several anecdotes in support of this.

Those war-torn centuries, however, have left their marks in their own way, usually forgotten, but not undetectable.

The traditional honour to Ganesa (and that of Hanumanta, the Mahavira) is one of these. Varanasi has been placed under 'guards' of one series of Ganesa-s, and another series of a far more sinister and jealous nature. These are the Bhairava-Sivas. Together they guard the environs of ancient Varanasi as 'Witnesses' to those ravaging centuries.

There is yet another set of shrines peculiar to Varanasi. These are half-accepted, half-spurned. These are the very popular 'Bir' shrines, number of which dominate localities all over Varanasi. These indicate non-Aryan antecedents, and even today these are extremely popular amongst the folks who are considered to belong to the lowest ranks of the caste and outcaste ladder.

Matsya Purana (183.66) refers to the King of the Ganas/Yaksas to have been accommodated by Siva as his main 'guard', when he was turned into Ganesa. This shows that Ganesa was a Yaksa, or a deity of the pre-Aryans.

We come to this topic later. Here we only note that Siva’s control over Kasi against the Aryan thrust is still recalled by the many Ganesas spread all over Varanasi. (We shall return to this topic.)

The Vedas and the Puranas are full of the accounts of these bloody feuds. So far as Varanasi is concerned we hear of the flights of Puspadanta, Ekadanta, Kalabhairava, Vakratunda, Nandikesa, Dandapani, coming down to Pratardana, Pradyota, Divodasa, the Haihayas and Ksemaka. Agni Purana and the Kasikhanda section of the famous Skanda Purana narrate accounts of the battles. Up to the end of AD 998 the Haihaya-Kalacuri and Pratihara wars kept Kasi menaced.

But the Vinayakas, Bhairavas, Ganesas, Kalesvaras of Varanasi project distinctly a pattern of life and devotion, which was quite contrary to the Vedic. This is also projected by the different sects: the Vaisnavas, the Saivas, the Ganapatyas, the Bhairavas, the Nathas, the Tantrikas. We shall have to meet these sects and their centres later.

These and many other references in the Puranas and Hindu Law treatises obliquely point out to those years of feuds when one kind of social system was being transplanted by another. Stratification of class tiers rose out of the class consciousness of the occupying force who made very determined and organised efforts keeping the vic- tims under serfdom, or even worse.

Thus fought the indigenous denizens, the autochthons of the sub- continent against the inroads of the Aryan menace. The victors tried hard to impose their own gods on those of the victims, e.g., nature and totem gods, like the rivers, the trees, the mountains, the earth, brooks and streams and springs, the souls of the dead, and the fears of a looming mysterious fate.

Be that as it may, the Dravidians, Ganas, or Dasyus, or Raksasas or Yaksas, as we called the autochthons, had their moment of the last laugh. More than eighty per cent of what we observe today as the religious format of the land of the Sindhus (Hindus) is but what we have accepted and adapted from the victims of the victors. Hinduism of today is but a phonetically comprised form of Sindhuism. And when we scratch the skin of Hinduism, the underlying major trends and ritualistic forms remind us of non-Vedic indigenous ob-servances.

V

All through this attrition, Varanasi continued to be where she had been. By the river Ganga, serene and composed, she continued to nestle the tired, protect the harassed, shelter the fugitive, cleanse the ailing and compose the ruffled.

Talk of Venice, Florence, Geneva, or Lucerne, talk of the picture of London as such from the Thames, or New York from the New Jersey heights, or of Edmonton from the other bank of the river,- no riverside township could match Varanasi's beauty and grandeur. Like the Taj amongst the buildings, Venus de Melo amongst the famous marbles, Varanasi's beauty stands out as an experience, a realisation, a sensation for the connoisseur. Wordsworth was justified writing 'Earth has nothing to show more fair' only because he had never seen the fairer Varanasi from the river on a sprouting winter's dawn.

It must take a whole lot of determination and strength of mind to overcome the massive spell that Varanasi could cast, and yet keep one's cool. The lost procession of centuries actually appear to be seeping out of the stones, and towers of the temple minarets. The brass bells knell aloud in waves of ringing echo-es from nowhere. The pilgrim gets wrapped up in a historical and cultural milieu much in the same way as a dilettante tourist would, walking the winding lanes of Rome or of Venice, Florence, or even of the pretty town- ship of Salzburg. Varanasi overwhelms with her prehistory.

The squalor, the rot, age old tradition of trickery and fraud, the time honoured syndrome of priestly greed and beggary, the un- spotted odours, the garish crowds, the festering disowned of the earth, the philosophic bulls and the grinning monkeys, the exhibi- tional python or cobra, the fortune-telling birds, excellent man-ani- mal coexistence within fighting inches of crawling space, all crowd upon the mind, and test and tax the strongest will-force of the most determined of the brave souls. The catch of the place prevents one from seeking a quick retreat to more familiar surroundings, where the suffocating weight of the many dark centuries could be cast away.

Varanasi bemuses with its thrall. One would like to run away from it all, but having run away would again come here to feed a nostalgia which is romantic in its stark realities and realistic in its roman- tic orientalism.

Only the bravest could stand these metamorphic changes in a spinning time-tunnel.

The unexpected mix-up of the familiar-unfamiliar, past-present, history-life shock untrained minds with a whirlwind series of the unheralded, engaged, as it were, in ghostly dances alternating with thrilling divine experiences.

Varanasi is a tourist's challenge, a pilgrim's nerve-wrecker, a poet's pocket book, and a vagabond's paradise. Varanasi is an extension of man's capacity for quick adjustments.

Varanasi is an art album, a museum of oddities, a sanitary inspector's notebook, a gourmets' Elysium.

Varanasi is the ultimate abode of the sick of mind, the engaging companion of the forlorn in spirit-yesam anya gatir nasti tesam Varanasi gatiḥ. Varanasi offers a way to those who are lost to all other ways. Here the absurd attains sublimity, and a savant reaches the coveted point of self-sought stillness.

2

Speaking of Varanasi, are we sure where indeed the city is situated? In fact was Varanasi at all a city? If not, since when it gained that status?

Then, where is Kasi? That too is a crying question. Are Kasi and Varanasi identical? Are they twin cities like Howrah-Calcutta, St. Paul-Minneapolis?

According to the Puranas, and the Jaina-Buddha texts, Kasi and Varanasi appear to be two different places. Varanasi a holy hill was covered with wooded lands, washed by several brooks and streams and embellished by large tanks as well.

Varanasi was the powerful fortified capital of the age-old jana- pada (district) of Kasi-Kosala.

Besides Kasi and Varanasi, we hear of four other descriptive appellations: Anandakanana, Gauripiṭha, Rudravasa and Mahasmasana. Where could these be identified and located?

If the locations are different, then which one of them is earlier? If these are historical realities, then our enquiry is pertinent.

In the Jatakas we come across many more names of Kasi. Of those by and by.

Or could we brush away these names as mere myths?

But even myths are not supposed to be totally unreal or, baseless. What is totally unreal cannot enjoy a lease of life as long as fifty centuries. Myths, according to Graves and Gopinath Kaviraj are camouflaged forms of history, preserved in a colourful symbolic language, for the benefit of educating the mass. Myths serve as a cultural mind-bank for students of sociology.

II

For finding out the ancient site of Varanasi we have to study critically all types of references and artifacts still available to us. We have to investigate the Vedas, the Samhitas, the Jaina-Buddha texts (particularly the Jatakas), the Puranas, the Epics, travellers' reports, leg- ends, and of course a close study of the ruins and monuments still available for scrutiny.

Of course the Varanasi, which had been the holy of holies to hermits, seers and spiritualists, used to be a hilly woodland carefully tucked away from the hurry and heat of life.

It had always been there, known to the indigenous autochthons, i.e., the established pre-Aryan communities, natives to the soil, and generally referred to as Dravidas by anthropologists, and Dasyus, Danavas, Nagas, even Asuras, Yaksas and Raksasas by Vedic literature. These have also been referred to by the omnibus term 'Gana- Naga', as used in the Epics, and the Puranas.

Varanasi was popular to the linga-worshipping Nagas, and Dravidas, locally known as Bharas, Bhandas and Suirs.

All in all the Nagas and Ganas maintained a great regard for Varanasi much before the Aryans had ever heard of it.

The mysterious Aryans [Airayas (Avesta), (Iranian Rock Inscrip- tion)] who could have been very close to the forgotten Hittites of the Asia Minor, moved for whatever reasons towards parts of Asia and Europe. These Indo-Aryan clan-bands moved towards the for- midable Hindukush, and eventually crossed it. The mighty Sindhu shocked and challenged them, and they began to pray to its might. This could have taken place 5500 years back or more. They came in different flocks or hordes: Madras, Parasa-s, Saka-s, Bharata-s, Kasya-s or Kasyapa-s, Vasa-s, Turaba-s, etc., as these were called. They settled in the 'Land of Five Rivers'.

Their date about reaching India has been differently claimed as 3500 BC, 2500 BC.1

They came to settle in the Indus valley, and met a superior culture which seriously challenged their intrusion. By 2500 BC the indigenous culture was superseded by the aggressors. However, they remained for a long time in the valleys of the Sindhu and the Sarasvati, which they eventually crossed (after having reduced that area to a desert because of heavy deforestation, which they had caused, and after seeing the Sarasvati 'hide up' into the sands).

They reached further East until they reached the verdant valleys of Madhyamika or Kusavarta, i.e., the Ganga and the Yamuna, par- ticularly the Sadanira (Gandaki).

Their progress was never unchallenged. The local population, mentioned rather scornfully as Asuras, Dasyus, Danavas, even Raksasas and Yaksas put up great fights. The Rgveda mentions about the superior cultures of these natives

One of the most populated areas, and one dearly loved by the natives was the forested hills of Varanasi on the Ganga. The lovely forests and, orchards (described in the K. Kh.) watered by the rivers Asi, Godavari, Mandakini, Dhutapapa, Kirana and Varana ap- peared to the original inhabitants as a piece of crystallised heaven where they presumably freely practised their native religious adora- tion of Pasupati and the Mother.

The Vedic people, who knew of no Mother, no Purusa-Prakrti syn- drome, called this kind of worship as the Rudra (fierce) way, and termed the mystic hills as Rudravasa, 'the abode of the fierce peo- ple', or Mahasmasana, that is to say, that it was a part of the country, which, because of its weird ways with the dead bodies, was no better than an extensive crematory ground, with Pisacas, Siddhas, Vetalas and Ganas (non-Aryan communities) as its residents.

Rudras have been regarded as anti-Vedics in the Rgueda. But in the Satapatha Brahmana the Rudras are found to be coexisting with the Vedics.

Rudravasa as a name for Varanasi could be a reminder to these events. Similarly the name Mahasmasana referred probably to extensive crematory grounds lying along the hills and the banks, and infested by the Rudras, the meat-loving fierce people, shunned by the Aryans.

That the Vedics and the Rudras continued to indulge in fierce fights has been fully corroborated by narratives in the Vedas as well as in the Puranas. Varanasi maintained and still maintains a stern posture of anti-Vedism by upholding the Rudra ways. It justifies its name Mahasmasana and Rudravasa.

Varanasi certainly appears to be pre-Vedic, and certainly the Aryans came to this haloed spot much in the same manner as they had arrived on the banks of the Ganga. The Aryan acceptance of Varanasi as a holy place appears to have been a much latter event than their acceptance of such places as Naimisaranya, Dvaitavana, Kamyakavana, Puskaravati, the Sarasvati and Kuruksetra.

This was not the case of Varanasi. Records about how it had all started, though covered in half-myths, are rather clear about the foundation of a Kasi-Lunar-dynasty. (It is remarkable, however, that none speaks of Varanasi, as a synonym for Kasi in this context.)

From those pre-Vedic days to the days of the Sharqui sultans of Jaunpur (Jamadagnipuram) [destroyed by Firoz Shah Tughlaq (along with Sravasti), and renamed Jaunpur, in the name of his cousin Jauna, the future Muhammad Tughlaq (1447)], Kasi (not Varanasi) flourished as an important Hindu janapada, or State.

References to Kasi go back to the earliest Veda-Purana documents. Jaina and Buddha records too attach importance to the en- tire Kasi-Kosala region which includes Ayodhya, Dattatreyaksetra (modern Ghazipur), and certainly Markandeya (modern villages of Kaithi and Bhitri near Varanasi), situated near the confluence of the Gomati and the Ganga.

Kasi has been referred to in (a) the Rgveda, (b) Paippalada Sam- hita, (c) Satapatha Brahmana, (d) Brhadaranyaka Upanisad, where Gargi, calls Ajatasatru, king of Kasi and Videha, (e) Sankhayana Srautasutra, where Jața-Jatakarni has been mentioned as a priest of the Kasi kings, (f) Baudhayana Srautasutra which mentions Kasi and Videha as neighbouring places, (g) Gopatha Brahmana which mentions Kasi-Kosaliya, (h) Aitareya Brahmana, which puts KasI much earlier than 1000 BC.

This of course suggests a pre-Vedic existence of Kasi. Varanasi must have been yet a much earlier place, where recluses and her- mits used to meditate, or take formal spiritual classes.

Besides the above references in Vedic literature, Kasi finds significant mention in the Puranas: (a) Bramha Purana; (b) Vayu Purana; (c) Skanda Purana devote special sections on Kasi, Kasikhanda contains valuable informations on Kasi.

From these chronicles we come to know of the foundation of the beginning of the Lunar Princes of Kasi (Manu, Buddha, Pururavas, Kasa). Kasa is supposed to be seven generations away from Pururavas, a Vedic personality.

However sweeping and vague, these references establish the following: (a) Kasa's Kasi was much more ancient than the Epics and the Puranas. An earlier city could have been renamed by Kasa in his name, much as other princes have renamed cities, e.g., Allahabad, Daranagar, Aurangabad, Ganganagar, etc. (b) The presence of a township between the Ganga-Varana confluence in the south, and the Ganga-Gomati confluence in the north was a fact which takes us further back from the times of the Aryan push. (c) After this we come to the sumptuous times of the great Epics where Kasi-Varanasi has been eloquently described again and again, the two names of- ten losing their individual distinctions. Kasiraja was regarded as a powerful ally by all the rulers of the times.

The fixing precise dates of the Puranas, in spite of hard labours of scholars, has remained elusive. But discriminating investigators take the period to be between the times of the Vedic Aranyakas, and Gautama Buddha. Some of the Puranas show signs of the period of later Muslim intrusions. (These would have been composed between fourth and twelfth centuries AD.)

This investigative conclusion is based on certain facts. Antiquities of the Puranas have been traced to some of the Vedic texts.* of course Kasi-Varanasi has been mentioned 'together' as an important janapada-nagari both in the Manusmrti and in the Mahabharata. Evidences like these could not be neglected in this context. Puranas are important documents. Chandogya calls the Puranas as the Fifth Veda, and Smrti accepts them as popular com- mentaries on Vedic truths. Poet Banabhatta of Kashmir (seventeenth century AD) mentions the Puranas with due respect.

Thus we see that in considering the antiquities of Varanasi Puranas provide important informations. So do the Jatakas, which are filled with references to both Kasi and Varanasi, which is called Isipattana or Rsipattana. Another Buddhist text, Dhammapada Attakatha mentions Varanasi-Isipattana as different from Mrgadava-Sarnath. This is a notable information for our research.

Finally, we have the records left by pilgrims and travellers. Fa- Hien, Hiüen Tsang, both Chinese, Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador at the court of Chandragupta Maurya, and Al-Biruni, the great Islamic savant, all have mentioned Kasi and Kosala as different places. So does the Arthasastra of Kautilya.

IV

Kasi the city was completely destroyed by wars and feuds of religious bigotry. After the devastation caused by Muhammad Ghori (1194) and Qutbuddin Aibak, Kanauj and Kasi had become a lost memory.

But the trading interests of towns like Kanauj and Kasi forced the business community to shift for other suitable centres, close to the former areas of operation. Thus between Varanasi, Kasi and Kanauj various smaller villages grew up as scattered centres for trade. These trade centres gave rise to small townships, which dot all the way between Varanasi and Ghazipur, keeping always close to the Ganga.

This lost Kasi has now become the subject matter for scholarly investigations, and a point of curiosity to antiquity hunters.

In course of time their efforts succeeded, their greatest achieve- ment being the marvellous discovery of Mrgadava-Sarnath which lies partially discovered. But much of the environs still call for continued efforts. A heavy, blanket of dusty silence covers untold number of precious mines which store further knowledge about the lost Kasi.

Rediscovery of ancient Kasi has been rendered difficult by continuous destruction spreading over a long period. What took 1600 years to loot and destroy (500 BC to AD 1100) must take a long and persistent organisational effort to reveal and reset. Discovery of Kasi has not been started yet.

The rediscovery of Varanasi, which is supposed to be a living city, has not become easier through periodical destructions suffered in more recent times. Such destructions are generally ascribed to the Islamic foreigners alone; but the greatest factor that completely had upset, and obliterated the very layout of Varanasi beyond any recognition, has to be clearly named. This is the English factor.

Indeed so persistent has been the sad and mindless destruction, that the ancient woodland, famed for its sages, scholars and hermits finally disintegrated. Most of the important shrines and ashramas sought safer places to hide. Many of the former revered deities, mentioned in the scriptures, were moved to hideouts too.

The temple of Visvanatha attracted the special wrath of the iconoclasts. It was situated on the highest point of the township, and its wealth offered a tempting loot.

This temple was time and again demolished, as it was reconstructed again and again. The temple of Visvanatha had become a battle-ground between forces of destruction and the stubbornness of the pious.

It had a history of its own.

Nearly about 1018 the city of Kanauj (Kanyakubja), the most prosperous glittering city of Asia of its time, was razed to the ground by the forces of Mahmud Ghazni. Since then the destruction and pil- lage of Hindu, Jain and Buddhist temples became a regularity with the invaders. Under the pretext of religion the sack of Hindu temples meant for them, money, power and land benefits. Even monasteries and schools did not escape the zeal of the invaders.

V

A tragic side-effect of these destructions was the problem of forced conversions. At the beginning the convert nursed a keen desire for a come back to his fold, and for acceptance by their relatives and friends.

But this did not happen at all.

Apart from scriptural objections against conversions in general, the Hindus could not either (a) convert Muslims into the Hindu faith, or (b) re-convert their converted cousins and relatives back into their fold, on pain of death. Further, more no Hindu could marry a Muslim into his faith, and such marriages had to be functioned on pain of death under Islamic shari'at.

The laws left practically no choice to the Hindus. Once converted, they stayed converted.

The converts, incensed by the unfair scorn of their cousins, and cruel rejection by their ancestral society, grew into a band of yet more determined destroyers, inclusive of holy sites. In breaking the temples, actually they tried to tear the harsh purist social fabric to pieces. These were their own people who could have managed to show them reasonable consideration, in spite of the laws. They expected a sympathetic community life, which was, surprisingly and shockingly, denied to them.

The existing communal tension in the subcontinent is traceable to this fratricidal tension built up between Indians and Indians. Later foreigners had to play little part in it, except to nurse it, and fan it for their economic and political gain. The suicidal trend, unfortunately, has not stopped since.

This fact is observed by closely following a social pattern. It points out to a special nature of population distribution in various unsettled settlements of Varanasi. It seems quite remarkable that in Varanasi of today, in and around the ancient holy sites, where large scale destruction had once taken place, colonies after colonies of the early converts, the rejects of a proud and stern society, still struggle together for an existence which had been forced upon them by agents of social tyranny. They still manage to live side by side with a mixture of the local Hindus, who traditionally had been their erstwhile cousins.

Today they eke out a sparse living as they did in the remote past by carrying on their ancestral trades and industries. Most of them belonged to the manufacturing guilds once-famed throughout the civilized world from China to Rome for their fine handicrafts. Although pushed aside by their erstwhile brothers into separate pock- ets of society, they still carry on their traditional trades and occupa- tion. They still manufacture articles from silk, cotton, brass, ivory, bronze, gold, silver, copper, wood, even cane, grass and lacquer. It is remarkable that most of the stone and marble images of Hindu deities are the handiwork of these converted Muslim sculptors.

From times immemorial Kasi traders and Varanasi craftsmen have been the traditional builders of a special social elan which has remained unchanged in spite of changes of religious loyalties.

To usurp and encroach upon lands belonging to the temples, and then build for free accommodation gradually, has become synonymous with the automatic rights of the forced converts. For, the defeated, in their remorse and fear, not only kept away from the temples, but also abandoned rights on the attached lands. They abandoned the rights of even raising their voice against vandalisation of the beautiful carved stone artifacts which were freely carried away, and used for embellishment of private and public properties like mosques and palaces.

Nonetheless, the convert artisans still hug on to these areas which were rendered vacant after the devastating sack forced upon them by hurricane assaults which eroded their social identity.

Such turns and twists in history have inevitably left scars on the lives of the people. Failing to turn elsewhere, they found it safer to settle wherever they could, and grab for themselves a little living space snatched from the absent and cold Hindus.

Acts such as demolishing places of worship for collection of ma- terials for building new ones; filling holy tanks for reclaiming a few acres of land for housing, squatting, encroaching, ravaging, appear to have become almost traditional preoccupations for these colonies of zealous converts. They stake their claims on the lands of the ruined temples as their legitimate war property, and often put up old documents signed by the then rulers as their title to the ac- quired battle gifts. Many of the claims rested on their legal deeds held before they had been converted. Most of the Muslims in Varanasi actually enjoy ancestral rights over property.

Such uncontrolled forces of demolition and reconstruction have not been of much assistance to scholars who are in search of the old Varanasi and its religious environments.

But as a community, the Muslims of Varanasi by themselves have been quite liberal in accepting the moral values of their age-old social environs. They find it a pleasure to display their Islamic brotherhood and hospitality, and live in the best of relations with their neighbours.

A deeper look into any of the Muslim neighbourhoods of Hindu Varanasi reveals the pleasant truth that the communities live in a close compact, almost cheek by jowl, each extending camaraderia to protect the interest of the other, although they maintain meticulously their divide of religious and social norms.

A tradition of respect for different communities is a precious heritage that still characterises the behaviour of the people of Oudh, ancient Kasi-Kosala. Muslim rulers of Lucknow, Rampur, Jaunpur have been, by and large, examples of accommodation of this social spirit.

VI

Not the Buddhist, not the Muslims, not even the atrocities of the foreign conquerors have been responsible for eroding the ancient esprit de corps of the Kasi-milieu. No catastrophe had affected the ancient character of Varanasi so radically as did the few sad and negative years of the proud imperious alien English. Insularity was a synonym for survival for these islanders. Intolerance and arrogance provided for them a stance for effective loot in the name of administration.

They plundered the most, rifled the most, carried the fortune away to build their society across the seas by draining the resources of India. But they did it so deftly under the protective excuse of their laws that they escaped successfully any indictment in a court of law. It was a case of legal brigandage unique in the history of the world.

They missed the continental spirit, and fared miserably in com- prehending the sensitive acceptive catholic mores of a continental people. The typical English mind was incapable of evaluating, com- prehending and assimilating the diverse ways in which the medley of the people of this largest continent, especially of the people of the Indian subcontinent, lived in the harmony of the human spirit.

Because India proved to be too big for their schemy manage- ment, like dogs and lions managing large hunks off a carcass, they decided to tear up a great people to convenient sizes and swallow the whole thing in their own good time. The dogs did as much as the lions did, but always legally. Law of course is an ass.

Asia, the cradle of civilisation and culture, had always lived with the many, with workable understanding and a spirit of coexistence. But this spirit was quite foreign to the British passion for swift ag- grandisement and clever exploitation. Victimisation through humili- ating the conquered, and an incorrigible passion for glory and power, permanently alienated a group of erstwhile welcome merchants.

Whereas the destruction caused by Islam in Varanasi was inspired by human cupidity and religious bigotry, the havoc caused by the English was the result of a deep and damning imperial scorn that the arrogant always nurse against their victims and serfs. Prompted by an avaricious greed, these land-pirates carried on their nefarious activities in the name of a good and stable government.

The freedom and democracy that they boasted of was a thing meant for their island-community. As rulers of the darkish Asians, they encouraged a policy of divide and rule, tear and swallow, cleverly disguised under a masque of high justice. They lived by a show of scorn, insolence and swagger. Scourges like the Hunas, Taimur, Mahmud, Nadir or Abdali are but bad dreams of history. They came like midnight. They left with a new sunrise. But these (Hyder Ali called them 'rats') never left, until they were forced to.

Whereas the Islamic rulers of Lucknow left on their subjects the tradition of neighbourliness, art and liberalism, the rulers from the British isles have left to India the dismal heritage of communal dis- harmony, riots and mutual sectarian mistrust.

Indian history never before the British knew of communal riots. In spite of that poison, Varanasi and its mixed society still maintains its social calm, which is as placid and sedate as the blue cur- rents of the quiet Ganga, as firm and solid as the rocks on which the ancient retreat of Anandakanana, and the present city of Varanasi still rest.

VII

The defeat of Warren Hastings at the hands of Chet Singh (1781), the ruler of Varanasi, provoked the white aggressor, who, as be- comes a genuine upstart, was entirely incapable of comprehending the mores of the scion of an ancient royal house. The whiteman's defeat at the hands of what he considered to be a native princeling, a mere feudal chief, hurt his arrogant vanity. The spell of British invincibility was rudely shaken at the clumsy hands of a native.

With the help of some ill-advised poor quislings he made his second attempt, and finally succeeded. Though Varanasi was finally humiliated and raped, yet the earlier defeat, like a constant barb, made Hastings deal with the town in a manner which the people of today cannot even comprehend.

The final destruction of Varanasi by the English was carried on through the helping hands of 'expert' foreign engineers and town- builders with little or no knowledge of handling antiquities, history and honoured sites of an ancient seat of learning.

Indian antiquities to them, any way, were of less importance than the stones and slabs of Westminster, or of Worcester, or Tintern churches.

Whereas the Muslims had a deeper appreciation of the Hindu norms (since these were in fact, but the erstwhile Hindus converted to another faith) being people of the same land, origin and blood, the Christian rulers in contrast, found no reason at all to respect the holy monuments, the sacred baths, the seats of learning, the wooded hermitages. The quiet and beautifying rivers that flowed through the famous woodland of Varanasi were deliberately choked and flattened to provide broad access for the 'sightseers' to the riverside, so that Europeans could travel 'safely and comfortably' un- der liveried protection on wheeled carriages.

No, not the Buddhist zeal, not the Muslim bigotry, not the molestation of Tartars and Kusanas, not the rapacity of the plunderers, Varanasi was 'not' destroyed by any of these factors: Varanasi was destroyed by the calculated mischief and erratic town-planning of English administration.

Varanasi was destroyed by the perfidy of the self-serving imperial myopic agents of Great Britain, representing the economic stranglehold of the East India Company, particularly by its vainglorious agents like Warren Hastings, Clive, Vansitart, Barlow, Impey particularly by Warren Hastings, whose pride had been hurt by a 'mere' native prince, Chet Singh.

That imperialistic contempt eroded Varanasi's ethos and individuality. Today Varanasi is not even a ghost of the ancient Ananda- kananam. The entire psyche had quailed under a repressive alien heartless administration. The legendary township was suffering from a metamorphic trauma.

That real Varanasi was gone. Hence the question of its rediscovery. It is a civic and moral responsibility for every student of history and culture to try to see and feel the Varanasi that was, and is no more.

The so called benign rule of the islanders had completely changed the topography and panorama of the wooded hills on which rested the pre-Vedic holy woodland of Rudravasa and Anandakananam, the abode of Siva and Saivism.

That was the Varanasi of Kasikhanda, Agni Purana, Vayu Purana, the Mahabharata, the Jatakas, and of the records of Hiuen Tsang, Fa-Hien, Al-Biruni and of the ancient poets who have been singing about its glories.

But that Rudravasa is no more. It has been overrun the lost city of Varanasi. Forced by continuous ravages Rudravasa was forced to seek shelter under a new name, Varanasi, which still maintained the smooth spirit of Anandakananam.

Much like refugees seeking shelter elsewhere after their total loss, the Kasi refugees stuck to the body of Varanasi, which by scriptural injunctions had been reserved as a place 'out of bound' for the householders. The tranquil calm that was the special attraction of Anandakananam was soon exploded, and a struggling mass took over whatever space was available to them. The entire Varana-Rajghat front was urbanised up to the slopes of the Visvanatha hill and Jnanavapi. The ancient face of Varanasi was undergoing a deep change.

The soul of Anandakananam suffered from a debasement of the inner spirit.

For whatever reasons, half political, half ignorant, half philosophic cynicism, the city fathers of today turn a Nelson's eye to these gradual destructions, or to the crying needs of putting a halt to the vandal- ism, and start retrieving a past, and reconstructing a future.

Varanasi, the oldest city on earth, famed for its quiet and spiritual élan, for its ashramas, hermitages, retreats, meditation centres, schools, hospitals,-Varanasi, known for its ponds, lakes, rivers and rocks, is still being dishonoured, raped and disfigured. Varanasi has been reduced to an overcrowded market-place, where the devout is just indulged because the civic panthers cannot do without their sweat-soaked coppers, which pour and pour as devotional offerings from all over India.

The City-fathers appear to have decided to let Varanasi take the way of the lost cities of Nineveh, Tyre, Taksasila and Nalanda. The present Varanasi has been losing its solid and special char- acter through continuous streams of refugees, and fraudulent political bunglings. The new rush from the displaced rural population as well as from the onrushing factory workers, and above all, from, the steady visits of pilgrims and sightseers has not helped much to keep Varanasi quiet and clean.

Expansion of modern facilities for communication has been work- ing against the interests of Varanasi, and against the preservation of its individuality. That legendary peace for which Anandakananam was famed, has fled, and in its place prevails blind orthodoxy and mean cupidity.

Ancient Varanasi's bloated body, still, however, keeps floating on the sea of Time, unrecognisable, but still the body of the venerated past.

But it is a greater tragedy that the spirit of Varanasi has long since evaporated, leaving behind a mutilated carcass.

Today Kasi-Varanasi of old has encroached upon the older Anandakananam. Although Varanasi has retrieved her ancient name, after the Indian Independence, from the corrupted appellation of Banaras, yet she has lost her essence, her spirit. Rudravasa is a distant echo, Anandakananam a mere dream.

The ancient woodland is gone; the urban Varanasi has taken over,

and a busy city carries on its hectic commerce where sages used to come for peace, and anchorites for meditation.

Neither Kasi, nor Varanasi lives up to its ancient form and glory. This is perhaps as it should be. There is an inscrutable law of life that old order of things must give way to the rolling wheels of Time. Under Time's wheels all vaunt is grist. Things which had been, must eventually become the things that never again would be. Though regrettable, this is indeed inevitable. No mortal structure could boast of standing up to Time. By the immutable law of physical mutability Varanasi too must go the way of all flesh, and disintegrate.

VIII

Kasi had gone to the dusts centuries back. Old Sanskrit records are filled with the chronicles of these destruction. Under continuous thrashings of the times of Nikumbha, Ksemaka, Divodasa, Pratardana I, Pratardana II, Ajatasatru, Prasenjit and others, under the pressures built up through the protracted feuds of the Ganas and the Vaisnavas, the Rudriyas and the Kapalikas, ancient Varanasi had been deeply molested and scarred.

K. Kh. clearly chronicles these feuds, which are confirmed by conventional history books. Whereas these feuds could be described as the results of aggressiveness of one culture over another, one form of religious belief on another, in historical times the feuds have been turned to political battles. These are still being carried on. From the time of Bhisma, who fought with Kasiraja, to the times of Ajatasatru, Prasenjit, the houses of Pratardana, Haihayas, Satavahanas and Gahadavalas, Kasi has always been occupying the centre of Bharatiya history.

The Islamic invasions came much later. In fact Kasi's safety was exposed to foreign aggressors specially after the defection of Jaipal of Kasi under the forces of Qutbuddin, a general of Shahabuddin Ghori (1194) of Kabul.

James Prinsep refers to some Islamic records which casually mentions that Kasi was being ruled by a prince named Bonar, who was defeated by Mahmud Ghazni in 1117.

By that time Varanasi had already changed its location, so had Kasi. Of the most ancient of the monuments of that ancient Kasi, Sarnath alone stands as a reminder

3

Who had really destroyed Sarnath? One fanatic sect at one time, or many such at many times? It is a highly controversial point. Sarnath and its environs now stand deserted. The ruins present us with evidence stretching from 500 BC to the end of the twelfth century. About 600 BC Hiuen Tsang had found it intact. Kumaradevi, a princess of the Licchavi clan, and Queen of King Govindacandra Gahadavala of Varanasi (a very powerful and accomplished ruler of his clan) had embellished it by her gifts.

Who then brought about the disaster? It must have happened (a) after 600 BC, and (b) through non-political motives. Was it due to religious bigotry? But it could not have been Islamic. Who then or what was responsible for the catastrophe?

Any way, the disaster did not come in a day, in a year, in many years. It must have come much before the Islamic disaffection. In fact at the peak of the cataclysmic raid of the foreigners Sarnath had already been turned into a ghost habitation, where, according to rumours, only devils and demons kept their nocturnal dances.

Not unlikely, the place had been infested with weird followers of the Vajrayana and Paisaca rites, and the simple folks were likely to believe in tales carried by villagers of the strange happenings around the once holy quiet place.

The ghoulish tale nothwithstanding none could stop the villagers far and wide to carry away rich hauls of building materials scattered all over and around the abandoned ruins. The material helped them to build their own houses. Even the more well to do could not resist the uses of those broad bricks and polished stones, often even items of beautiful sculpture, to bedeck their buildings.

The ruination must have started at the times of those wars of attrition between the Haihayas of the south, and the Pratiharas of the north. Scholars also think that the Bharasivas of Rudravasa were partially responsible for the demolition of Sarnath. Of course they had enough provocation to do so.

To their untrained and unaccustomed eyes the abominable Vajrayana degenerations (like animals sacrifices with free use of liquors, promiscuity, prayers in semi-nude or even nude state of male and female partners, interfering with dead bodies and suspected human sacrifice) had overwhelmed the holy viharas. Even the sacred precincts of the sangharamas (monasteries and nunneries) were not spared. These last, they thought were not better than clever traps set for spoilation of their youths and their homes. The anger of the untrained brute could easily start a devastating conflagration leading to total destruction.

This was precisely what must have happened to the holy vihara of Sarnath.

In this connection the contribution of the powerful Gahadavala royal benefactor, Kumaradevi's role was very important. The poor Queen, probably of Mongoloid extraction, being a princess of the Licchavi clan, was understandably swept away by Tibetan Vajrayana charms, which got not a little incentive from the degeneration of the Jainas who preferred to remain in the nude (Nagnikas and Nirgranthis).

The Sungas (c. 187-30 BC) and the Satavahanas (c. 30 BC-c. third century AD) contributed to the glories of Sarnath. In a way though Brahmanically disposed, the Gahadavalas too contributed substantially to Sarnath. Their contributions were chiefly inspired by their weakness for Tantra and Tantric rites. In fact they established a number of Tantric Vajrayana deities in Sarnath like Vaisravana, Vajravarahi, Marici, Vasundhara etc.

Excavations have exposed a secret subterranean pathway lead- ing to the nunnery of Kumaradevi, which raises sinister suspicions about its uses. R.D. Banerji has boldly suggested that the pathway was a secret device to allow male participants of the séances to reach the nunnery without being detected. Naturally gossip spread, and tempers flew.

The great age of Amitabha Buddha had given way to those obnoxious rites. This irked the residents of Varanasi, who still adored the sermons of the Great Teacher Sasta.

King Govindacandra's reign came to an end by 1154. Deprived of his controlling power, things ran from bad to worse.