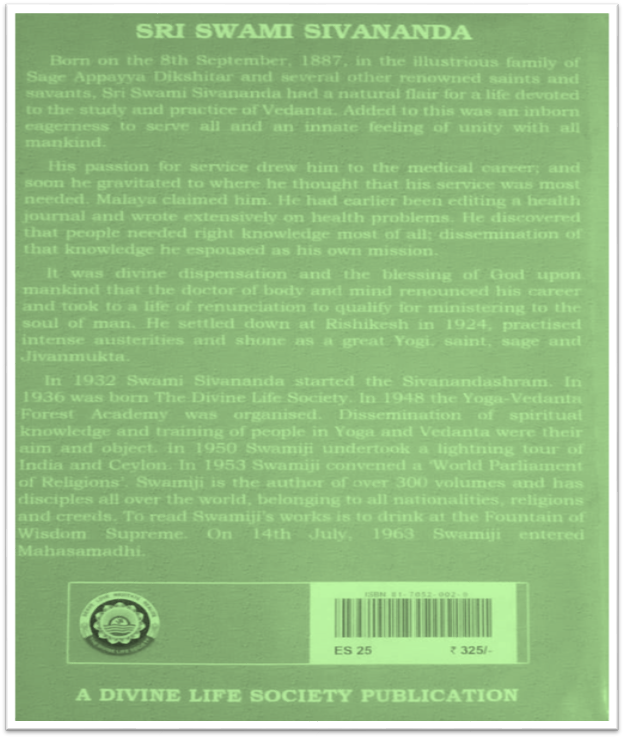

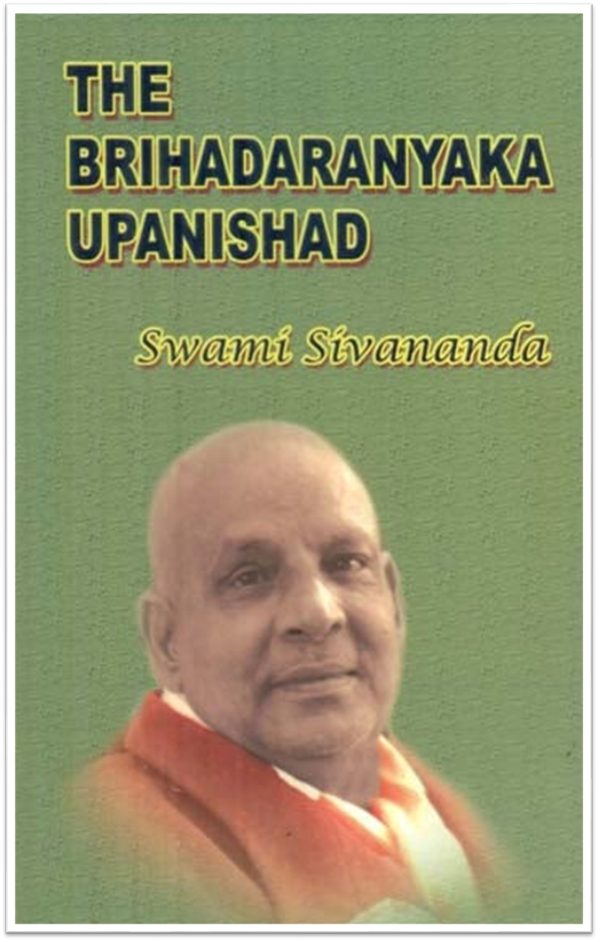

THE BRIHADARANYAKA UPANISHAD

SANSKRIT TEXT, ENGLISH TRANSLATION

AND COMMENTARY BY

SWAMI SIVANANDA

Published by

THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY

P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR-249 192

Tehri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand, Himalayas, India www.sivanandaonline.org, www.dlshq.org

First Edition: 1985

Second Edition: 2000

Third Edition: 2017

[ 1,000 Copies ]

The Divine Life Trust Society

ISBN 81-7052-002-9

ES 25

PRICE: 325/-

Published by Swami Padmanabhananda for The Divine Life Society, Shivanandanagar, and printed by him at the Yoga Vedanta Forest Academy Press, P.O. Shivanandanagar, Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand, Himalayas, India

For online orders and Catalogue visit: dlsbooks.org

Table of Contents

Satya-Brahma-Samsthana-Brahmana

Worshipful H.H. Sri Swami Sivanandaji Maharaj could see through the publication of his translation and commentary on the eight Upanishads,–Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna,, Mundaka, Mandukya, Taittiriya, Aitareya,–during his physical presence in this world. But as an ardent and devout follower of ancient tradition, he was also aware and was particular that the major Upanishads, which form the philosophical foundation of spiritual culture, ten in number, should all be presented and brought out for the benefit of seekers of Truth. For various reasons, it did not become possible to bring out the remaining two Upanishads, viz., the Brihadaranyaka and the Chhandogya, the largest ones among the whole group; and Sri Gurudev did, once or twice, hint at the Management of the Divine Life Society about the necessity to bring out the Commentaries on the remaining two Upanishads also. The circumstances at that time were somehow such that this publication did not see the light of day during his lifetime. But his disciples and devotees were acutely conscious of the wish of the great Master, which they were eager to fulfil at the earliest available opportunity.

Thus, we release this pleasant and stimulating surprise to the public, this large edition of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, may we call it a magnum opus–with the original Sanskrit text and an English translation of the same, together with an elaborate expository commentary. The first edition of this book was published in the year 1985. As there is consistent demand from the reading public, we are bringing out this edition.

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad is the most detailed and magnificent revelation of the ancient philosopher-seers, which, in its six chapters packed with thought and revelation, provides to the students a practically exhaustive and concentrated teaching on every aspect of life, making it an indispensable guidebook to the student of literature as well as the philosopher, the religious devotee, and the mystical and spiritual seeker engaged in meditation for divine realisation.

The holy corpus of the Veda, which is the repository of eternal knowledge and wisdom, is divided into four Books, known as Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda and Atharvaveda. In each of the four Vedas a distinction, has been made according to content and form: (1) Samhita; (2) Brahmana; (3) Aranyaka; (4) Upanishad.

The Samhita is a collection of hymns or prayers, to God in various Manifestations, containing also formulae necessary in the sacrificial use of these hymns, known as Mantras. On a practical basis, the Samhita is to be considered as the chief Veda, and it is the Samhita that people have in their minds mostly when they refer to the Vedas, the study of the Vedas, the greatness of the Vedas, or holding the Vedas as the foundation of India’s spiritual and religious outlook of life. The Mantras are addressed to divinities, Devas, as the infinite forms of the Supreme Being, these forms of divinities being regarded as the gradational accessible approaches to the Creator by the corresponding levels of evolution and comprehension of the worshipper, the devotee, or the seeker.

The word ‘Samhita’ means a collection of the Mantras belonging to a particular section of the Veda, which are either in metrical verses (Rik) or sentences in prose (Yajus) or chants (Sama). The Rigveda Samhita consists of 10580 Mantras or metrical verses; the Samaveda Samhita contains 1549 verses (with certain repetitions the number is 1810) many of which are culled from the Rigveda Samhita. The Sama hymns are modulated in numerous ways for the purpose of singing during either prayer or sacrifice. The Yajurveda Samhita consists of two recensions known as the Krishna (black) and the Shukla (white), and consists of prose sentences and long verses. The Atharvaveda Samhita, while it is included among the four sections of the Veda, is generally not studied as a prayer book and is used only during certain specific forms of sacrifice and also for incantations of different kinds to receive benefits to the reciter, both material and spiritual.

The Brahmanas teach the practical use of the verses and the chants presented in the Samhitas. However, the Brahmanas, though they are supposed to be only sacrificial injunctions for purpose of ritualistic utilisation of the Mantras of the Samhita, go beyond this restricted definition and contain much more material, such as Vidhi (a directive precept), Arthavada (laudatory or eulogising explanation), and Upanishad, (the philosophical or mystical import of the chant or the performance).

The Aranyakas are esoteric considerations of the practical ritual, which is otherwise the main subject of the Brahmana. The opening passage of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, in which the horse-sacrifice is treated as a symbol, would serve as an example of how a ritualistic symbol and material is used as a cosmological concept for purpose of religious contemplation and philosophic meditation. The Panchagni-Vidya of the Chhandogya Upanishad may also be cited as an illustration of a cosmological or astronomical and physical event being taken as a spiritualised symbol for mystical contemplation.

The Upanishads, except the Isavasya, which occurs in the Samhita portion of the Yajurveda, occur as the concluding mystical import and philosophical suggestiveness of some Brahmana or the other. The philosophical sections of the Brahmanas and Aranyakas are usually detached for the purpose of study, and go by the name of Upanishads, brought together from the different Vedas to form a single whole, though it appears that originally each school of the Veda had its own specialised ritual textbook with an exegesis or practical manual. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad belongs to the Shukla-Yajurveda group and is the most elaborate of them all, touching on almost every issue relevant to human life, and rising to such heights of philosophic genius as may rightly be considered as the greatest achievement of the human mind in history.

There is also a tradition that the Brahmacharin, or the celibate student (which is the first part of the dedication of human life) occupies himself with a study of the Samhita; the Grihastha, or the householder (which is the second part of the dedication of life) is expected to diligently perform the rituals detailed in the Brahmanas in relation to their corresponding Mantras from the Samhitas. The Vanaprastha, or the recluse, the hermit (the third part of the dedication of life) rises above prayer as a chant and performance as a ritual, and busies himself with pure inward contemplation of the more philosophical and abstract realities hidden behind the outward concepts of divinity and the external performances of ritual. The Sannyasin, or the spiritually illumined renunciate (the fourth and concluding part of the dedicated life) occupies himself with direct meditations as prescribed in the Upanishads, whose outlook of life transcends all-empirical forms, outward relations, nay, space and time itself.

ॐ

ॐ । पूर्णमदः पूर्णमिदं पूर्णात्पूर्णमुदच्यते ।

पूर्णस्य पूर्णमादाय पूर्णमेवावशिष्यते ॥

ॐ शांतिः शांतिः शांतिः ॥

OM. That (Absolute) is infinite, this (universe) is infinite. (This) infinite emanates from the infinite, (the Absolute). Taking the infinitude of the infinite (universe), the infinite (Absolute) alone remains. Om Peace! Peace! Peace!

This is the santi mantra, peace-chant, for not only this Upanishad, but also for other Upanishsads belonging to the same Branch of the veda as the Brihadaranyaka viz., sukla yajurveda. It is a custom which is followed even today, to recite the particular santi mantra at the beginning and end of the svadhyaya of any Upanishad or any portion of the veda. This peace-chant is generally in the form of a prayer to the Supreme about whom the Upanishad instructs, to ward off all obstacles in the path of grasping the import of the teachings. The present mantra is a unique one, as it has, within the short span of a single and simple verse, condensed the whole content of the Upanishadic philosophy. The supreme Absolute is infinite, says this verse. It is beyond the reach of the frail individual intellect of man. It also says that this universe that we see has come out of the Supreme and it is also infinite in its real nature. Thus, the cause and effect are infinite. But there cannot be two infinities. Therefore, the verse says that taking the infinitude of the infinite, i.e., by removing the apparent otherness of the universe through reasoning by the purified intellect, the otherness which is caused by nescience, what remains is the infinite Absolute alone. In other words, this universe is phenomenal. It has pragmatic reality which is transcended by the Absolute Reality which is the real nature of the world and one's own Self. This knowledge is the Saving Knowledge which frees one from the entanglements and sufferings of this world. By chanting this verse one's mind becomes attuned to the Absolute which is non-different from oneself. For further explanation of this verse, the reader is referred to mantra V-i-1. The word 'Peace' which is the shortened form of 'may peace be unto us' is repeated thrice. The first utterance of the word frees us from all pains caused by oneself, the second utterance frees us from all miseries caused by the external world, and the third from all calamities brought about by the divine forces of nature.

SECTION I

OM. Salutations and prostrations to the Supreme who resides in the hearts of all beings, sentient and insentient, who controls the whole universe, who manifests Himself as the universe and yet remains transcending everything, the particular and the universal.

The discriminating mind will find that this phenomenal world is controlled by two broad principles. One is the mystical principle beyond the grasp of the senses and the intellect, and therefore, considered sacred and secret. It is the mysterious divine law. And the other is its counterpart which is the external principle, graspable by the mind and intellect and fit to be communicated to the vast majority of the general public. The former is suitable only to the select few whose minds are of introverted nature. The latter regulates human conduct in all walks of life, in all secular activities including the religious. This external principle is based on the divine one which, though remains invisible and impersonal, can explain rationally all our actions in this world. The latter is unchanging, being eternal, unlike the former which is changing according to place, time and circumstance. As long as we are caught up in the current of the ever-changing world and continue to move with it, we will not be able to know the nature of the divine principle. When once we are able to stand apart as a witness of the world-process, we can know what this great mysterious principle is, and how it is at the back of everything that happens in the external world and the internal mind. How can we come out of the current of this universe and stand apart? This can be done by understanding the real nature of this world which reflects the divine principle in every condition, stage and circumstance of life. So, it becomes possible to know the divine through the world, even as the original can be known through its reflection. The conditioned phenomena can be transcended and the unconditioned Noumenon can be reached through meditation and enquiry. This is the theme of the whole Upanishad.

ॐ । उषा वा अश्वस्य मेध्यस्य शिरः । सूर्यश्चक्षुः, वातः प्राणः, व्यात्तमग्निर्वैश्वानरः संवत्सर आत्माश्वस्य मेध्यस्य । द्यौ पृष्ठम्, अन्तरिक्षमुदरम्, पृथिवी पाजस्यम्, दिशः पार्श्वे, अवान्तरदिशः पर्शवः, ऋतवोऽङ्गानि, मासाश्चार्धमासाश्च पर्वाणि, अहोरात्राणि प्रतिष्ठाः, नक्षत्राण्यस्थीनि, नभो मांसानि । ऊवध्यं सिकता; सिन्धवो गुदा, यकृच्च क्लोमानश्च पर्वताः, औषधयश्च वनस्पतयश्च लोमानि, उद्यन् पूर्वार्धः निम्लोचञ्जघनार्थ, यद्विजृम्भते तद्विद्योतते, यद्विधूनुते तत्स्तनयति, यन्मेहति तद्वर्षति वागेवास्य वाक् ॥१ ॥

1. OM. The dawn verily is the head of the sacrificial horse. The sun is the eye, the air is the breath or vital force, the fire vaisvanara is the open mouth, and the year is the body of the sacrificial horse. The heaven is the back, the sky is the belly, the earth is the hoof, the directions are the sides, the intermediate quarters are the ribs, the seasons are the limbs, the months and fortnights are the joints, the days and nights are the feet, the stars are the bones and the clouds are the flesh (of the sacrificial horse). The sands are the half-digested food, the rivers are the blood-vessels, the mountains are the liver and spleen, the herbs and trees are the hairs, the ascending sun is the forepart, the descending sun is the hind part, the lightning is yawning, thunder is the shaking of the body, raining is making water, and sound is its neighing.

The first section of the first chapter of the Upanishad deals with the meditation on the great asvamedha yaga, the horse-sacrifice. Though this sacrifice is a ritual as other sacrifices are, here it is given for the purpose of meditation.

One who meditates on the horse-sacrifice in his mind gets the same benefit as the one who actually performs the ritualistic sacrifice. The meditation is based on similarities between the symbol on which one meditates, which is here the sacrificial horse, and the object of meditation which is the virat purusha in the form of this universe. Through this meditation, the horse is deified into the virat-purusha. Time, worlds, directions, gods, etc. which are parts of the universe are superimposed on the various parts or limbs of the horse. The mantra enumerates twenty-five limbs of the sacrificial horse, which are to be meditated upon as identical with twenty-five corresponding limbs or parts of the universe, and not vice versa.

The head of the sacrificial horse is to be meditated as the dawn, the period of about forty-five minutes just preceding the sun rise. The similarity between the head of the horse and the dawn, is the importance which both have in their respective fields. The head is the most important part of the horse, and so is the dawn the most prominent part of the day, the brahma-muhurta. Similarly, the eye of the sacrificial horse is to be meditated as the sun, because of two reasons. One is that the sun is the presiding deity of the eye. The second reason is their similarity in that the sun rises just after the dawn and the eye comes just after the head. The vital force of the horse corresponds to the atmospheric air, because the breath of the horse, which functions due to the vital force, is of the nature of air. Based on this similarity, the vital force in the horse is to be identified, through meditation, with air. The mouth of the horse is to be meditated as the vaisvanara-agni, because the latter is the presiding deity of the former. The body of the sacrificial horse is the year. The word 'Atman' in this context occurring in the mantra means the body. The year consisting of twelve months, three hundred and sixty five days and their further subdivisions such as hours, minutes and seconds, may be considered as the body of which these divisions of time are limbs. This is the similarity for meditation. The back portion of the horse is to be identified with the heaven, through meditation, as both are high. The belly of the horse is the sky, both being hollow. Its hoof is the earth, as both are hard. The two sides of the horse are to be contemplated as the four quarters, north, east, south and west, as the former are in contact with the latter. Its ribs are the intermediate quarters, the north-east, south-east, south-west and north-west. The similarity here may be that both are placed in between-the intermediate quarters in between the main quarters and the ribs in between the two sides of the body. The limbs are similar to the seasons, as both are divisions of time, as the body has already been identified with the year. Therefore, the former should be meditated upon as identical with the latter. The joints of the horse are the months and fortnights, their similarity being the connecting link, the former connecting the parts of the body and the latter connecting those of time. The feet of the horse are to be meditated upon as the days and nights. The similarity that helps meditation here is that even as the horse stands on its feet, the presiding deity of time stands on days and nights. The bones are the stars, because both are white in colour. The flesh of the horse is to be identified with the clouds. The likeness here is that even as blood drops from the flesh, water drops from the clouds. The half-digested food is the sand, as both have unconnected and loose parts. The blood vessels of the sacrificial horse are to be identified with the rivers, on the resemblance that there is flow of liquids in both, blood in the former and water in the latter. Its liver and spleen (the muscles below the heart) are hard and elevated like the mountains and hence the former are to be identified with the latter through contemplation. The hairs on the body of the sacrificial horse are to be meditated as the herbs and trees, the small and large in the former corresponding to the small and large in the latter. The forepart of the horse which has an upward ascent, is to be identified with the rising sun which also ascends up till noon.

The hind part of the horse is to be meditated as the setting sun, the resemblance being that both come anterior to their respective posterior parts, viz., the forepart and the rising sun. The yawning is lightning, because the former splits the mouth and the latter splits the clouds. Its shaking the body has resemblance to thundering, because both produce sound. Therefore, the former is to be identified through contemplation with the latter. Its making water is to be meditated upon as raining, based on the similarity that both cause moistening. Lastly, the neighing of the sacrificial horse is to be contemplated as identical with sound. Here no fancying is called for because neighing produces sound.

The whole universe is an organic whole, the parts of which are vitally connected with one another. There is really no difference between one person and another person, one object and another object, because all are made up of the same five elements, - the earth, water, fire, air and ether. Man erroneously thinks that space or ether separates one object from another. But really it does not. On the other hand, it is the connecting link among the objects, being one of the gross elements containing all the five subtle elements, the same elements which go to constitute the bodies and objects. Thus, one must know that there is no physical separation. Then what is the cause of separation which every one feels in this world? The cause is psychological, created by imagination. It is this wrong imagination by the mind that causes the feeling of separation among persons, animals, plants and other objects, which feeling of segregation and individuality causes all sorrow and misery. Therefore, one who hankers after Liberation, which is destruction of sorrow once for all, has to give up the erroneous imagination of separateness and resort to right thinking and realise the one homogeneous, organic nature of this universe. The meditations which are known by the names of vidyas or upasanas in the Upanishads, aim at this great Goal of human life. In this meditation on the horse-sacrifice, the sacrificial horse, the most important item of the sacrifice, is to be meditated as the whole universe which forms the body, as it were, of the virat-purusha, also called prajapati and hiranyagarbha in this context, who is the presiding deity of the horse-sacrifice.

The second mantra completes this imagery.

अहर्वा अश्वं पुरस्तान्महिमान्वजायत, तस्य पूर्वे समुद्रे योनिः रात्रिरेनं पश्चान्महिमान्वजायत, तस्यापरे समुद्रे योनि एतौ वा अश्वं महिमानावभितः संबभूवतुः । हयो भूत्वा देवानवहत् वाजी गन्धर्वान्, अर्वासुरान्, अश्वो मनुष्यान्; समुद्र एवास्य बन्धुः समुद्रो योनिः ॥ २ ॥

॥इति प्रथमाध्यायस्य प्रथमं ब्राह्मणम् ॥

2. The mahima (a golden vessel which is used to hold the libations at the horse-sacrifice) in front of (the sacrificial) horse, is the day. The source of it is in the eastern sea. The mahima (a silver vessel which is also used to hold the libations) behind it (the horse), is the night. Its source is in the western sea. Verily, these two glories appeared on either side of the horse (as the two sacrificial vessels). He, after having become a haya carried the gods, as a vaji carried the celestial minstrels, as an arva carried the demons, as a horse carried the men. The sea is its companion indeed, the sea is its source.

In this mantra the term mahima is used for the two vessels made of gold and silver, which are most essential for the asvamedha sacrifice, to hold the libations. These two vessels, one made of gold and the other of silver, are always placed on either side of the horse, when the sacrifice is performed. These vessels symbolise the day and the night, respectively, which follow in our world, one after the other. The golden vessel stands for the day, because both are bright in nature. The silver vessel stands for the night, most probably to symbolise the starry nights. Or, it may be because ra is common in rajata (silver) and ratri (night), or perhaps due to the reason that both silver and night are inferior to gold and the day respectively. However, it is clear that the two vessels are symbolic of the bright day and the starry night.

It is our everyday experience, that the day dawns from the eastern sea where the sun rises, and the night falls when the sun sets in the western sea. So, it is said that the source of the first mahima is in the eastern sea, and that of the second mahima is in the western sea.

The above-mentioned glories (mahima) appear in the front and at the back of the horse. The day appears in the front (of the horse), its head representing the dawn of the day, and the upper half, the ascending sun. The night falls at the back of the horse, because the lower half of it is the region of the setting sun.

haya, vaji, arva and asva mentioned in this mantra are different types of horses, and are distinguished on account of their different characteristics.

The sea is its companion and its source. The sea here may represent the Universal Self, to whom the horse is tied. bandhu is here used to indicate bandhana, that to which the horse is tied, or the stable where the horse is tied. bandhu generally means companion. The supreme Self is also the abode of the horse, to which it owes its birth, i.e., the world has come out of the supreme Self. It is said to be the yoni, the source. The world subsists in It as the manifestation of prakriti.

"The horse has its abode in the water" - says the Taittiriya Samhita, which should never be taken in its literal sense, that the horses are born of the sea, though the sea is the well-known place of their origin. The name saindhava applied to horses is so derived. As in the previous mantra the sacrificial horse has been graphically symbolised as the world, or creation in a wider sense, in order to facilitate meditation on the asvamedha sacrifice, and to divert the external actions of man to the inner life of meditation. It will be more appropriate to understand the deep import of the above passage, by interpreting it as "the world has its abode in water". Water conveys the idea of subtle elements. Water stands for all the elements, because it is really a combination of water, fire and earth, according to the tripartite creation of the gross elements (vide Chh. Up. VI-iii-3). Water is all-pervading.

Summary

In this first section, the world is compared to a sacrificial horse, and an exhaustive description of the world is presented in comparison with the different limbs of the horse. This section aims at explaining the famous and elaborate 'horse-sacrifice', with a view to giving it an esoteric and philosophic meaning. It is a fact within the range of everybody's knowledge, that the aim of the Upanishadic philosophy is to lift the individual's mind from the lower regions of samsara to the higher planes of sublime ideals. In olden days, the asvamedha was a very well-known and popular sacrifice. The sacrificer aimed at achieving victory over the kingdoms of the earth. This was the case with all those that were desirous of earthly happiness. But, people who were endowed with higher thought and experience sought to spiritualise that sacrifice, by making it a mode of conquering the lower mind, a way of inner meditation, for gaining suzerainty over one's own self. While the followers of the karma kanda stick on to the external aspect and meaning of the sacrifice, the wise seer of the Upanishad penetrates deep into its inner spiritual significance. And, thus comes to him the vision of the cosmic Spirit which the sacrificial horse symbolises.

Thus Ends the First Section Entitled Asvamedha-Brahmana in the First Chapter

SECTION II

नैवेह किंचनाग्र आसीत्, मृत्युनैवेदमावृतमासीत्-अशनायया, अशनाया हि मृत्युः तन्मनोऽकुरुत, आत्मन्वी स्यामिति । सोऽर्चन्नचरत् तस्यार्चत आपोऽजायन्त; अर्चते वै मे कमभूदिति, तदेवार्कस्यार्कत्वम्; कं ह वा अस्मै भवति य एवमेतदर्कस्यार्कत्वं वेद ॥१

1. Before creation nothing was in existence. This (world) was enveloped by death (in the form) of hunger (voracity), for hunger is death. He thought: May I have mind; then He created the mind. He, worshipping Himself, moved about. During His worship, water was produced. (Then He) thus (thought): Water was produced while I was worshipping. Therefore, this is the fire so called (because, it has the nature of brightness and pleasure). One who thus knows the (origin, etc. of) fire, for him, verily, happiness comes.

In the previous brahmana or Section, the sacrificial horse has been identified with the world and world-order, and its resting place has been declared to be the supreme Self.

This brahmana opens with the unmanifested condition of this universe before the creation of the mind and the rest. Everything was devoid of name and form. The creation was in its dormant state. The five great principles were in their unmanifested state. There was neither cause nor effect, preceding the manifestation of the universe.

This mantra may give rise to many objections that are raised by the Nihilistic school of philosophy. Was it altogether void? For, the sruti says that there was nothing before creation, which indicates the absence of both cause and effect. But, when cause and effect are totally absent, the conception of non-existence cannot arise in the mind. The absence of a pot presupposes, according to the nihilists, the non-existence of that pot. If this view is to be taken as correct, if the non-existence of the effect is to mean total non-existence, then there would arise the great danger of disharmony in the sruti texts themselves. "This was verily before, the Self alone and nothing else" (Ait. Up. I-1); "Before it was the Atman alone" (Bri. Up. I.iv.1), and other similar passages in the sruti declare that though there was neither day nor night, neither being nor non-being before the emergence of the universe, yet, however, the supreme Being was existing. It is the primary Being, for no other whatsoever preceded It. If we agree with the view that nothing was existing before the creation came into manifestation, as some of the schools of philosophy hold, then there would occur an inconsistency in the subject matter of the present topic which is immediately followed by, 'this was enveloped by death in the form of voracity'

It is not correct to say that existence presupposed a universal void or total absence of the primary cause, for we have never seen a pot coming into existence without a cause, viz., clay. No effect is produced when there is no cause. Whether or not the cause is perceptible, we can infer a cause from the effect, as we infer the clay, the cause, from the effect, the pot. It is immaterial whether the cause is perceptible or not. What is significant is the production of the effect. From this, we rightly infer that before creation the universe also must have existed in its existent cause, as pot in its cause which is existent.

The sruti says that the world was covered by death, which means that death was in existence prior to creation. Then, of course, the objection is answered by the same sruti. Now we understand the passage in this way: This creation was, before it could be distinguished by name or shape, i.e., before its manifestation, enveloped by the all-enveloping death; nothing existed whatsoever, If this passage is read and explained from the mythological point of view, death here symbolises the state of adi-pralaya, the first state of cosmic deluge. Before life manifested in creation, there was total negation of it, which is characterised by the state of death. Death is the opposite of life. Death is also known by the name of hunger. Hunger is an epithet of death. Hunger is the desire to eat. It is the tendency to the death of that which is eaten. We know by our experience that hunger, in course of time, is followed by death, for on account of hunger one eats the other. If one does not eat the other, one has to die out of hunger. Therefore, hunger refers to death. Just as when we say 'there was no pot', we refer to the absence of the pot, similarly, death refers to the absence of life, the first characteristic of creation.

But death, which corresponds to the absence of life in its manifested aspect, is not capable of thinking, unless there exists some other cause, which has properties of thinking and willing. Then death must presuppose its cause in the form of iccha-sakti, i.e., the desire aspect of the creative activity. It is this iccha-sakti that impels death to think: 'Let me have a mind'.

To put the matter concisely, prior to creation, everything that was was unmanifested. The life-vibrations were in latent form. Though the supreme Principle was there, It was in an unmanifested form. Just as earth is seen in the form of a lump of clay, and clay, as a matter of fact, manifests itself in the form of a jar, similarly, the supreme Principle manifested Itself, by virtue of Its iccha-sakti (will-power) in the form of creation. Death, in this passage, refers to the unmanifested aspect of the life-principle, which, in that condition, was temporarily devoid of iccha-sakti, the power to will.

He thought: 'Let me have a mind', and then He created the mind. Mind here corresponds to the iccha-sakti, which is a characteristic of the life-principle. This is a metaphorical illustration of the process of the projection of life. After life was projected through the venues of death, it (life) animated itself throughout. As a consequence of this animation caused by the life-principle, death disappeared, just as darkness disappears with the appearance of light, or the lump of clay disappears when the form of a pot animates the whole being of the clay. This animation of the life-principle is figuratively pointed out by the statement: 'He created the mind'.

Then what happened? Life appeared, became manifest in the form of 'willing'. This view is supported more or less by all the srutis, on similar lines.

Then it is said that He went on worshipping. Here the act worship symbolises the animation of kriya-sakti, creative power. The life principle is always understood to denote activity too, inasmuch as it is the sole cause of 'willing'. 'Worship' can denote the setting of kriya-sakti in motion, dynamism or activity. From such activity, a twofold result follows: First, there is an awareness of the activity of the mind which is described as fire. Secondly, there is a consciousness of the feeling of happiness arising from such activation of the mind which is described as water. Since both owe their birth to one source, they are commonly named arka. arc means worship. kam means happiness. The combination of these two words results in the noun arka. Worship represents fire, and its outcome, happiness, represents water, these being the third and the fourth principles in the order of creation.

While the process of creation was going on, as stated above, water was produced as an effect of worship, the animation of kriya-sakti. No sooner did He see the water, the life-principle, than was He immensely delighted, for creation had taken place. He meditated on the origin of this water-whence did it come, and how? He discovered that while worshipping or setting His kriya-sakti, the power of dynamism in motion, water, the life-principle, had sprung up. He discovered or became aware of His kriya-sakti, which was animating all, throughout, as the sole-force. It gave Him delight, as it were. Thus arka is an epithet of fire derived from the performance of worship, leading to happiness (arcate kam arkam). As already stated, fire is the third principle, and water the fourth. akasa and vayu precede them in the act of creation.

The brahmana concludes its first mantra with a phala-sruti: One who thus knows the origin, etc., of the fire element as kriya-sakti in the order of creation, for him happiness (kam) comes. The meaning is that happiness is related to the life-principle in man.

The next mantra deals with the creation of the grossest and last of the principles - earth.

आपो वा अर्क; तद्यदपां शर आसीत्तत्समहन्यत । सा पृथिव्यभवत्; तस्यामश्राम्यत्; तस्य श्रान्तस्य तप्तस्य तेजो रसो निरवर्तताग्निः ॥२ ॥

2. Water, indeed, is arka (brightness). That which was froth in the water solidified. That (mass of solidified substance) became the earth. Because of it (He) became tired. (Then) the lustre and essence of the tired and distressed (prajapati) turned into fire.

Before we proceed to describe the emergence of the earth, we shall summarise the meaning of this mantra as stated in the Taittiriya Upanishad (II-i): "From the Self, verily, space arose, from space air, from air fire, from fire water, from water the earth, from the earth herbs, from herbs food, from food semen, from semen the person."

Water is fire, because it has emerged from fire. Water is the substratum for fire, for, indeed, nothing whatsoever would exist if the life-principle had not come into manifestation. In the order of creation, too, water principle follows soon after the emergence of fire. Water is the main principle on which life subsists in this creation. From water earth was formed, i.e., out of water sprang forth the embryonic state of the universe.

The mantra states that that which was froth in the water solidified. It means that the earth sprang up. This solidification was as a result of the internal and external heat which must have been enveloping the whole atmosphere in the pre-embryonic state of the earth. It will be said later on in this Upanishad: 'In the beginning this world was just water', etc. While discussing the cosmology in the Chhandogya Upanishad, Sanatkumara, by the way, tells Sage Narada: 'It is just water that is solidified, that is this earth, that is the atmosphere, that is the sky.... all these are just water solidified' (VII-x-1). Reference to this cosmological conception is found in the Aitareya Upanishad too: 'Right from the waters He drew forth and shaped a person' (I-3).

That solid substance which was formed in water is earth. the fifth and the last principle, in the order of manifestation. In its embryonic state, it must have been as big as an egg. Egg in Sanskrit language is called anda. Most probably the epithet brahmanda for the universe, is derived from this embryonic state of the universe, when the earth was as big as an egg.

After having created the earth, which was so tedious a process, He, prajapati, became tired. It is perhaps for this reason that there is no sixth principle. From the general knowledge of physics and through observation also, we know fully well that the whole universe is animated by one common principle. Through endless ages, this common principle has remained the same throughout, without any modification in its essential nature. The statement 'He became tired' opens before us a new venue for thought and research, which stands before us and confronts us with the question, "Why He became tired and how did it prevent the further emergence of a sixth principle?". The projection of the earth was no small task for prajapati, and therefore, naturally He became tired, as everyone becomes tired after -work.

Tired and distressed as He was, His essence or lustre emerged from His body and the principle of fire was born. This fire is the first-born viraj who is identified with the sum-total of all the bodies. He possessed a body and organs, for smriti says: "He is the first embodied being". Agni in this mantra stands for viraj. sara means a mass of solid substance, the cream of slightly curdled milk. This is to illustrate that the mind assumed denser and denser form and thus all material objects of the earth were created. He became tired, because He had worked much. He became distressed because He had become separated from the supreme Self, His Abode, the stable of the sacrificial horse (vide mantra I-i-2).

brahma, the Creator began to move about manifesting as the vital energy in his creation. This vital energy is spoken of as agni. Lustre came out' means that brahma functioned as prana in all beings.

The next mantra deals with the further division of life. prajapati, as fire, divided itself in threefold ways, as the sun, air and fire. Death, which was one when creation emerged, became multiplied, vitalising all through the sun, pervading all space through air, and sustaining all life in the beings through prana.

स त्रेधात्मानं व्यकुरुत, आदित्यं तृतीयम्, वायुं तृतीयम्; स एष प्राणस्त्रेधा विहितः । तस्य प्राची दिक् शिरः असौ चासौ चेम। अथास्य प्रतीची दिक् पुच्छम्, असौ चासौ च सक्थ्यौ, दक्षिणा चोदीची च पार्श्वे, द्यौः पृष्ठम्, अन्तरिक्षमुदरम्; इयमुरः, स एषोऽप्सु प्रतिष्ठितः; यत्र क्व चैति तदेव प्रतितिष्ठत्येवं विद्वान् ॥ ३ ॥

3. He (Death) divided himself threefold, making the sun the third in respect of fire and air, and the air third with respect to fire and sun. This prana also divided itself threefold. Eastern direction is his head. Yonder one and yonder one (north-east and south-east) are his two arms. (Likewise) the western direction is his tail (hind part). Yonder one and yonder one (north-west and south-west) are the thighs. Southern and northern (directions) are sides (flanks), the sky is (his) back, the atmosphere is his belly. This (earth) is (his) chest. He (Death) is resting (standing firmly) on the waters. Wherever the knower (of this fact) goes, there (he) has a resting place (he gets a resting place).

Death became divided threefold. Those divisions were the sun (vital energy), fire (life) and air (space). It may be said here that the whole of creation, during that period had become animated with these three gross factors. Naturally, the prana also became threefold, for prana is the pervading essence in the entire creation. Whenever any factor of creation is dealt with, prana is naturally included in it. When Death was divided into three, i.e., sun, fire and air, prana also followed the same process of division. It became (1) Life in the Sun, which vitalises all things, (2) Life in the Fire, which sustains the main life principle, throughout the creation, and (3) Life in the Air (space and light).

What is that Death like? The mantra replies through a metaphor. Eastern direction is its head. North-east and south-east are its arms. Western direction is its tail or hind part. Tail means the horse-tail, horse standing as a symbol of creation as envisaged in the first Section. North-west and south-west directions are its thighs. The southern and the northern directions are its two sides, right and left. The heaven is its back like the back of a horse, projecting upwards. The atmosphere or the intermediate space is the belly of this Death. The space is used to denote the belly, for the simple reason that the endless worlds are contained only within space, even as all food that is eaten is contained within the belly. This earth which is our planet, is its chest or breast. It is resting on the waters. Quite true, for all life depends on water. sruti also says: "evam ime lokah apsu-antah-thus do these worlds are in the water." The cosmic waters are supposed to be supporting the universe from endless ages. Wherever a knower of this fact goes, there he has a resting place. In other words, one who knows that the whole of the universe is but the cosmic body of the Atman, he is revered everywhere. Wherever he goes he gets a place for resting. This is to glorify the knowledge of the emanation of the universe from the Atman in its threefold aspect of adhyatma, adhibhuta and adhidaiva.

सोऽकामयत, द्वितीयो म आत्मा जायेतेति; स मनसा वाचं मिथुनं समभवदशनाया मृत्यु; तद्यद्रेत आसीत्स संवत्सरोऽभवत् । न ह पुरा ततः

संवत्सर आस; तमेतावन्तं कालमबिभः । यावान्संवत्सरः; तमेतावतः कालस्य परस्तादसृजत । तं जातमभिव्याददात् स भाणकरोत् सैव वागभवत् ॥४ ॥

4. He, (the voracity, Death) desired: 'Let me have a second body'. (Having thus desired) He became (brought about) the union of speech with the mind. The seed that was there, (it) became samvatsara (year). Prior to him (there had been) no year. (He, the Death) reared him (samvatsara) for as long as a year. After this period (he) created him. (When he was born) He (Death) opened (his) mouth (to devour him). He (babe) made a sound (uttered) bhan. That (sound) indeed, became speech.

After having manifested himself as the first organism, in the cosmic egg, he, the Death, thought of or desired for a second body (self). His first body was viraj, containing within himself the whole organism of mundane creation. The second self which he desired for, came to his mind as vak, speech. vak is the power or medium of expression. It is quite natural that what one thinks one expresses. This correlation of 'thinking' and 'expressing' is established in this mantra.

Speech is thought expressed. No form of knowledge can find expression without the medium of speech. Speech reproduces the thought in the form of sound-vibrations. How could one express himself, if there were no speech! It evidently goes to establish the fact that soon after creating the viraj, the cosmic organism, Death thought by virtue of his mind, to create 'speech' by which he (the viraj) would be enabled to express or know his existence. It will be said later on that knowledge has for its support speech (II-iv-11). What we speak is the grossest reproduction of knowledge. When knowledge springs up in the mind, certain subtle vibrations form a group. These subtle vibrations in a group express the subject of knowledge. And, when this expression takes place through the medium of sound, we call it speech. So speech presupposes a thought, a knowledge, for what is not knowledge can never find its expression in any form, whatsoever. "Verily if there were no speech, neither right nor wrong, neither good nor bad, neither pleasant nor unpleasant would be known. Speech, indeed, makes all this known." (Chh. Up. VII-ii-1). Speech, thus, is the first conception of knowledge, and the first expression of thought. Before speech, thoughts must have been infinite in nature. It was only speech which gave them a definite shape, the form of knowledge.

Thus, he (the Death) brought about the union of speech with the mind. He created speech which reproduced his mind in the form of knowledge. What is that knowledge? It is the three vedas, the source of all secular knowledge, the first expression of hiranyagarbha, the first sound in creation, the first kind of knowledge.

The cosmic mind, after having caused union with speech, after having reflected upon the vedas (knowledge), conceived division in eternity. Before this, there was no division of time. This division so happened, because he reflected upon the past through his mind and effected its (mind's) union with speech. The reflection on past gave birth to the conception of the time factor, just as the reflection on ether gives the conception of space. Time factor naturally involves in it three divisions, - past, present and future.

The seed of creation was there in that embryo, the viraj. It had not manifested as yet. It was in a latent state, awaiting the completion of duration, when the egg would get broken and the first embodied soul would spring up. He was waiting so long as a period which was equivalent to our one year. It is this intermediate duration of time which is well known as a year among us.

Now, it was time for the viraj to come out of the egg. Creation took place and viraj was born, who was the first in the embodied mundane creation.

The babe is born. This new-born babe is universe in miniature. It sprang out of Death. For, every kind of life presupposes Death as its cause. Death causes life to manifest. The whole of creation owes its origin to Death.

Death now wanted to swallow the new born babe - says the Upanishad. But then, the question arises, why did It want to eat its own offspring? The reply is just simple, of course, philosophical. Life is born for Death. No sooner does one come into manifestation, he faces death which always stands before him. Life which has followed death is nothing in the vast span of eternity. Behold the life in the universe, from the view-point of the seer of this Upanishad. Is it not in the ever-devouring and voracious jaws of Death? The endless universes which are born of time and limited by space and causation, are fleeing every second towards Death. There is nothing whatsoever in this universe which does not meet with death, for the universe is ever subjected to Time (kaala) which never survives the next second, but passes away instantaneously. Time is the ruling factor of all beings. The universe is divided into infinitesimal fractions of time. The so-called span of universe-life is nothing before Infinity, as it also is bound to be devoured by Death. The wise seer of this Upanishad has foreseen the ultimate end of life, and describing it graphically, he says that the new-born babe faced Death who was intent on devouring it as soon as it was born. Continuing the graphic description, the Upanishad says that the babe cried in terror as everyone of us would do when death approaches. This also suggests that the worlds were born with a terrorised complex, with an innate and natural fear for death. It is not a poetic fancy, but a glaring truth, for everyone is afraid of death.

Terribly frightened by the presence of Death whom he had never seen before, but whose fear was in him due to the fact of primal ignorance, the babe, it is said, produced the sound bhan. It was the first manifestation of speech as sound. It is called vak, for vak is that which is spoken. 'Whatever sound is there, it is just speech' (I-v-3).

स ऐक्षत, यदि वा इममभिमंस्ये, कनीयोऽन्नं करिष्य इति; स तया वाचा तेनात्मनेदं सर्वमसृजत यदिदं किंच-ऋचों यजूंषि सामानि छन्दांसि यज्ञान्

प्रजाः पशून् । स यद्यदेवासृजत तत्तदत्तुमधियत; सर्वं वा अत्तीति तददितेरदितित्वम्; सर्वस्यैतस्यात्ता भवति, सर्वमस्यान्नं भवति, य एवमेतददितेरदितित्वं वेद ॥५ ॥

5. He thought thus: 'Verily, if I kill him (the new-born babe), I shall make little food. Thus (on this reflection) he (Death) by that speech and by that mind created all this, whatever there is (existing) here: the rigveda, the yajurveda, the samaveda, the metres, sacrifices, men and animals. Whatever he (thus) created, all that he resolved to eat. (Because Death) verily, eats all, therefore aditi is so called. He who thus knows how aditi came to have this name (he who knows him in his nature as aditi), he becomes the eater of all this, everything becomes his food.

We have seen how He manifested himself as time and space. In this mantra, the creation of the gross universe is described.

After having resolved to kill the little babe, He, the Death, thought that it would be unwise to kill him now for He would be making very little food. Creation had just sprung up. There were neither animals nor men, nothing whatsoever, except life, which had just manifested in the form of viraj. That too, Death wanted to devour. But it would be too little for him, for how can the all-devastating Death be satisfied with a meagre quantity of food! Moreover, viraj represents food and the producer of food. If the producer of food itself is eaten up, then there will be no more production of food to eat. So, Death abstained or desisted himself from killing the first-born. And at the same time, with the help of speech and mind and through their union, created all that exists here.

With the united operation of speech (knowledge) and mind (will-power), i.e., jnana and iccha combined, He manifested himself as the three vedas-rigveda, yajurveda, samaveda; the seven metres-gayatri, ushnik, anushtubh, brhati, pankti, trshtubh and jagati - in which the stotras, sastras and other scriptures are composed and sung; the sacrifices, men and animals.

In the foregoing mantra, it has been already said that Death projected viraj through the union of speech with the mind. That union of the mind with speech was then in an unmanifested state, while here the reference is to the manifestation of the already existing vedas. In the beginning the knowledge too was not in a manifested form. It was remaining unexpressed for want of a medium. It was only an idea in the mind. The mind was able to conceive knowledge, though it could not give expression to it in any form. When the knowledge (jnana-sakti) came to be expressed through the medium or channel of speech in the gross universe, life found ample scope for spontaneous evolution and expression.

Now, the knowledge expressed itself in the form of vedas, metres and sacrifices. And these, in the scheme of creation, were further expressed, in course of time, in a still grosser form, by men who possessed the knowledge so expressed and utilised it.

This development in the said universal scheme must have taken a pretty long period. And perhaps, it was much later, when man sang the vedas in different metres and started sacrificing animals for his own sake. So, it should not be argued that He created vedas, etc., to be sung, sacrifices to be performed, animals to be sacrificed and men to sacrifice those animals. We shall be losing sight of what this mantra wants to present to us, if we unjustly infer that everything was created only for the sake of man. What exactly the Upanishad aims to teach us is that everything, whether animate or inanimate, sentient or insentient, movable or immovable, big or small, was created by Him alone. Creation should not be ascribed to any other being. It is He the Creator in whom all this exists and gets dissolved at the end. The fact of creation is a sort of His self-expression, which finds an interesting explanation and description in the mystic-minded sages, This process of His self-expression is like a long chain, which, though it contains in it diverse pieces or links, is one in essence.

The mantra states that whatever He projected, He was intent on eating. It may be explained in this way: Every object which is manifested and has name and form, is bound to be victimised by Death. It is sure to perish, for it is limited by time, space and causation. It might survive the blows of time for a good number of years, but in the end it has to die, for nothing that is born can be eternal. Creation as a whole is short-lived, and everything in it is pre-resolved to be eaten away by Death. Therefore, it is but natural that Death must have intended to subject viraj to His inevitable law.

Who is this Death? Once again the sruti follows the same course of describing Death, and identifies Him with aditi whom the rigveda declares to be everything in this universe: "aditi is heaven, aditi is the sky, aditi is the mother and He is the father..... etc."

How did Death come to have this name aditi? It is because Death is all-consuming, all-enveloping and animating the whole being of creation. As stated in the just preceding paragraph, aditi is heaven, sky, mother, father, etc. He is immanent in the whole being of creation. Because of this common function of animation and immanence, the Death is identified with the aditi of the rigveda. Death possesses this characteristic and therefore he came to have this name aditi which the text refers to.

One who knows that Death is aditi, because It consumes all, becomes the eater of all. He becomes identified with everything. One who knows that there is one all-pervading factor in the entire cosmos, becomes freed from the clutches of birth and death. The text metaphorically puts this fact by saying that He becomes the eater of all this, all names and forms.

To such a man who feels himself identified with everything, everything becomes his food. He develops that cosmic vision, by which his Self becomes immanent in every speck of this vast creation. Then, all that others enjoy becomes his enjoyment, all that others eat becomes his food. So the mantra says: everything becomes His food.

सोऽकामयत, भूयसा यज्ञेन भूयो यजेयेति । सोऽश्राम्यत्, स तपोऽतप्यत; तस्य श्रान्तस्य तप्तस्य यशो वीर्यमुदक्रामत् । प्राणा वै यशो वीर्यम्; तत्प्राणेषूत्क्रान्तेषु शरीरं श्वयितुमधियत; तस्य शरीर एव मन आसीत् ॥६ ॥

6. He thus desired: 'Let me again perform sacrifice with the great sacrifice'. He became tired. He was afflicted by distress. (Then) the glory and vigour of the tired and distressed (Death) departed. The vital breaths are verily glory and vigour (of the body). (So) after the departure of the pranas (out of the body), the body began to swell. (But) his mind, indeed, was (set) on the body.

The previous mantra has explained the projection of this universe starting from vedas and ending with animals, i.e., from knowledge to ignorance. This and the succeeding mantras go to interpret the sacrificial horse and the asvamedha sacrifice concealed in etymological camouflage.

The scheme of creation has thus been perfectly set in motion. Death, who has been attempting hard to put everything in order, has become immanent in the entire creation. The term 'death' remains merely as an epithet for Him, for He is much more than Death. He is life expressed. He is now the creator, prajapati concealed, as it were, in the womb known as hiranyagarbha. He has become the cause of all subsequent creation. The process of creation is in a far advanced state. Knowledge has become manifest and has given a definite shape to the course of action. In this scheme of creation, man is born with the special privilege of thinking and contemplating on higher matters which are far beyond the reach of other beings. In him springs up the desire to know the Reality behind the gross universe and an aspiration to soar high in the sublimities of philosophical knowledge. Of course, knowledge is inherent in him, as it has followed him throughout, right from the dawn of creation. This mantra and the next present this quest of man in terms of sacrificial horse and horse-sacrifice respectively.

Sacrificial horse, as a rule, is sanctified and assigned to the gods, the divinities. The performer of this sacrifice purifies the horse by means of specific rituals and then lets it free for a year. In the same way, the individual soul has to resolve to make a greater sacrifice. He has to purify his entire being-senses, mind and his gross nature. Purification of one's own nature constitutes the first item in this sacrifice. For, without having it purified, it is unfit to be dedicated for higher purposes. Undoubtedly, the task is not a small one, because it entails great effort and continuous struggle. The individual is liable to become tired and distressed in this process. His organs may not be strong enough to co-operate with him in this great attempt. But in course of time, the entire bundle of impurities, which has shaped his nature, may depart. It is only after this sanctification that he will become fit for higher meditation which this mantra refers to in sacrificial terms.

Sacrificial horse denotes the individual soul who has to cast away the impurities of his being and get himself prepared for the highest sacrifice. He has to reject names and forms and realise his identity with the Supreme Being who transcends all, who is the prompter of Death, whom the Death does not know, whose body is Death, who rules Death from within- the Atman-Brahman.

Going deep into the mantra we find that it deals with the following points: (1) He desired to perform a greater sacrifice; (2) He performed the sacrifice and became tired; (3) His reputation and strength departed on account of the hard sacrifice that he performed; (4) after the departure of organs, his body swelled; and (5) His mind did not leave the body. The individual soul attempts at sacrificing his entire animal nature, and plunges into the task of purifying himself and becomes tired. To shed off the animal nature is not an easy affair and one has to lose one's individuality and secular relations. The individual Jiva finds, as it is natural, that his entire being is undergoing an overhauling process, and this is the intermediate state in the individual's progress to the Supreme. However, he is very careful, for he has been intently watching the overhauling that is taking place in his being.

Next follows the projection of purity and success in attempting at the horse-sacrifice.

सोऽकामयत, मेध्यं म इदं स्यात्, आत्मन्व्यनेन स्यामिति । ततोऽश्वः समभवत्, यदश्वत्; तन्मेध्यमभूदिति, तदेवाश्वमेधस्याश्वमेधत्वम् । एष ह वा अश्वमेधं वेद य एनमेवं वेद । तमनवरुध्यैवामन्यत । तं संवत्सरस्य परस्तादात्मान आलभत । पशून्देवताभ्यः प्रत्यौहत् । तस्मात्सर्वदेवत्यं प्रोक्षितं प्राजापत्यमालभन्ते । एष ह वा अश्वमेधो य एष तपति, तस्य संवत्सर आत्मा; अयमग्निरर्क, तस्येमे लोका आत्मान, तावेतावर्काश्वमेधौ । सो पुनरेकैव देवता भवति मृत्युरेव; अप पुनर्मृत्युं जयति, नैनं मृत्युराप्नोति, मृत्युरस्यात्मा भवति, एतासां देवतानामेको भवति ॥७ ॥

॥इति प्रथमाध्यायस्य द्वितीयं ब्राह्मणम् ॥

7. He desired thus: May this (the swollen body) of mine become fit for sacrifice. May I become embodied through it. Because (it) swelled, therefore it became (known as) a horse; that became fit for sacrifice. Thus, that indeed, is the origin of asvamedha sacrifice. He (who) knows him thus, verily, knows the asvamedha. Letting it (the horse) remain free, he reflected upon it. After a year, he sacrificed it (the horse) for himself and (also) assigned the other animals to the gods. Therefore, they (all those who perform sacrifices) sacrifice to prajapati the sanctified (horse) which is dedicated to all the gods. That which gives forth heat (sun), that, indeed, is asvamedha. The year is his (sun's) body. This earthly fire is arka (the universal fire). These worlds are his self (body). These two (fire and the sun) are arka and asvamedha. Again, both of them are indeed, the same god, Death. (He who knows this) conquers further death. Death obtains him not. Death becomes his self (body). He becomes one (becomes identified) with these gods.

He, the hiranyagarbha desired to purify his being, as to make it fit for the great sacrifice which has been explained in the commentary of the preceding mantra. He thought of embodying through his purified being.

Because the body had undergone swelling, so it is known as asva which means 'a horse'. In spiritual terminology, it must refer to the nature of the individual, which is the vehicle of individual activity. And because it became fit for a sacrifice, therefore the horse-sacrifice came to be known as asvamedha. asvamedha sacrifice is a process of purifying one's self from the instinctive animal nature and making it fit to be consecrated to gods, i.e., fit for higher attainments, and thereby asserting an unquestioned and undisputed triumph over one's own lower self.

The text says: "He who knows it thus, indeed knows the horse-sacrifice." It further says: "Let one imagine himself as the horse and remain free for a year and then sacrifice it to himself and despatch the other animals to gods." In short, the mantra expresses through these lines, that one should perform the horse-sacrifice to himself, rather than for others whom he wants to conquer.

Horse-sacrifice is the sun that shines and gives light to all. The year is his body, that is to say, his body corresponds to the time factor. What is that for which it is called arka and used by the sacrificer? This fire is all-pervading arka, because its limbs are these three worlds. So fire and sun are arka and asvamedha. Again these two are identical with Death. Fire denotes the sacrifice and sun stands for the result of sacrifice. These two are the same god, Death. This Death is the same deity, of whom there is reference in the very beginning of this section, who was enveloping everything that existed and who subsequently became fire, etc., and divided himself in three ways.

One who knows through meditation, what has been said just now about Death, wards off death and thereby rebirth also. He is not born again, and therefore, death has no chance to operate over him. He himself becomes identical with Death, hiranyagarbha, and thereby, becomes one with these deities for whom the sacrifices are performed. He becomes the Self of all.

Summary

This section mainly deals with the topic of creation and presents a systematic scheme of world-evolution. Starting right from the unmanifested state of creation referred to by the term Death, the section, step by step, proceeds with the emergence of five great principles in the system of creation, the formation of an embryo in the water, the formation of earth, and the birth of the first-born viraj. The interesting conception of the birth of time factor and the production of sound, leads to form a definite idea about the genius of the seers of the Upanishad who so thought of it long, long ago, and whose primal knowledge all of us inherit today. Death has been philosophically brought about throughout the section and it is a true presentation of it.

The last two mantras are very deep in their import and mystic in expression. They give a beautiful representation of the famous horse-sacrifice, which is the main topic of the first section. The horse-sacrifice can be viewed from a different perspective which will be very interesting to those who wish to understand the rituals of the sacrifice in the spiritual and philosophic perspective. The importance of cosmic identification is stressed in almost every mantra at the end.

The Seer of the Upanishad seems to have tried his utmost to express a big volume of philosophical truth in an aphoristic style. Therefore, it needs a speculative and penetrating understanding to grasp the real import.

Thus Ends the Second Section Entitled

Agni-Brahmana in the First Chapter

SECTION III

द्वया ह प्राजापत्याः, देवश्चासुराश्च । ततः कानीयसा एव देवाः ज्यायसा असुरा त एषु लोकेष्वस्पर्धन्त; ते ह देवा ऊचुः हन्तासुरान्यज्ञ उद्गीथेनात्ययामेति ॥१ ॥

1. The offsprings of prajapati were indeed twofold, the gods and the demons. Therefore (naturally), the gods (were) fewer in number, (and) the demons (were) numerous. They (gods and demons) rivalled with each other. (Therefore) indeed, they, the gods said: let us now surpass (these) demons in the sacrifice through udgitha.

In this mantra the philosophy of good and evil is explained allegorically. The descendants of prajapati were of two classes, gods and demons. Gods were virtuous and the demons were directed merely by secular goals. Naturally, gods were few in number and demons were numerous. Both of them rivalled with each other for the ownership of these worlds. This sort of rivalry continued for a long time, till at last gods decided amongst themselves to defeat the demons through the aid of udgitha,1 in the sacrifice.

Since the beginning of creation, there have been the good and the virtuous, as well as the bad and the vicious. Gods represent the virtuous in whom the quality of sattva is predominant and who have purified thoughts and refined actions, actions that are recommended by the laws of conduct. Demons represent that particular class or nature of people, which is influenced and goaded by the twin forces of rajas and tamas and which delights and takes pleasure in purely selfish affairs. This class or nature is very much opposed to the other one.

The gods and the demons are not different from man.

1 The udgitha is a song which occurs in the second chapter of the samaveda. The hymn begins with the mystic syllable Om. The chanter-priest is called udgata.

These twin forces exist within him and come to express themselves through the medium of speech and other organs of action and knowledge. When they are immaculate under the influence of pure thoughts and right actions, they become gods, the shining ones. When they are impelled by vicious thoughts, directed merely for one's own petty ends and sense indulgence and opposed to the gods, they are called demons. Gods perform only those actions that are enjoined in the scriptures and which do not oppose the general conduct. The demons base their actions on perception and inference and are goaded by something or other which is not of permanent moral value. In this mantra, the terms 'god' and 'demon' stand for the sum-total of sense-organs, which by virtue of good actions is named 'god', and by the force of vicious actions is known as 'demon'.

The gods were outnumbered by the demons who were numerous. It is because the senses are strongly inclined to enjoying the gross objects and give very little attention to those deeds that are recommended by the scriptures.

Goodness is very difficult and rare to achieve, whereas vice and irreligiousness are always rampant. It is because the senses have a tendency to go out into the gross, visible world of objects, and not to see what is internal and spiritual. This is the reason why the demons who represent the ordinary class and nature of creation, surpass the gods in number.

sattva is a spiritual and divine quality. When it preponderates, righteousness and virtue prevail in creation, and truth, purity, non-violence and other divine qualities are practised by people. There is then absence of wrath, anger, lust, jealousy and other demoniac qualities. People become good and sweet-natured, tranquil and simple. They do not act merely to achieve secular ends and for their own individual profit. Vulgarity and sensuality become extinct. Preponderance of sattva equally affects plants and animals too. When sattva prevails upon man, it is expressed through the medium of his senses and mind. One who is sattvic believes in things spiritual and not in enjoyments that are visible and sense-engendered. He knows that the things based on sense-perception and inference are not lasting and that they delude the senses, while matters spiritual have a permanent value. sattva expresses itself through good thoughts, good speech, good hearing, good seeing, good smelling, good touching and good deeds, while rajas and tamas have their field of operation in the gross and sensuous activities, viz., lust and the like. rajasic and tamasic people are attached to things mundane. They indulge in sensuality, vulgarity, wrath, passion and evil thoughts. While sattvic people (devas) have bright, white complexion, rajasic and tamasic people (demons) have dark red and dark black complexion, respectively. sattva stands for purity, rajas for hectic activity and tamas for total ignorance. Naturally, gods are fewer when compared to the demons who are numerous. Demons have a good following, because the majority of people are impelled by the force of ignorance, to perform vicious actions for self-indulgence. The rise of rajas and tamas (demons) is solely due to the mentality of man, which has grown grosser and grosser, in the midst of the external objects of sense-enjoyment. Gods have limited followers, because they condemn sense-enjoyment which is very pleasing to all, and practise only those thoughts and actions that are right and just.

A regular warfare is going on in the world between these two forces, gods and demons, good and evil. Whenever an individual is inclined to cultivate good thoughts and good actions according to the rules of righteousness enjoined in the scriptural texts, there emerges the god in him, and manifests himself through his entire organs. Similarly, when an individual is led by sense-perception and sense-enjoyment and is inclined to indulge in vices that are bitterly opposed to the rules of righteousness, there manifests the demon in him. When the former is prevailing over the individual, the latter is subjugated. Similarly, when the latter gets the upper hand, the former lies dormant. Since the dawn of creation, these two forces of nature have been vying with each other. Sometimes sattva prevails and people become pure and pious. At other times, rajas and tamas prevail, and there is preponderance of demerit resulting in degradation. Gods have been, for long ages, standing in combat with the demons. In Indian mythology, it has been named as deva-asura-sangrama, battle between gods and demons. Sometimes the gods were defeated and they hid themselves in jungles and caves, till some higher force like vishnu came to restore to them the kingdom of heaven. This warfare is continuing even to this day. Sometimes, divinity reigns supreme in the individual and the society, and at other times demoniacal nature catches hold of the heaven of gods and rules, till it is ousted by the higher divinity.

In the course of this rivalry, as the text puts it, once the gods thought and decided that they would perform a sacrifice and sing udgitha and thereby defeat the demons. They thought of meditating and repeating holy mantras through the vital force. Sacrifice and udgitha chanting here stand for holy actions through the senses. By the performance of righteous acts, one can ward off evil influence. Sacrifice really means, as has been already said in the previous section, the destruction of lower nature. Sacrifice denotes a process of sanctification of one's own nature. udgitha here means meditation. The impure and vicious force (demons) can be defeated only by means of sacrifice and meditation and chanting of udgitha. Therefore, the gods thought to purify themselves in entirety and become holy, so that the evil forces would become extinct. They took up the organ of speech for this purpose.

ते ह वाचमूचुः त्वं न उद्गायेति; तथेति, तेभ्यो वागुदगायत् । यो वाचि भोगस्तं देवेभ्य आगायत्, यत्कल्याणं वदति तदात्मने । ते विदुरनेन वै न उद्गात्रात्येष्यन्तीति, तमभिद्रुत्य पाप्मनाविध्यन्; स यः स पाप्मा, यदेवेदमप्रतिरूपं वदति स एव स पाप्मा ॥२ ॥

2. They (gods) said to the (organ of) speech: 'sing udgitha for us'. 'So be it' (said) speech (and) sang udgitha for them. Whatever pleasure (is) in speech, (it) secured for the gods by singing, (and) whatever good speech is there, that for itself. They (demons) knew (that the gods) would surpass them through their singing of udgitha. (Thinking thus they) rushed at it (the speech), pierced (it) with sin. This indeed is that sin which speaks (what is) wrong. This indeed is that sin.

The gods asked the organ of speech, to sing udgitha. They asked speech to become the agent of warding off the evil by becoming holy: Speech obeyed their instructions. It made itself pleasant to the gods and spoke what was good. Therefore it became 'good speech'. Evil and dark forces in an individual do not allow the sattva to express and predominate. Here also they counteracted the efforts of speech and charged the speech very badly till it uttered evil words. This evil is that what we find today, when one speaks what should not be spoken and what is forbidden to be spoken. Through the promptings of this devilish force, one speaks unpleasant words, utters dreadful expressions, makes false and vulgar statements, because one's speech has been contaminated by the vicious and undivine traits of the individual.

Here, the organs of the body are identified with the gods when they manifest the divine nature in them, and with the demons when they express the undivine traits.

अथ ह प्राणमूचुः त्वं न उद्गायेति; तथेति, तेभ्यः प्राण उदगायत् । यः प्राणे भोगस्तं देवेभ्य आगायत्, यत्कल्याणं जिघ्रति तदात्मने। ते विदुरनेन वै न उद्गात्रात्येष्यन्तीति, तमभिद्रुत्य पाप्मनाविध्यन् स यः स पाप्मा, यदेवेदमप्रतिरूपं जिघ्रति स एव स पाप्मा ॥३ ॥

3. Then (the gods) said to the nose: 'sing the udgitha for us'. 'So be it' (said) the nose (and) sang the udgitha for them. Whatever pleasure (is) in the nose, (it) secured for the gods by singing (and) whatever good smell is there, that for itself. They (the demons) knew (that the gods) would surpass them through that singer of udgitha. (Thinking thus they) rushed at it (the nose), pierced (it) with sin. This indeed is that sin which smells (what is) wrong. This indeed is that sin.

When the speech was struck down with evil, then the nose was asked to appear and sing hymns to purify itself. The nose also caught the infection of evil and began to smell bad odour. It is for this reason that even today the nose smells bad things.

अथ ह चक्षुरूचु; त्वं न उद्गायेति; तथेति, तेभ्यश्चक्षुरुदगायत् । यश्चक्षुषि भोगस्तं देवेभ्य आगायत्, यत्कल्याणं पश्यति तदात्मने । ते विदुरनेन वै न उद्गात्रात्येष्यन्तीति, तमभिद्रुत्य पाप्मनाविध्यन् स यः स पाप्मा, यदेवेदमप्रतिरूपं पश्यति स एव स पाप्मा ॥४ ॥

4. Then (the gods) said to the eye: 'sing the udgitha for us'. 'So be it' (said) the eye (and) sang the udgitha for them. Whatever pleasure (is) in the eye, (it) secured for the gods by singing (and) whatever good sight is there, that for itself. They (the demons) knew (that the gods) would defeat them through that singer of udgitha. (Thinking thus they) rushed at it (the eye), pierced it with sin. This indeed is that sin, which sees (what is) wrong. This indeed is that sin.

Now the eye was brought forward to do the task of sacrifice and chanting. It secured the common good for the gods and retained fine seeing for itself. It, too, was struck down by vicious infection and it began looking at unholy scenes, evil objects and dirty matter. It is this evil which is persisting in the eye even today, when one sees something which is unholy or obscene.

अथ ह श्रोत्रमूचुः त्वं न उद्गायेति; तथेति, तेभ्यः श्रोत्रमुदगायत् । यः श्रोत्रे भोगस्तं देवेभ्य आगायत्, यत्कल्याणं शृणोति तदात्मने। ते विदुरनेन वै न उद्गात्रात्येष्यन्तीति, तमभिद्रुत्य पाप्मनाविध्यन् स यः स पाप्मा, यदेवेदमप्रतिरूपं शृणोति स एव स पाप्मा ॥५ ॥

5. Then (the gods) said to the ear: 'sing the udgitha for us'. 'So be it' (said) the ear (and) sang the udgitha for them. Whatever pleasure (is) in the ear, (it) secured for the gods by singing (and) whatever good hearing is there, that for itself.

They (the demons) knew (that the gods) would surpass them through that singer of udgitha. Thinking thus they rushed at it (the ear), pierced (it) with sin. This indeed is that sin, which hears (what is) wrong. This indeed is that sin.

Then the gods asked the ear to come forward and do the needful to surpass the evil. But it was also pierced with the evil of hearing what should not be heard and what was improper. Therefore, even to this day, ear hears all unholy sounds.

अथ ह मन ऊचुः, त्वं न उद्गायेति; तथेति, तेभ्यो मन उदगायत्; यो मनसि भोगस्तं देवेभ्य आगायत्, यत्कल्याणं संकल्पयति तदात्मने । ते विदुरनेन वै न उद्गात्रात्येष्यन्तीति, तमभिद्रुत्य पाप्मनाविध्यन्; स यः स पाप्मा यदेवेदमप्रतिरूपं संकल्पयति स एव स पाप्मा; एवमु खल्वेता देवताः पाप्मभिरुपासृजन, एवमेनाः पाप्मनाविध्यन् ॥६ ॥

6. Then (the gods) said to the mind: 'sing the udgitha for us'. 'So be it' (said) the mind (and) sang the udgitha for them. Whatever pleasure (is) there in the mind (it) secured for the gods by singing (and) whatever good thinking is there, that for itself. They (the demons) knew (that the gods) would surpass them through that singer of udgitha. (Thinking thus, they) rushed at it (the mind), pierced (it) with sin. This indeed is that sin, which thinks (what is) wrong. This indeed is that sin. Thus, (the demons) also tainted the other deities (of skin, ́etc.) with sin, and thus pierced them with sin.

After the ear was also infected by the rajasic and tamasic tendencies, mind was asked to perform the sacrifice and sing the hymns of udgitha. That too underwent the same fate. It was contaminated by evil and it imbibed evil thinking. It is this evil that has caused the mind to think improper, unholy and wrong thoughts.

Likewise, the deities of the remaining sense-organs and the motor-organs were tried one by one. But they, too, got evil. None of them could do the task of sanctification well and transcend evil.

अथ हेममासन्यं प्राणमूचुः त्वं न उद्गायेति; तथेति तेभ्य एष प्राण उदगायत्; ते विदुरनेन वै न उद्गात्रात्येष्यन्तीति, तमभिद्रुत्य पाप्मनाविध्यन् स यथाश्मानमृत्वा लोष्टो विध्वंसेत, एवं हैव विध्वंसमाना विष्वञ्चो विनेशु, ततो देवा अभवन्, पराऽसुराः भवत्यात्मना, परास्य द्विषन्भ्रातृव्यो भवति य एवं वेद ॥७ ॥

7. Then (the gods) said to this vital force dwelling in the mouth: 'you sing udgitha for us'. 'So be it' (having said thus) the vital force sang the udgitha for them. They (demons) knew (that the gods) would surpass them through this singer of udgitha. (Having thought thus the demons) rushed at him (the vital force) (and) desired to pierce him with sin. Just as a clod of earth striking against a rock is destroyed, so destroyed and blown in all directions they (the demons) perished. Then the gods became (their own selves), the demons were defeated. He who knows thus, becomes his true Self and his envious kinsman is defeated.