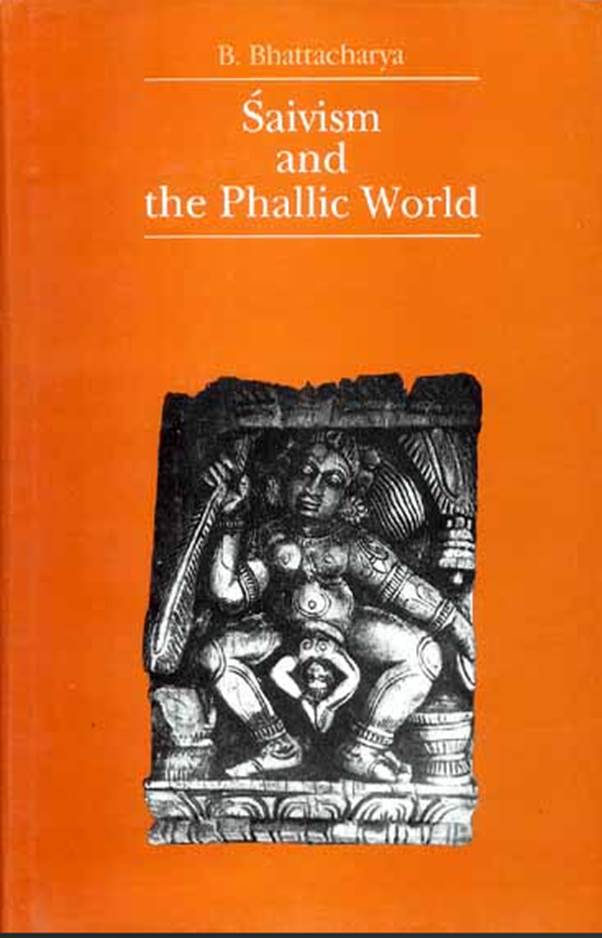

Saivism

And

The Phallic World

B. Bhattacharya

Volume I

Munshiram Manoharlal

Publishers Pvt Ltd

यद् यद् कर्म करोमि तत् तद् अखिलम्सम्भो त्वदराधनम्

YAD YAD KARMA KAROMI TAT TAD AKHILAM

SAMBHO TVADARADHANAM

All my actions, oh Sambhu, are but offerings to Thee.

Contents

Review by Dr. Suniti kumar Chatterji

Transliteration of Sanskrit World

III. Religious Love and Hindu Catholicism.

IV. East-West: An Arrogant Volte-face.

V. The Tamils and Siva Evolution. References

2. THE PHALLIC TRADITION, GODS AND THE ANCIENTS

III. The Phallic World with the Antecedents.

IV. Sex and Religious Feruour.

V. The Birth of Gods. References.

V. Beginning of Abstract Thinking.

VII. The Mother for the Latins.

IX. Forms of the Mother. References.

4. RELIGION AND THE HINDU SYSTEMS

II. The Antecedents of Sämkhya.

IV. Vedänta: God and Theological Need

VI. Hindu Polytheism and Siva. References.

I. Historical Forces on the Move.

IV. Old Forms in New Religions. References.

Saivism and the Phallic World is a formidable treatise by any standard. Many have favoured the tome as the only standard work on the treatment of Saivik thoughts. Readers and students have welcomed the book particularly be- cause of the broad canvas on which it has been laid, opening up vistas of comparative religious trends in history of mankind, specially drawing attention to the Siva and Tantra trends, in all types of human society, ancient and modern.

But for the public appreciation it has received a heavy and ponderous book like Saivism and the Phallic World would not have entered into a second edition. In fact the publishers have done the reading public a service by venturing into this project, after the book had disappeared from popular book-shops for over three years.

From the date it had been first published (1975) to date certain aspects dealt within the text called for some special brush ups. These have been included as Additional Notes. A typeset book of this size, inevitably, erred over certain print and other slips. The author as well as the publishers have taken great care in eliminating these errors, and redressing certain phraseologies for the sake of clarity and form. To this extent the present edition has become far more reliable.

The Index of the first edition had never been to an expected standard. This major deficiency has now been removed by adding a completely remodelled Index, on which the author himself has worked very hard. Dr. V.N.Chibbar deserves thanks for going through this part of the work very thoroughly, and arranging the index with scientific and intellectual precision.

One of the most valuable addition to this edition is the sponataneous review from the eminent savant and orientalist-linguist the Late Dr. Suniti Kumar Chatterji, National Professor of Humanities, on this book. This review has been called 'spontaneous' becaue at the time of writing this review Dr. Chatterji and the author, who used to live in the West Indies (Trinidad), had not known each other. The later bonds were established between the two only through the medium of this book.

The author expresses his thanks to the publishers for undertaking this venture. As one of the leading publishers in India of Oriental treatises the house of Messrs. Munshiram Manoharlal is reputed internationally. Thanks are also due to my daughter Mrs. Atreyee Cordiero and my student-friend Shri Sunil Jha both of whom have been good enough to bear with the tantrums and idiosynorasies of an octogenarian perfectionist.

New Delhi BRAJAMADHAVA BHATTACHARYA

16 February 1993

Review by Dr. Suniti Kumar Chatterji

Saivism and the Phallic World, by Professor Brajamadhav Bhattacharya, published by the Oxford and I.B.H. Publishing Company, New Delhi, 1975, in two volumes, p. 1048.

This is a stupendous book, and in its compact 1048 and more pages written in forceful and most readable English is crammed a mass of information of quite an encyclopaedic extent on almost all matters dealing with religion, both popular and higher, philosophy, mysticism, history, ethonology and everything that has got a reference or a relevance to the human phenome- non. The author is remarkably qualified to handle such a vast amount of scientific and philosophical erudition. He is born in a Brahman family with all the heritage of traditional Brahmanical scholarship and ideology. He is a present-day Indian scholar of literature and has been teaching the subject for over quarter of a century. He has moreover been an ardent seeker after the Reality behind life, and in this matter he has not confined himself to formal philosophical and scientific enquiry but also has taken note, with the spirit of an humble enquirer along the lines suggested by mystic adepts, of the ritual and dogmatics, symbolistics and myth, folklore and traditions, and whatever has developed and has found a place in human culture in its manifold essay for arriving at the unseen and the unknown.

From its title, this book would appear to give a detailed exposition of one aspect of Hinduism, namely the worship of the Divinity through the concept of Siva, the Deity of destruction and regeneration, who represents not only the forces of creation, destruction and recreation but also typifies the action of the live forces in all existence. A look into the wonderfully diverse range of topics treated in this great book would seem to suggest that no aspect of life and creation which comes within the purview of religion and thought has been left untouched by the author, who seems to embrace everything in the wonderful sweep of his view. In the Mystic Mother Section of the first volume of his book, the author has brought the topic of fundamental importance in life and being which centers round Sex-the Lingam and the Yoni-the Creative forces through the polarities of the Father and the Mother which merge into each other, the Ardha-Nariswara or the Androgyne. All this inevitably leads through Bhakti or the Abandan of Faith and Love to the Divine Essence in its Nirguna and Saguna forms. The subject has been presented with uncommon knowledge and conviction, and this makes the book a source of serious and reflective reading of both high and profound unction.

In the second volume we have an exposition of the various aspects of Saivaism which according to the author's experience, forms the quintessence of Religion. In this volume, Professor Bhattacharya also gives an exposé of the significance of a number of Saiva myths and legends which are sometimes very little known to the domain or esoteric students of myths- of God and Goddesses and their doings, and they always bring to us startling suggestions and conclusions and give us food for fresh thought. In this and all other respects, the Saivism and the Phallic World is a unique scientific work, unrivalled in its field.

Sex is treated as a basic fact of life-as the Hindu idea is, it is one of the 4 Great Ends of Man's Existence (Chaturvarga, Purushartha), which are (1) Dharma a virtue in conforming in life to the Eternal Law of Being which holds in itself everything, (2) Artha or Wealth (which means everything that man seeks to acquire, excepting sin and evil), (3) Kama or Sex and Love (where a Man and Woman feel an attraction to each other and lean upon each other for continuing the race, for performing the duties in life, and for attainment of pleasure and happiness) and (4) Moksha or Liberation (from the bonds of Dharma, Artha and Kama, pondering upon the nature of the Supreme or the Reality). Sex is something holy, as holy as Nature or Life, and all Natural Religions recognise its value in life, the need to cultivate it as an essential thing in existence as leading to the Ultimate Reality. Repugnance to Sex is the result of a wrong attitude to life-and the deeper insight of the Phallic Cults offers the only corrective to these aberrations against sex. Here Professor Bhattacharya's book presents a common sense attitude to sex, as a part of Life and Expression.

One thing we notice in this book is the amazing extent of the author's range of studies, In that most important part of the book dealing with the Mother Goddess and the Phallic symbol in creation, we have an almost all- comprehensive treatises on the subject embracing the entire range of religious perception, imagination and experience. No religion, ancient and modern, and no king of popular belief which are exercising the mind and the action of men, has been left untouched, and one must say that one gets bewildered in the midst of this vast jungle of the sex eroticism which has joined forces with religious experience or mysticism. The author has two great languages at his finger-tips-Sanskrit, which he has inherited by tradition and the world of Sanskrit, as well as English. His mother-tongue is Bengali, and these two languages which he handles with such vitality, beauty and force, are, it is remarkable to consider, but acquired languages with him,languages which have almost become like one's inherited mother-tongue. That is why sometimes we find, in his case too, aliquando dromitat bonus Homerus-in his use of Sanskrit and Bengali a rare lapsus calami peeps through his most excellent, almost faultless writing.

I wish I had some more time to give to this vast literary and philosophical creation by Professor Bhattacharya as presented before us. He has been not only a teacher and an educationist, both in theory and practice, but he has been something far greater. He has been a preacher of Religion and the Good Life, of Mystic Understanding and Appreciation. He has taken up the task of guiding a whole section of people along the path of full living and thought in religion. For the last 25 years or more, the forlorn Hindu community settled in far away Guyana and Trinidad in the antipodes of India in the West Indies, religion have found in him a friend, philospher and guide, to help maintain in their souls a touch of the deathless culture and thought of India. This alone has been a work of primordial value, and Professor Bhattacharya unquestionably is a dedicated soul who has felt an inner urge to take up this life of a lay missionary, seeking to bring a spiritual uplift to the neglected children of India in far away America.

I only hope that inspite of the fact that his book might prove to be rather above the heads of the general run of his readers even when they are from India and are highly educated, it will remain a beacon-light of help and guidance for all and sundry. The present reviewer himself believes in at simple faith-the faith of an agnostic who is not an atheist-an agnostic with imagination, for whom a good deal of what passes as profundity and truth in mysticism, owing to his ignorance primarily, is just the blind faith of obscurantism. With this note of scepticism for a mass of mystico-devotional literature, which for the ordinary people would sound as a rigmarole, he still can offer his homage to the scholarship, the talent, the power of exposition and the wonderful all-inclusive erudition of the literary and philosophical genius, as well as worker for the uplift of man-the self-exiled Professor from India in Trinidad, Dr. Brajmadhav Bhattacharya.

SUNITI KUMAR CHATTERJI

National Professor of India in Humanities

Sudharma

16 Hindustan ParkCalcutta 700029

Saivism and the Phallic World is more a book on comparative religion than one exclusively devoted to a remote subject such as Saivism appears to be. In fact, to deal with Saivism is to deal with Hinduism in all its aspects; and to deal with the vexed subject of the worship of sex-organs is to enter into the very complex arena of primitive religions, their traditional cultural forms. Tomes have been written on the latter, but the former has been remaining in the background. There are excellent books on Śaivism written by erudite Hindu scholars and devotees on exclusive aspects of Saivism. This book does not attempt to repeat the performances, neither to add to them.

It really attempts to make a sally into as charged a field of study as sex-worship and erotic frenzy presents; out of a hundred books referring to Śiva worship ninety-nine would equate Śiva, specially Linga worship, with the worship of sex, that is, with phallicism. Not non-Hindu writers alone, even Hindu scholars, specially the historically biased and anthropologically trained minds resort to the convenience of classifying Siva worship as a Sex worship. This is misguiding and erroneous. The truth in it subsists like water in natural milk, or spots in the sun. The sun is sun, milk, milk, because of qualities other than light or water respectively in them. In fact we call a sun a sun, and not think of the spots. In Saivism there lies a profundity that reaches sublimation. Not by sex alone could such a great theme survive through all the thousands of years of human cultural history.

This enquiry leads us to make a thorough study of the subject on the basis of comparative religion. This book has devoted itself to that end.

A book of this nature would be incomplete without the fundamental study of the basic Saivism proper. This has been done in several sections. The associated subjects like Bhakti (religion of adoration and love), the Great Mother and Tantra mysticism, and the metaphysical schools of Hindu thought have also been dealt with.

Because of the scanty resources available in Trinidad on the exceptional nature of the subject, it has not been possible to consult as many sources of reference as the topic would demand, or as the author would have liked to do. But on the whole more emphasis has been laid on the Sanskrit source books than on those secondary research works as the academic studies which reputed scholars have been bringing out from time to time.

Of course, there have been very commendable works done in the past. I regret much to have to say that under the circumstances described I was unable to make use of those great books. I was reminded of W. H. Prescott. He wrote his monumental works on Mexico and Peru without having any knowledge of Spanish, and without having any recourse to the basic records. This gave me courage to pursue in spite of my difficulties. I was lucky, at least, not to have the great historian's physical handicap. I decided not to give up. As far as possible, wherever I have referred to the works consulted, the books and the sources, have been gratefully acknowledged. A special list of References, chapterwise, has been added for this purpose.

A book of this size would have been rendered useless without a detailed Index. Attempt has not been spared to make the Index as complete as possible. It is hoped that readers do find the Index, together with the charts, the diagrams and the photographs, of some use to the proper under- standing of the text.

A number of students has willingly come forward to lighten the haras- sing job of compiling a book of this size. Their enthusiasm has proved to be of significant encouragement in pushing through this task. But the number is too large to mention individually. The author is indeed very happy to thank one and all of these young assistants. He would be failing in his duty, however, if he did not mention a few names in this connection only for the pleasure of associating these dedicated helpers with this book, which for some time had become a part of their individual life. Of these, the name of Mr. Sugrim Gangabissoon comes to the mind first of all. This very heavily committed public servant sacrificed week-ends for months in a row just to arrange the References and go through the entire work from the manuscript to the typing stage. He assisted with his entire family plus an eager and mutual friend, Mr. J. P. Ramsundar, a retired Principal of a Govt. school in Trinidad.

Typing proved to be an arduous task. Even commercial and professional typists found it hard to cope with this kind of manuscript loaded with Sanskrt technical terms. The subject itself proved to be too remote for them to ensure accuracy, and provide some intellectual response. But for the graceful and effective intervention, in this regard, of Mrs. Roberta Muir of the British High Commission, Trinidad, I am sure this book could have been delayed by another two years. Through her friendliness I was fortunate to have secured the valued assistance of Mrs. Claire Diffenthalar, who was responsible for the best part of the typing of manuscript at its penultimate stage. The final typing was professionally done through the financial assistance of a friend. But I record with gratitude the fact that but for the assistance received from Mrs. Muir and Mrs. Diffenthalar the manuscript would never have reached the finalform it did. Apart from these two great friends, I owe much to my humble neighbour Mr. Jawlapersad of Padmore Street who typed more than three chapters out of his friendly considerations. Mrs. Betty Raghunandan Singh, Miss Mohini Singh, Mr. Stanley Blanche Fraser, Mr. Krishna Phagoo, Mrs. Merle Sirju, Mr. Ramcharan and many others who have helped me in preparing the Index and going through the typed manuscript of the text deserve my grateful thanks.

I have the great pleasure of recording my sincere thanks to a team of young hearts but for whose timely appearance and active participation this book might not even see the light of day. I particularly mention Mr. Narine Lall, Mrs. Suruj N. Lall, Mrs Eunice Harbin and Miss Chand Bhagirathi to have taken a very bold step in putting me on the right track, and getting into the execution of what was a very difficult project.

Above all, I owe my sincere thanks to my life companion, my wife, but for whose quiet encouragement and unreserved care and attention, I am sure, I could not have achieved this formidable task.

In collecting the photographs used in this book, I am grateful to the technical assistance rendered by an adored family friend, Dr. A. De, whose skill in the job stems out of his profound respect for the art of photography. The printing of this book at a time when prices of paper and printing are sky-rocketing would have been impossible without the very generous assistance from a good and long-standing friend. It is a pity that I cannot render this altruistic soul a more specific homage than her genuine humility permits me to do.

Lastly, I thank the bunch of young workers at the Oxford & IBH Publishing Company who worked as a team to get this long and technical book printed in record time. I am particularly thankful to the quiet, efficient and dignified Mr. Mohan Primlani without whose sympathetic accommodation and effective steps the book could not have been published in four months. The credit for the presentation and manufacture of the volumes belong to Mr. M. L. Gidwani, Production Manager, who conducted the task of copy preparation and supervised complete production.

August 1975B. BHATTACHARYA

35, Padmore Street

San Fernando

Trinidad

Often I have found my friends wonder at the title of the book Šaivism and the Phallic World.

These friends are not at all otherwise incapable of following intellectual, even abtruse and abstract subjects. They are generally, well-read, and extensively informed. They do understand Siva; they do understand Sex. But 'Saivism and the Phallic World',-what is that? the title appears to have them knocked out.

From this experience I could infer two lessons. One, this subject has to be introduced with great care and preparation. It does not appear to be much 'popular' as a subject, although Siva-worship is the most popular form of worship amongst the largest number of the people of India. But its popularity is only formal; the spirit behind the idea of Śiva, specially the understanding and appreciation of the rationale of Saivism is very rarely cared for.

But so far as Sex is concerned, well, of course every other person seems to be a past master in the subject; at least such is the popular claim. Good. But what about Phallicism? What is that? Adoration of the sex organs. It is shadily known, but is summarily rejected as an obnoxious hang-over from the days of the tribals and the primitives. To pay any sustained and studied attention to this is considered contrary to the run of decency and culture. At least such is, or appears to be, the accepted norm. The subject, though not an utter taboo, is almost always shoo-shooed. Siva is one of the many gods of the Hindus. His worship is a well-known feature. The orthodox and the fanatics indulge in the worship of the Lingam; Sex is also known, because, who pray, does not know it? But to worship that? Ugh: how embarrassing! So we shove it clean under the carpet, and try to look decent. What a burden this 'decency' is to the undercurrents of the mind!

The exposition of such subjects to the people, thus presents utmost difficulty to writers. It is much easier to teach the untaught; but to teach the self-taught is a formidable task. Subjects that people take to be quite familiar, and accept as a matter of fact, often lose their significance for the want of a methodical study and properly educated approach. The familiar is often taken for granted.

Religion is one of those social forms which we have taken for granted. Education of religious forms lacks both in method and thoroughness. Atits best it is handed over as an ancestral and cultural behest. Religious forms and rites are just there to be accepted. Questions are often unwelcome, resented, and even forbidden. Only three things matter: dogma, authority and unquestioned submission. Enquiry is taboo; enlightenment has to be awaited. Thus, religion, which confers the sublimest of liberation, itself suffers from the lack of it.

We could cite an entire range of subjects to illustrate our point. Well-informed as we claim to be, we neglect a good part of the most valuable heritage of our life and culture, because we happen to inherit them automatically, without much effort on our part. We fail to be convinced of those gains which we are made heir to, since the gains are not immediately recognisable, neither earned through personal labour.

It is not because there is something inherently wrong with the religious amongst us, or with religions as such, that these are resented by the intellectuals. This negative escapist attitudinous approach makes them take pride in remaining ignorant of a very highly attractive, and inescapably involving facet of the human society. This resentment, which has kept us defiantly away from a vitally important engagement of life, is bad enough; but what is worse is that more often than not we are grievously and unreasonably prejudiced about it. Religion has been one of the most inspiring subjects to millions of mankind from the dawn of human culture; it has crystallised society and social forms, and contributed much to the consolations of those mysteries from which the agonised soul of man has derived an unfailing and sustaining consolation, received an urge to live, obtained a fresh lease of hope.

In every country and climate religion has taken its special form. Like the sun, the moon, the stars, air, fire, water, soil, rivers, sex which have been universally adored, certain forms too have been universally adored and cherished. The idea of Siva evolved one such form, and is thus taken for granted, which is just an euphemism for being utterly neglected. Śiva is indeed a dear god. But when one mentions Saivism, upshoots a frown. What is that? How does it concern us? Śiva we like. He, a hail fellow well met, enjoys drugs, drinks, and dances, and runs about in the nude. Quite a liberated soul. Let him remain in the temples. Mother looks after his little needs. We too pay our attention to him when fate presses, or at our convenience on special days. The attitude does not differ from paying a visit to the doctor's chamber, or to the bank-manager. We have gods and gods; temples and temples. How do they concern any more? Then what is this Saivism? What is the point of making a study of it? Some gods are obviously understood. Some we do not, and dis- pose of as 'mysterious', 'esoteric', etc. We remain alien to our treasures, blind to our needs. We remain famished in spirit, and our hunger for fulfilment remains unsatiated. By victimising our faith, we ourselvesperish as victims of our ill-nursed ego. Modernism has given us the ennui of cynicism. Religiosity, by and large, is sneered at as a sign of backwardness, and acceptance of gods automatically exiles a person of taste from the haloed circle of progressive intellectuals. Actually our gods definitely suffer from a disfavour from the 'educated', whose only title to sneer at such knowledge springs from their ignorance of the subject.

These too take these ideas for granted. They view religion and religious establishments from a sociological and economic stand-point alone. Their dialectics spin around the uses or the misuses that certain individuals, or classes, have made of religiosity through self-styled authorities and diehard establishments through dogmatic pontifications, or fantastic reactions. Individuals and establishments have misused orders of society. They let loose malice, encouraged hatred, participated in blood-baths, ran hand in gloves with imperialistic designs, shared in denuding countries, peoples, cultures. They are still at it. The ways of sin are subtle and dark; those of virtue are tender and open as the gifts of the sun. Time has punished them by bringing in drastic retributions. But that which is essentially beneficial to the cultivation of peace cannot be abandoned through the misdeeds of a greedy force. We know certain forms of govern- ment to be bad. We have a right to change them, and have a good government. But for the sins of one pattern of government the institution of government cannot be done away with. To write off establishments for bringing in redress to the exploited and the suffering, the deluded and the handicapped is to create a dangerous vacuum. Such vacuums in history have at times ushered in, through the backdoor, such mystic rites and practices as have proved to be dearly dangerous to the mind and body of both individuals and cultures. Man will always need to follow a religion. If he rejects the old, a new religion will come up, and hold him under its spell. If old gods die, new gods will crop up. Even iconoclasts follow and shape a religion. Those who reject all religions, follow a zeal, and make themselves fanatical followers of a novel religion. Man cannot do without some faith that relates his inner personality with his outer existence.

The answer to this dilemma is to understand the necessity for the human soul of such a quiet parking place as religion, whereby the inner person in the man could wash, repair, iron out the dirts and the rumpled creezes of his own doubts, agonies and sufferings. Religion fulfills a spiritual need; form of government satisfies our material needs. The relation between material and spiritual needs is a mysterious one, beyond the ken of regimentation. It would be highly unfair, prejudicial and regressive to condemn an entire system, because of the criminal exploitation of a situation by some cynical individual. Bad priests corrupt good religions; as power corrupts the sense of equity, or bad teachers, goodstudents. It would be highly unfair to let 'gods' suffer because of such transgressing humans, and their petty foibles. Let men think to love, and love to think.

Where there is no love for the subject, there is no worship for an Idea. Any god, to be true and functional must first find place in the heart; and an Idea, to be functional must be fully understood and appreciated. When we love, or make love even with our opposite sex-partners, but lack in a full rapport or understanding, the love remains only skin-deep and functional, but fails to grow roots. Thus a merely educated approach to the understanding of the divine is, generally speaking, lack-lustre, lackadaisical and cynically disposed. God worship has become to these a part of superstition. We are, thus, trying to condemn a subject because of the fact that some indiscriminate self-seeking rogues have been misusing and exploiting a situation for personal gains and advantages. Are we justified in condemning medicine and the medical science because of the unscrupulous behaviour of some of the professional rogues who are a disgrace to a noble and important profession?

Apart from this lack of information, and what is more concerning, this cynical attitude of considering the familiar as not worthy of study and enquiry, the subject remains very remote to the common man who thinks that all that is sex is either obscene, or viciously exciting. This brings me to the second lesson I have learnt. The fact is that Sex is an unavoid- ably serious subject. In fact it is the most dominating power in life's progress and activities. This book I am writing, these lines I am typing on my machine, the joy I am deriving from a special turn of phrase which successfully projects my ideas, contribute to the healthy functioning of my libido which is so very important for my faith in life and living; and then through me it becomes so very important to those hundreds of persons who have to come in contact with me daily and nightly. My ego, my libido, my social identity and contribution are inextricably inter- twined. But we ignore the fact that all expressions are functions of this libido. Sex is a Power supreme; and the ancients had recognised it as the Lhadini-Sakti, the ecstatic power of the Mother; that mysterious chained reactions which generate, nurse and reproduce life and all that life functions through. To worship this power, to understand and love and bring homage to it is the birthright of the developed man, nay, if possible, of the developing man as well.

Since we do not care for the one as too familiar, or for the other as too embarrassing, the subject of the book remains unfamiliar. Unfamiliar, but not unnecessary. It is the most necessary subject. It is absolutely necessary for man to know what debts he owes to him-self, to the Life he enjoys, to the Life that surrounds him and keeps him covered from all sides: the life in the air, in the sky, in light, in rains, in the soil, in thewaves, in the rivers, in the greens, in colours, nay, even in fears and loves, in doubts and images, in dreams and aspirations, in all the aspects, all the facets of this most fantastic and splendid of miracles, the miracle of Life. We must know what we owe to it; what it owes to us; where is this commerce transacted, and what are the rules of the game. Could we remain blindfolded in the race of Life, and still hope to reach the appointed goal; or should we strive and prepare, and get ready to shape our own destiny and wrest the initiative from a merry-go-round, spun by some unseen power?

This is the challenge. This is the subject of this book. Saivism is the subject of understanding that Power which remains unmanifest in spirit and form, but expresses itself in the millions of aspects of life's manifestations. This Power of manifestation and dissolution is called Siva-Sakti, the Time, the Energy, the grand play of Communion- manifestation-maturity-disintegration-annihilation-turning again to flux, and coming to manifestation yet again. It is a complete circle; and this cyclic movement, within which has been preserved Life's well- being, is called Śiva. The ancient farmers had visualised this process in the life and death of a sheaf of barley; the sage visualises it in his meditation. The former founded religion and prayers, the latter gave us metaphysics and knowledge. To worship it, to bring homage to it, after understanding its ways and approaches, is Saivism.

This is the Siva that the Hindu has been adoring from times immemorial. Yogis have sat at its feet. Sages have sung of it; lovers have shaped it into form, and raised monuments of love around it; metaphysicians and psychologists have rationalised it, and tempered it with form, discipline, attitude and rites. This entire 'world' of Saivism is engaged to the research into the unfathomed depths of the Soul's hunger for a supreme delight. If reaching the top of the world is filled with excitement, and rewarded with glory, then it must be much more rewarding indeed to try to reach the apex of all human ideals, the Source of all Joy. This is Saivism, an adventure, and a fulfilment.

But Phallicism is different. It is the worship of the sex organs as organs, as instruments of a function which mysteriously draws the two opposite forces together and participates in an act which is supposed to contribute to the biological life its highest sensuous excitement and thrill. In many cases of living organisms this thrill is sought for and consummated at the cost of life itself. Such is its power and driving force. For achieving this thrill all life, animals, insects, birds, reptiles, risk supreme sacrifice. Danger does not deter; disease does not threaten; law does not stop the response to this call. The cruelest of punishments, the highest stakes of peace and tranquillity have been squandered for the achievement of this thrill through union.

What are the secrets of this Power? Like all mystery it has its magnetic magic influence over good sense. It spreads a net to confuse, confound and stake desperate bids. Yet it shapes, forms, creates. In order to use it properly one has to understand it; and then adore it in the way it has to be adored. This adoration of the mystery of the sex-power has been called by the anthropologists as phallic worship; and the science of understanding the secrets of this power, and of properly realising the extent and range of this power is called phallicism.

Attempt has been made in this book to make a comparative study of these two forces. The one is often mistaken for the other. It has been having for a very long time an extremely raw deal, which has to be set right. I do not know how far I have succeeded in setting this right; but I know that I have tried most sincerely and to the best of my limited ability. All I need, and would beg for is the reader's kind patience, and scholarly tolerance. If the reader's painstaking journey through the book renders him in anyway the abler to face these problems, and the general problem of life, I, as a fellow traveller, shall find my troubles amply rewarded. I seek the reader's co-operation.

The nature of the subject makes it essentially imperative that the treat- ment should follow the method of studying a course of comparative religion. The records of most of the human cultures had to be taken into account in order to discover some form of a common pattern along which the human world has faced these problems. There was no time when in human society the mystery of life was not found to be entirely fascinating, or when this fascination failed to draw a reciprocal tribute from grateful, but equally amazed souls. This is due to the yet unexplained sense of the mystical which in all sensitive minds works insistently. The world of mysticism is as old as the skies; and to this world of mysticism we are all being drawn inscrutably, inevitably even through the various forms of our religious differences. The future of religion has to find its maturity and finality in the realisation of that unbodied joy which mysticism nurses with care and profundity.

The primitive and the modern are knitted together by certain fundamental basic ties. All that is fundamental in spiritual realisation stands clear of the Time-dimension. Fundamental mystic wonder and enquiry transcends Time. From the dawn of human history the wonderment that is Life, that is Sex, has never ceased to demand man's absorbing interest. Worship is but an expression of that feeling of gratitude which the human soul bears to this abiding sense of mystery in the evolution of Life from Life. Worship is, as it were, an investment for hope and success, the two driving tonics which keep life on the run, despite its many failures and disappointments. It is a form of humble submission to forces of a higher order. If such is the case, to bring homage and tributeto this great Power of Life was, and is to be, accepted as a natural ex- pression of the natural Man. Through accepting this, Man elevates his inner personality, and achieves liberation, along with its sublime gift, namely, joy.

Later thinkers have reasoned into the human pattern of behaviour, and laid down metaphysical and psychological laws with a view to rationalise the unbroken consistency of that behaviour. The human society is as extensive and as varied as patterns of the life on earth are. This society in the course of its development has come under a variety of influences, e.g., climate, geography, food habits, etc. The influences and their differences have, to a very large extent, conducted the defences of the social forms and norms, which in their turn have influenced their pattern of worship. These forms differ as the climatic and other external influences do. This is the reason why when the human aspirations, de- mands, difficulties, challenges, etc. remain constant in all parts of the globe, the nature of religious forms, of spiritual doubts-in other words, of gods and goddesses, spirits and gnomes also differ. They do differ; but fundamentally the problems refer to the same inspirational modes: food and security. Human society is crowded with many gods, many religions, many forms of authority conducting the gods, and the mechanics of handling them. In spite of it all God is one, and that special feeling, best described as a craving for the ultimate in joy 'the devotion to some- thing afar' is also universal. Only the forms differ. A study into this anthropological characteristic of human behaviour which concerns the area of the spiritual, or the mystical, leads us to the fascinating and very rewarding study of comparative religion.

It was an unfortunate day when European conquistadors, and adventurers appeared on the other continents, and quickly brought to the blocks very ancient cultures under different excuses like religious expansion, cultural education, political emancipation, etc. The actual design was, however, undue criminal exploitation under the support of imperialism and capitalism. Religion was cited as one of the many justifications for this type of indiscriminate denudation of human and economic material. Those religions which did not conform to the ideals of the occupying forces were rejected, at times with the assistance of sword and fire; and derided with impunity, when necessary, with the help of pseudo-intellectual scholarship and faked authority. The theory of the superior race was yet another imperialistic projection. No one found it profitable to make enquiries into the spiritual greatness of these suffering cultures through a dispassionately just vision, which a student of comparative religion alone could achieve.

Days have changed. A host of scholars are today working on the subject of evaluating the contributions of the different religions which havesupplied to nations and cultures the spiritual food they needed. With the growth of the democratic rights of the people, with the rejection of the claims of the imperialistic orders of society, specially since the Second World War, this branch of human studies has restored to a very great degree that confidence in human mind which has made it possible for aliens to have respect for the creed of others. But for this latest adventure into the realms of philosophy, religion and anthropology, this work could neither have been dared, nor presented.

In making this study as complete as possible the author has tried his best to present similar facets of religious and metaphysical ideas appearing in sister cultures, whether ancient or modern. Starting from Sumer and Egypt our study has gone through the Greek and Roman times, covering in between the cultures that flourished in the Mediterranean and the Oriental regions. Of course, the Aryan and the Iranian cultures have finally emerged with a greater emphasis. This was so because the subject relates to the worship of the human organs, the source of Life, otherwise known as Phallicism. The Hindus adore Śiva as an Idea, a sublime source of spiritual and transcendental inspiration. But for certain external similarities the worship of the Hindu Idea of Śiva (Saivism) has been rudely identified with the primitive and the Oriental phallic worship. Although the different cultures and religions have been studied, the principal theme, that runs through it is a study of Saivism in contradistinction to Phallicism which runs through the whole of human history. This has brought us face to face with Tantric mysticism.

The subject is not at all an easy one. The sudden upsurge of a variety of books and writings dealing with sex-worship, and the worship of various types of god-forsaken aberrations muddles up further our attempt to keep our discussion clear of this mad popular hunt for excitements, miracle- men and instant liberation. We are itching for holding on to a justification for pursuing a ruinous way in the name of religion and scholarship. By its own genius and nature the subject has to be one which keeps away from saucy popularity. It not only encourages mysticism, but also faces the danger of falling into the trap of obscurantism. When we have to deal with such forms of spiritual practice as the Lamaic Tantra and the Hindu Mystical rites, we could hardly avoid being obscure to the uninitiated. While dealing with the basic rationale of Saivism and different forms, we had to deal with the Systems of Hindu Thought, and the Systems of Saivism. More often than not these abstract and subjective discussions face the charge of speculation. But one might concede that in the nature of the subject certain abstractions, both of language and form, were inevitable. These difficulties have not been particularly solved by the language difficulties of one whose mother tongue is not English, and who realises the bitter fact that English is not the most equipped language forconveying the highly metaphysical ideas and nuances of Hindu meta- physics. Most of the terms, the technical words, thus, have been left in their original Sanskrt form, although translations have been attempted.

With a view to making the presentation as authentic as possible direct references to source-books have been made. References have also been made to the scores of later authorities of scholars who have worked on the subject and allied ideas. Those who actually speak from experience use a simple and direct language. These are the persons whose language bear the stamp of authority. Their language cannot be compared with book-workers, and men of mere secondary knowledge. The flashes of experience which have from time to time graced the present author have however aided him immensely in daring to speak of things never spoken before, and in a manner which, so far, he has missed in most of the western authors, except a very few. But how little is that in comparison with the vast scope of the subject. Simplicity and directness are divine gifts of experience of the Supreme.

The subject itself was difficult: a comparison between Sex-worship, and the worship of Siva. In dealing with it I had to dive deep into the former, and contemplate and meditate on the latter. Whilst Śiva has been kind enough to guide me all the time with His Grace and Light, the study of the adoration of sex has again and again taken me into deeper and deeper waters. This is a quicksand-subject for any scholar to fall in. Once stepped into this mystical area, the enquirer finds himself engulfed by an unseen pull that sucks all his personal control until all Time-Space bearings are taken away. It is my considered advice to those who should ever attempt to dive into the unfathomable chimera of the subject of phallicism, who dare to be sported away by the hope-raising mirage of an otherwise ever-thirsty expanse of limitless mystery, to stay away from the captivating, ensnaring light-dances of the mystical White Goddess. The study of the adoration of Sex is a study that leads to the banks of the legendary Lethe, or to the cells of the shady Bedlam. The enlightenment men seek from the study of this captivating, engrossing, absorbing study makes him search till doomsday for the lost shell on the vast, howling shores of life.

For twelve years I have been in search of the answer. The riddle gets more confusing and more confused; yet the challenge bemuses, and even transcends all fears and risks. Both angels and fools become one in this stride. Twelve years of scouring through these subterranean mines have not made me the wiser. I have sojourned through Sumer, Babylon, Egypt, Greece, Crete, Iran and the mountains of the Asia Minor and the Himalayas; I have known of the Sumerians, the Akkads and the Myceneans, the Phoenicians and the Phrygians; I have gone into the stranger realms of the mysticism of the African tribes and the Sufis, justto hit upon the answer why this fascination for the adoration of Sex, and why this quest for some sublime delight in the area of the Mind; why the quest for the Still Poise 'of the lamp's flame in a windless vista of the Spirit'?

In the course of this sojourn I have met with strange gods, goddesses and their stranger behaviours, as well as the rites that supposedly claim to assuage their destructive fury. I have met with such gods as Ba'al, Marduk, Atys, Adonis, Mithra, Zeus, Jehova, and such goddesses as Astarte, Kouretes, Isis, Cybele, Kali, Aphrodite, Diana, Tara, Esther, Sarasvati, Camunda and Chinnamasta. Many of these have been destroyed by human sword and fire, only to rise again from their ashes amongst other peoples, in other countries, and with other names. Gods that emerge from the mysterious ocean of cults prove their immortality by never dying, and by ever resurrecting themselves from their dead and cold tombs. We, perhaps, could establish a new religion as Pythagoras, or Calligula, or Julian or Mani did, and laugh at the old ones; but we are destined to confront the brutal discovery that no god is ever born without owning an ancestor before him. The latest of the religions has links with the oldest. This ultimately makes me aware of the rewarding truth that not only God is One, but Man is One too.

Throughout this book my mind was focussed but on a single point; but it had to cut through a wilderness of critical questions. The journey has not been an easy one. Whence was this Phallic? How did it captivate Man's sublime adoration? Was it an accident?-A matter of choice? -A natural expression?-A divinised mysticism?-An invention of rascality? A scandalous self-projection? Or, is it a natural expression of the most irresistible, instinctive and intimate urge of life of Man in particular? If the phallic has ever been divinised, in which form or forms did the divinity present itself, and with what rites? Did the divinity of old really indulge in Sex and Sex alone as in the Alexandrine temple of Aphrodite, on the shores of the sea at Paphos, or in the Babylonian Ziggurats of Marduk and Ba'al? Was the adored Sex-sacrifice based on and doused with orgiastic abuses? How far, then, were the temple- dancers in South India influenced by these Persian Gulf practices, and how far these 'virgins' survive in the vestal virgins of Rome, and the Christian nuns of today? Did the so-called sex abuses contribute to the disintegration of some of the ancient civilisations, or are the disintegrations traceable to entirely economic, social and political causes? Did the religion, known as Christianity which was born out of the ashes of the ancient religions and the Semetic indoctrinations, borrow from the old rites for keeping its hold on the masses? How much did it owe to Mithraism, Manichaeism and Buddhism? How came the later gods? Were the Hindu gods entirely Hindu? Did the process of the mysticDhyana alone produce the many gods, or were the gods projected by exist- ing gods destroyed by human hands? What made the gods travel from one culture to another and demand contrary types of homage?

Thus the origin of religions, their relations with cults, perpetuity of the cult-forms in religious rites had to be discussed before a step could be taken carefully into the hazardous area of the relation between phallicism, and the later growth of the sublime Idea of Saivism, which is a thing apart, as Man is from the Ape, as the cave paintings of Brittany are from the wonders of Valesquez, Matisse and A. N. Tagore.

The search for the roots of the phallic rites eventually guided me into the burning quest for a rationale, i.e. the spiritual, even an intellectual basis for finding out a relation between Matter and Energy, Power and Consciousness, Śiva and Sakti. I could feel that in finding out and establishing that relation it would be easier to find out the relation between the phallic and the Sublime; between the immediate Life-Force and the Sublime Spirit, which unseen behind all forces, moves without moving, comes nearer without changing places, loves without having to feel, and 'is' without having to be. It becomes a becoming when understood. It transcends Life when Realised. This transcendentalism of the Matter going into the search of the Spirit, of Joy into that of ecstasy, of the limits of sufficiency into that of the liberation, of the Infinite of the overflowing Immense, enraptures and binds, spells, charms and enslaves. No; no man should get entrapped into this snare of probing into the limits of the Sex-urge, the Limits of the Life-force, of the Lhädini, of the Libido,-the limits of this Fiery Lingam. It has been forbidden in the Sastras again and again.

I. I had first to probe into the earliest instincts of Man, such as Hunger, Fear and Self-protection, Sex and Propagation, Wonderment and Enquiry. I had to find out how the honour and the glory for having patterned the infant society of the Homo Sapiens into a Culture, and then into a civilisation must go to the females, the Woman, the Eternal Virgin, and not to the Man, the usurper, the tyrant and the selfish militant diplomat. I had to watch with amazement how the roots of the much glorified modern progress (sic) of society actually lay deep into the antiquities of the skill and sacrifices of the Mother, the Eternal Virgin.

II. It was she, who, out of the serious business of life's pains and pleasures, of life's needs and fulfilment imaged her own self; and it was but natural for her to image herself in the spirit and form of the female, the one who under the maddening heat and urge of seeking the seed of propagation is ever and ever in search of drawing the life-sap from the wandering, roaming, care-free male. She wanted the male to merge into her; die in her to be reborn. She loved and adored him only to drawhis life-sap, and hand the same life over to another cycle of birth and death. Nature, the Virgin, sought the germ of the Sun.

Cultures grew out of this homage; this imaged pattern. Monuments were raised; rituals prescribed; ritualists specially appointed; the death of the male in the female as an evolute of the laws of cosmic creation had to be adjudged, perceived and expounded against the trend of the ancient pagan religions and their modern and sophisticated counterparts. From this crude blunt life and its expression, adoration entered into the area of refined, sophisticated implications and interpretations.

Of these evolutes were later gods made. These gods were the necessary growths from the projections of the primitive human mind and its different aspirations. Nature-gods, totems, taboos, symbols, myths, sacrifices, religious processions, religious assemblages and celebrations evolved out of this. The mystic and cumbrous tracts left by these practices demanded further analysis. It was found that the initiative of the importance of power of both Sex and Life on the one hand, and of Good and Plenty on the other, propelled throughout the progress of the history of Man in every country, at every time, amongst every people and culture, modern or ancient.

Having thus taken ourselves through the crowd of the gods of the ancient people we gradually become aware of the fact that in the world of religious thinking and spiritual aspirations two postulates claim our attention the most. One, Man was in need of joy; and two, Man was also in need of food, protection and power for assuring security. In this search, he found that the Idea of having a Mother-deity, a Mother- spirit alone could fill up all that he sought as his emotional and practical fulfilment. There was a universal Mother. This Mother, the White Goddess, the Eternal Virgin, the Lion-riding Mountain-Maid became the central spiritual attraction to the millions of adorers who needed a support for raising, and thereby revealing, the innermost aspirations of their soul and body. This was the Mother.

III. The Mother has been universally adored, and mostly so in the Ancient East. Hundreds of expressions of the Mother in symbols, in terracottas, in statuettes and monoliths, myths and monuments, and above all mythical compilations of Tantras and Puranas of the nation are today available for study and scrutiny. In fact, no modern civilisation, no modern religion could claim a growth free entirely from these lores and myths of the Great Mother. Much of the rites associated with the Mother has been pushed back into the darkest of chambers of mysticism. Much of the chants and prayers today are shrouded in unintelligible mystic sounds. Much of the rites have been persisting under completely changed and misleading forms;-but the Mother continues uninterrupted. The tribes, the roving Aryans, the proto-austroloid natives of the oldworld, all had their own Mother: Umu, Ummu, Amma, Umā, Ambikā, Cybele, Kouretes, Astarte, Kali, Isis, Esther, Tara and Sarasvati.

From this came the half magical, half-mystical codes of ritualism known as Tantra, most or all of which are still found in the Atharva Veda. A rite, Factura, Kytyä, Kriya, Zauber, Tanyan meant to do something; to secure health to the body, or plenty to the fields, or ruins to adversaries. The Mother has been sustaining and preserving.

The Mother was accepted by the Aryans side by side with the Father- god Symbolic to this acceptance Fire, as a form of the Mother, was also accepted by the side of the Fire-god who sought only virgins. Around Fire a thousand myths arose. Schisms and counter-schisms set apart the history of cultural developments. One society alone sprung a hundred leaks; and the legends, to this day, preserve the glories and the incarcerations of those conflicts leading to a thousand struggles, not all of which were free from severe blood baths.

IV. Soon this paganism had to give way to systematised thinking; rationalisation had to be faced sooner or later. This has been the greatest achievement of what Karl Jasper calls the Axial Era. In China, Greece, India, even Arabia and Persia great metaphysicians and logicians, through the media of mathematics, logic, astronomy and metaphysics systematised man's attitude to the divine.

The Hindus called it the Laws of Insight, or Daršana Sastra. Hindu thinking as distinguished from the Aryan, or Vedic thinking organised around the 'six Systems'. These six Systems had to be studied and mastered, without which the polytheism of the Hindus would ever and ever remain a maze of confusion to all, inclusive of the Hindus themselves. India, where alone Hinduism is practised today without having to change its name or tenets, has been responsible for the propagation of these six Systems. Because the Hindu takes these Systems for granted, he does not, generally bother to come to any closer grips with the contents of the Systems. As a result the average Hindu accepts his many Gods as a multiplicity, with the same ease and relaxation as he faces the mounting population of his country. In the teeming tropics covered with primordial forests and cloud-brushing mountains, multiplicity of the one is accepted as a matter of course. Yet, the same thinking Hindu, on the other hand, based on these systems, accepts polytheism with a tongue in the cheek, keeping himself all the while fully alive to the dramas (Lila) of what these strange forms mean metaphysically and ritualistically. Hindu polytheism is an interesting subject, and has been separately studied even before the study of monotheism, and especially of Saivism.

We have started the study of polytheism with the Vedic gods. After this most essential study, we have tried to connect the Vedic gods with the Aryan gods in Greece, Rome and Egypt; we have also attempted to markout two clear divisions: (1) cultures and civilisations predominantly accept- ing the Mother, and practising, what has been termed in our study, Tantra, and (2) cultures and civilisations which accept a Father-god, principally practising such rites around the Fire, which has been called a Male god, and substantiates the virility of the Male. The incorporation of the fire- rites of the various peoples of the ancient world into the adoration of the Vedic fire is an engrossing study.

V. Then came the time when, in India, due to various factors the peoples from contiguous areas began to pour in large numbers, and settle. It became necessary for the homogeneous Vedic forms and non-Vedic cults to get organised before the inevitable law of syncretism operated, and pushed the age-sanctioned and sanctified Vedic forms to get almost completely lost. Out of this phenomenal movement of the large human cargo evolved the wonderful literature known as the Puranas; the sublime tradition known as Bhakti; and a supreme concept of a Godhead, the god of all the gods, Devadeva, Mahadeva, Šiva. Śaivism was the ultimate of that process which had started with the phallic and the tribal, with the Ganas and the Siddhas, fire and sacrifice, Tantra and Siddhanta, Vedic Homa and Tantric Abhicära. Peculiar to the glory of the accommodating spirit of the Indian mind the differing Systems were allowed to be superseded by enforced religions; many trends and many rites, some Vedic, some non-Vedic, continued to exist and wait their own destined extinction either as individual religions, or as one merged into the mainstream of Hinduism.

The philosophy of Bhakti gave way to the growth of Vaisnavism, Šaivism and the age-old Tantricism. To the mainstream of the Puranas the various lores, legends and rites brought their own tributes until the great stream of the Hindu thought ran vigorously through the Time honoured land of India. The system was known as the system of Vyasa, who had collected and compiled the scattered knowledge, known as the Vedas. It was a method to synthesise a scattering and scattered heritage. It was the Vyasa heritage, the Vedic heritage. The Puranas were its last attempts, and, as they proved to be, a very abiding attempt, for sustaining and crystallising the main Hindu body into one monolithic tower of strength. The immortal Bhagavat Gitä evolved out of this very method of compilation.

VI. As the second abiding gift of this synthesising method we received the Saiva Siddhantas, in which Vedantic Monism, Tantric Empiricism and mysticism, Vaisnava Bhakti, Jaina and Bauddha schisms (in favour of an experimentation with a godless formless code of good conduct, based on a moral living and a spiritual elevation) combine together. The Siddhantas, especially the Trika of Kashmir, charged with the Tantric nuances of mysticism, has remained a monument of the spiritof Hindu accommodation. The Saiva Siddhanta of the south of India on the other hand has accommodated the various factors which challenged the Southern life-rhythm over the centuries. It developed into an emo- tionally inspired system of dualistic monism, of which Love and Faith are accepted as the two principal wings. The study of this dualistic monism has remained an adorable and fascinating exercise for students of Hindu thoughts. Pure monism takes to the study of the theories of Pratyabhijña and Spanda, Advaita and Viiisfadvaita on the one hand, and of Sthala and Sakti on the other.

This is not all about Saivism. There are numerous other Minor sects of Tantra and Saivism, such as the Näthas, the Siddhas, the Maheśvaras, the Vaikhanasas and the Pasupatas. No study of Saivism could be deemed complete without these part-occult, part-mystic sects, mostly held in suspect by the orthodox. What we call Śaivism, in spite of its having very close, but obvious resemblances with the erotic and the phallic, has been in fact and practice, for the pious Hindus, a symbol of purism, of the ethereal sublimation of the idea of Saccidanandam of the Upanisads; and incidentally this has become the final abode of the conflicting rites of those aliens who from time to time had taken shelter in India. In Saivism we find the traces of the ancient religions of the countries and civilisations which flourished over fifty to sixty centuries around the Arabic part of the Indian Ocean, inclusive of the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea and the all important Mediterranean Sea. The study of Saivism, in this light, has thus compelled us to ransack partly, the history of human movements during these centuries, and the study of the myths and lores of all the gods and goddesses who came to live and die in the ancient, pagan, Greek and Roman worlds. Hinduism is the only religion into which these forgotten religions still find a place; and their mystic murmurs are still heard in the Tantric and Saivic practices and chants. Some of these charms and prayers have been appended.

VII. This has compelled us to dive into the myths. If attempt has been made to interpret these myths, it was only to illustrate the fact that the legends are but the wombs in which seeds of historical facts germinate and await the light of understanding. To connect myths with facts of history, as well as the deductions of metaphysics, is to reach the ultimate in scholarship. Distinguished scholars have attempted the task. Others shall yet come and continue doing it; for the field is vast; and life is too short for only one man to do it all. The little that has been at- tempted here might serve to inspire the inquirer to gain a peep into this yet undisturbed pyramid of lores, so that the wealth of the treasures could make a future Champollion accept the challenge of discovering it further and thoroughly.

VIII. Finally, I thought that a subject like Saivism calls for an insightinto the nature and ideals of Hindu art generally and of Hindu images in particular. The relation of the divine transcendental trance, the inducement of mind to get relaxed into cosmic expanse of Immensity and the thrill of the Time-Space converge into the image of Siva, together calls for the adoption of symbols, Mudras, Yantras, etc. which are held to be very purposive to the aim of concentration. In fact, all treatises on Yoga inclusive of Patanjali's famed Yoga Sutra, prescribe adoption of such images, within which the image of 'sound' has also been discussed. Sound as a cosmic expression gives us the mysticism of the Mantras, the chants, the prayers and the hymns. Music as a source of divine expression has been recommended in the classic Hindu books on the subject. Even the ancients and prehistoric cultures sang hymns.

We have attempted to explain the Siva icons, images and the Lingam in particular. We have given some data regarding the famous places of Šaivic pilgrimages, the Siva-sanctuaries, the details regarding the Saivic rites, and the significance of the objects, inclusive of the flora used for the Siva-worship. This covers the vexed subjects of Yogic trance and the use of drugs.

I am not sure how far I have been able to complete the task I had been called upon to undertake. I also do not know how far my researches would satisfy the scholars in the field who have produced more thorough works on sections of the subject. I have not seen so far any work which deals with this subject of a comparison of the Saiva philosophy with the phallicism practised by all cultures, Eastern or Western, specially the phallicism which has been so popular in the Orient of the ancient times, and the influence of which is still very prominently traceable to the practised religions of the West. Only the Hindus have contained that instinctively inspired strain within the bounds of rationality, and sub- limated the instinct through a religious practice of which Śiva is the Supreme Ideal godhead epitomising the monistic concept of Satyam, Sivam, Sundaram (the Real, the Still, the Beautiful). After all does not Šiva, the equaliser, the assimilator of the legends drink the poison of malice and greed which once had threatened the very existence of creation?

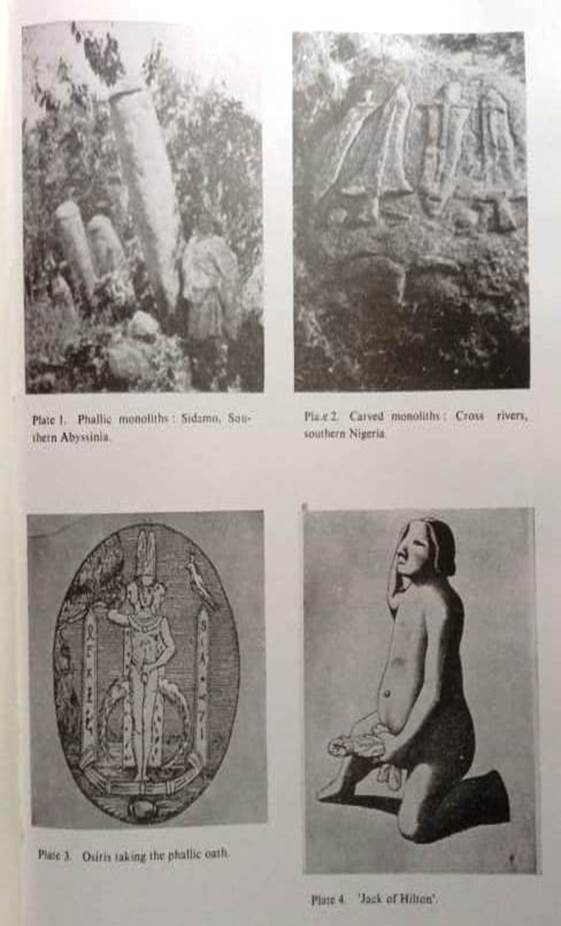

Plate 1. Phallic monoliths: Sidamo, southern Abyssinia (From "The Encyclopaedia Britannica", XIV edn., p. 304, pl. 1)

Plate 2. Carved monoliths: Cross river, southern Nigeria (Ibid., pl. 3)

Plate 3. Osiris taking the phallic oath (From "Phallic Worship" by George Ryley Scott, p. 315)

Plate 4. Jack of Hilton' (From Plot's "Natural History of Stafford- shire-1786")

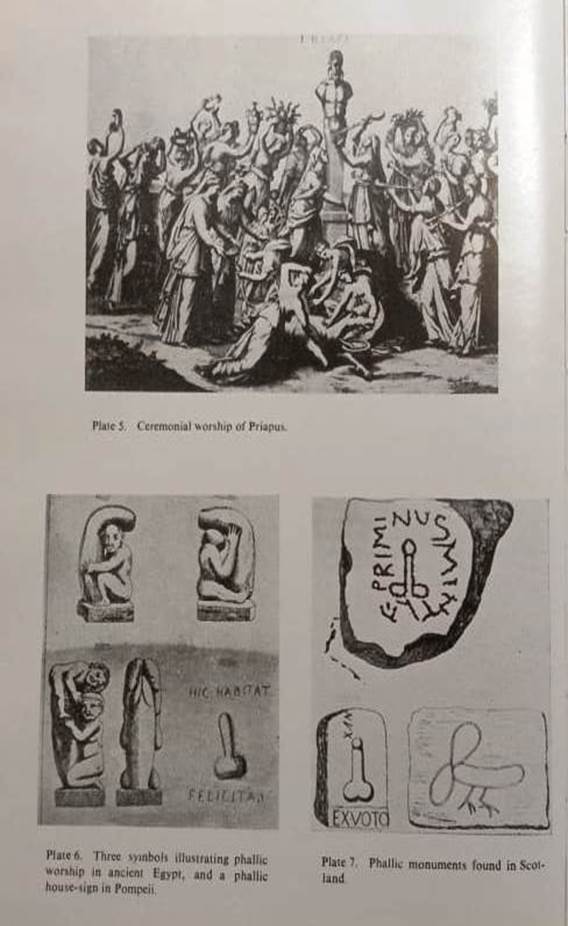

Plate 5. Ceremonial worship of Priapus (From "Phallic Worship" by George Ryley Scott, pp. 128-29)

Plate 6. Three symbols illustrating phallic worship in ancient Egypt, and a phallic house-sign in Pompeii (Ibid., pp. 128-29)

Plate 7. Phallic monuments found in Scotland (From "Sexual Symbol- ism" by Knight and Wright, p. 23, pl. +, fig. 1)

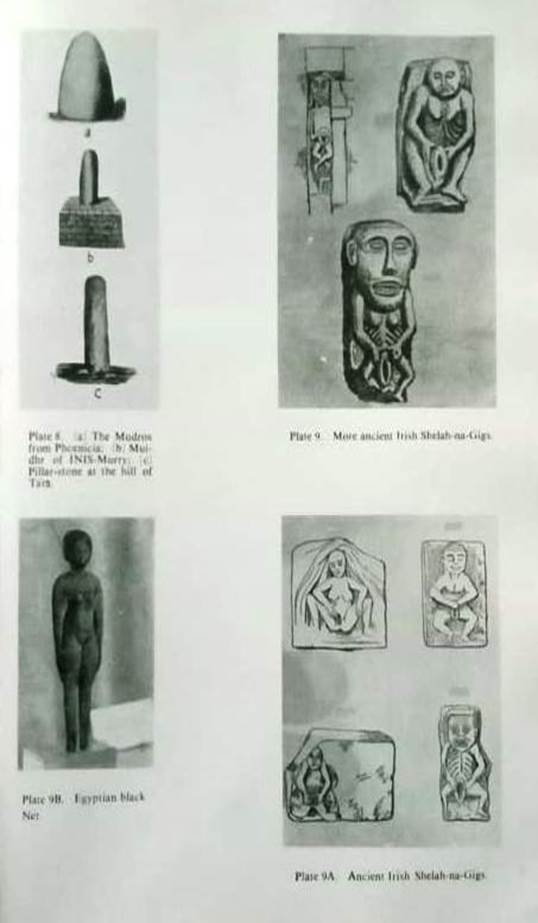

Plate 8. (a) The Mudros from Phoenicia; (b) Muidhr of INIS-Murry; (c) Pillar-stone at the hill of Tara (From "Towers and Temples of Ancient Ireland" by Kene)

Plate 9. More ancient Irish Shelah-na-Gigs (From "Phallic Worship" by George Ryley Scott, pp. 207-208)

Plate 9A. Ancient Irish Shelah-na-Gigs (Ibid., pp. 207-208)

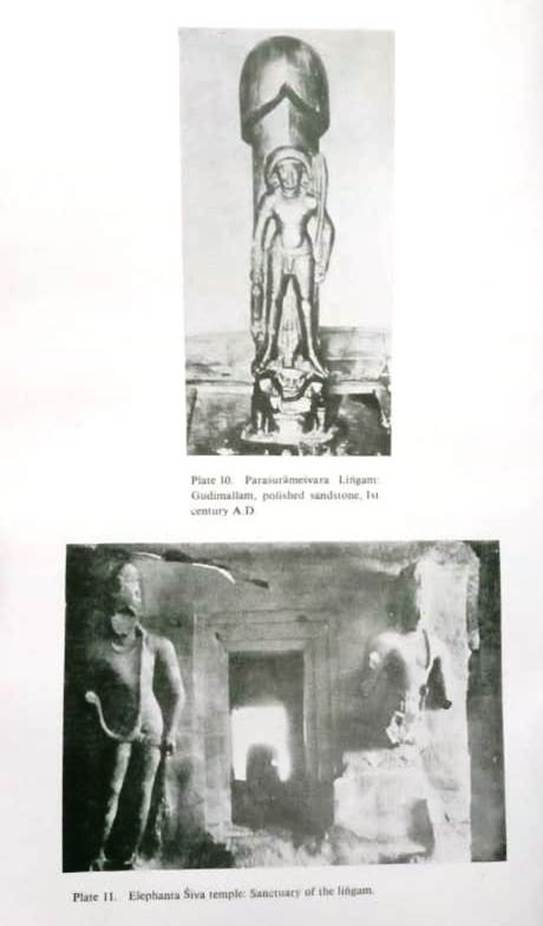

Plate 9B. Egyptian black Net (New York Museum)

Plate 10. Parasurameśvara Lingam: Gudimallam, polished sandstone, 1st century A.D. (From "History of Far Eastern Art" by Sherman E. Lee, p. 98, pl. 107)

Plate 11. Elephanta Śiva temple: Sanctuary of the Lingam (From "The Art of Indian Asia" by Zimmer, Vol. II, pl. 262)

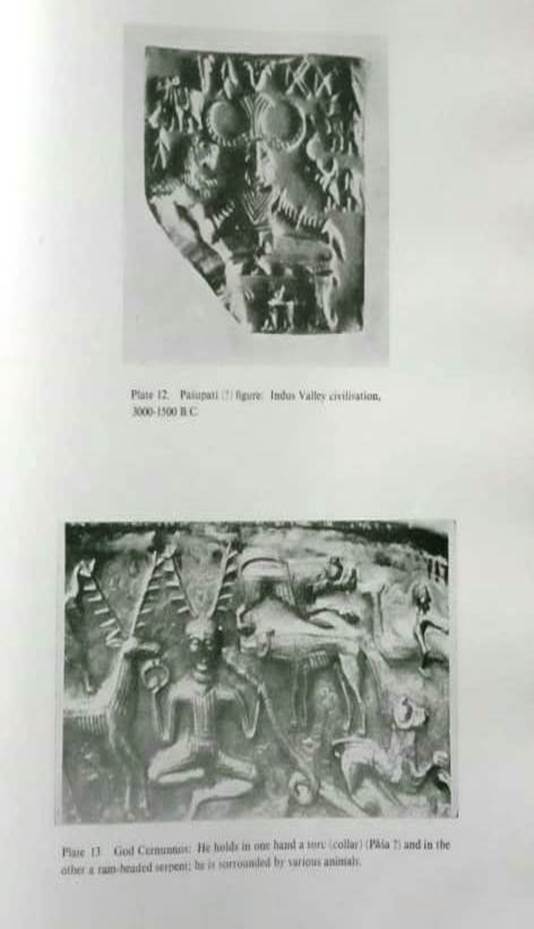

Plate 12. Pasupati (?) figure: Indus Valley civilisation, 3000-1500 B.C. (Ibid., pl. 2a) (Cf. pl. 13)

Plate 13. God Cernunnos: He holds in one hand a torc (collar) (Pasa?) and in the other a ram-headed serpent; he is surroundedby various animals. Silver plaque from the Gundestrup bowl (From "New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology", p. 224) (Cf. pl. 12)

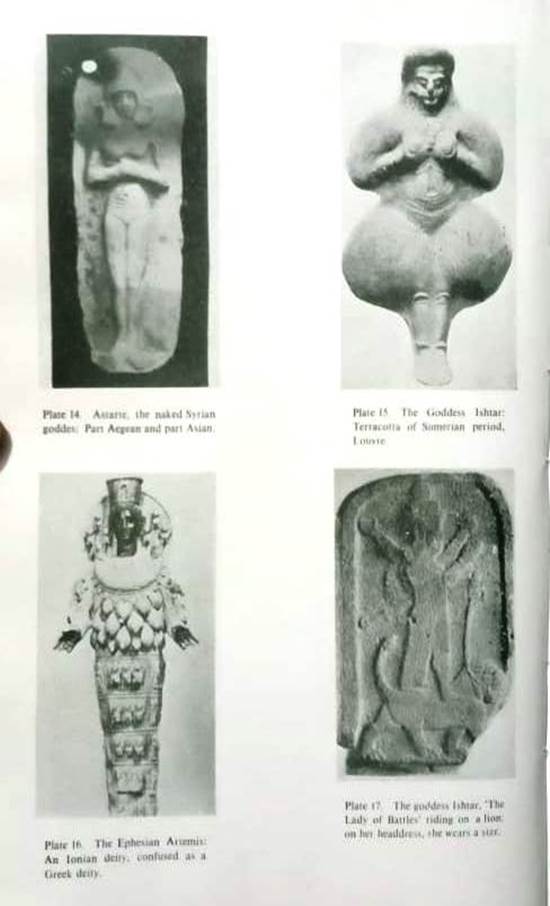

Plate 14. Astarte, the naked Syrian goddess; part Aegean and part Asian (From "Lost Worlds", p. 316) (Cf. pl. 9B)

Plate 15. The Goddess Ishtar: Terracotta of Sumerian period, Louvre (Ibid., p. 57)

Plate 16. The Ephesian Artemis: An Ionian deity, confused as a Greek deity (Ibid., p. 110)

Plate 17. The goddess Ishtar, "The Lady of Battles' riding on a lion: On her headdress, she wears a star (Ibid., p. 63)

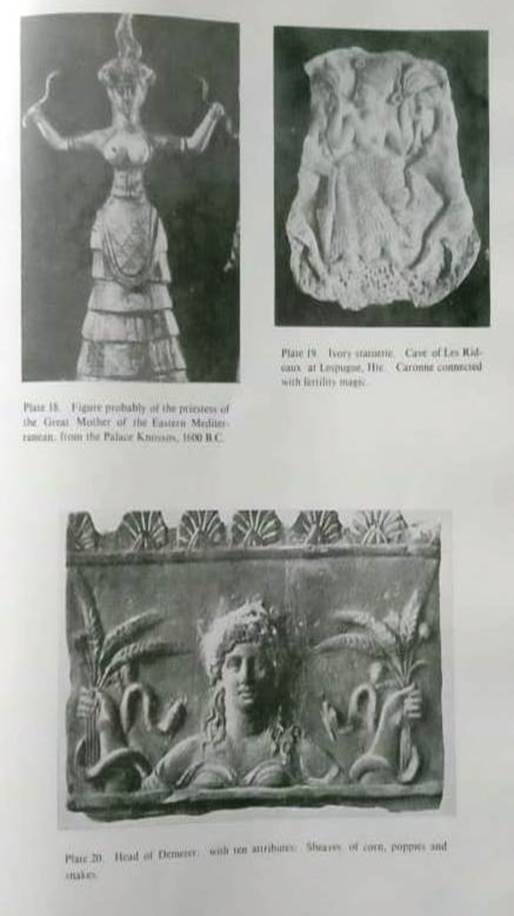

Plate 18. Figure probably of the priestess of the Great Mother of the Eastern Mediterranean, from the Palace Knossos, 1600 B.c. (Heraklion Museum): The serpents which she carries are age-old symbols of fertility (Ibid., p. 197)

Plate 19. Ivory statuette. Cave of Les Rideaux at Lespugue, Hte. Caronne connected with fertility magic (Ibid., p. 8)

Plate 20. Head of Demeter; with ten attributes: Sheaves of corn, poppies and snakes. Terracotta, Terme Museum, Rome (Ibid., P. 148)

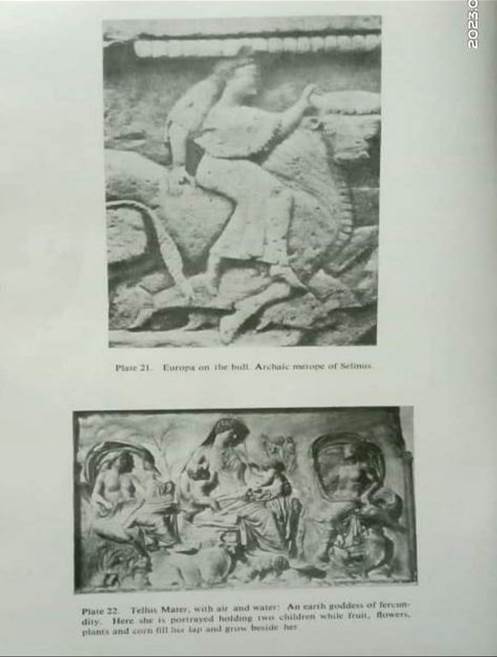

Plate 21. Europa on the bull. Archaic metope of Selinus (From "Themis" by, Miss Harrison, p. 448)

Plate 22. Tellus Mater, with air and water: An earth goddess of fercundity. Here she is portrayed holding two children while fruit, flowers, plants and corn fill her lap and grow beside her (From "New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology", p. 205) (Cf. Hindu Durga Dasabhujá image of Bengal)

Plate 23. Egyptian papyrus: 'Shu' creates the world by separating the sky goddess from the prostrate earthgod

Plate 24. Chinnamasta (Kangra, 18th century A.D.) illustrates the cycle of Life (creation) and Death as one process

Plate 25. Camunda: the Black Mother (Sculpture from Orissa, 11th century A.D.): The fiercest and most bloodthirsty form assumed by the Mother (From "New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology", p. 322)

Plate 26. Amaravati (11th century A.D.): Adoration of a Stúpa by Nāgas (From "The Art of Indian Asia" by Zimmer, Vol. 11, pl. 79)

Plate 27. Marble Stúpa Amaravati (Late Andhra period, late 2ndcentury A.D., Govt. Museum, Madras) (From "History of Far Eastern Art" by Sherman E. Lee, p. 93)

Plate 28. Omphalos: A holy stone found as an evidence of phallic worship (From "Themis" by Miss Harrison, p. 398)

Plate 29. Omphalos: The height is to be noted, for this heralded the Roman custom of erecting such monuments around which public festivals were organised (Ibid.)

Plate 29A. The Code of Hammurabi

Plate 30. Typhon: His body was composed of coiled serpents and his wings blotted out the sun. Cf. legend of Garuda (From "New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology", p. 91)

Plate 31. Khepri, the scarab-god: Before him he rolls the ball of the sun, pushing it into the Other World in the evening and over the horizon in the morning as the scarab beetle pushes before itself a ball of dung. As a symbol of continuity of Life and Creation, Khepri was the most popular symbol of veneration painted on walls, designed on ornaments, decorating crowns etc. (Ibid., p. 15)

Plate 32. Achaemenian fire altars, which still stand in a sanctuary near Cyrus's capital of Pasasdadae (Ibid., p. 310)

Plate 33. The Phoenicians Ishtar represented symbolically in this stele found at Dougga in Tunis, not far from the site of ancient Carthage (Ibid., p. 84)

Plate 34. Acadian Naram-Sin: Sargon's grandson Naram-Sin (Acadian Dynasty) took a title that had belonged to certain god-kings of the four quarters of the world-and was himself deified. A magnificent expression of his divinity in the pink sandstone stele below, on which, wearing the horned helmet of the gods, he stands over two foes as a third falls headlong and others plead for mercy. His men, follow him up the wooded mountain slope; but the king stands alone at the summit, close to the great gods whose stars appear overhead. An example of deification of mortals, victory of one faith over another, and portrayal of legends like Ba'al killing Aleyin. (From "Lost Worlds" by Davidson and Cottrell)

Plate 35. The seal of a bull (Ibid., p. 267)

Plate 36. Mithras sacrificing the bull (Mithraic altar, 2nd century B.C.): A god common to both Indian and Iranian Mythology though under somewhat different forms, Mithras was one of the great Persian gods. The immolation of the bull was regarded as symbolising a cosmic event, viz., sun overcoming the house of Taurusin the Zodiac (From "New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mytho- logy", p. 316)

Plate 37. Ellora Kailasanatha (From "The Art of Indian Asia" by Zimmer, Vol. II, pl. 208)

Plate 38. Hari-Hara: Sandstone 6th century from Prei Krabas (From "New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology", p. 361)

Plate 39. Śiva, King of dancers (From "The Art of Indian Asia" by Zimmer, Vol. II, pl. 2a)

Plate 40. Ellora Šiva Tripurantaka (Ibid., pl. 226)

Plate 41. Ardhanariivara: Sculpture from Ellora Caves, 7th century A.D. The curious composite figure, half man and half woman, represents Siva and his 'Sakti' (From "New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology", p. 371)

Transliteration of Sanskrt Words

|

A |

As |

In |

-non- |

|

A |

As |

In |

-car |

|

I |

As |

In |

-hit |

|

i |

As |

In |

-peel |

|

u |

As |

In |

-pull |

|

u |

As |

In |

-smooth |

|

r |

As |

In |

-rich |

|

e |

As |

In |

-pate, nay |

|

ai |

As |

In |

-kite |

|

o |

As |

In |

-note |

|

au |

As |

In |

-mount |

|

c |

As |

In |

-birch |

|

ch |

As |

In |

-Churchill |

|

t |

As |

In |

-fort |

|

th |

As |

In |

-hit-hard |

|

d |

As |

In |

-bird |

|

dh |

As |

In |

-bird-house |

|

t |

As |

In |

-Turin(as pronounced in Italian |

|

th |

As |

In |

-Stratham; Martha |

|

d |

As |

In |

-this |

|

n |

As |

In |

-burn; horn |

|

v |

as |

In |

-vow |

|

s |

as |

In |

-shin |

|

s |

as |

In |

-shard |

|

s |

as |

In |

-certain |

|

h |

as |

In |

-home |

|

nc |

as |

In |

-lunch |

I

RELIGION, RIGHTLY understood, is a personal adventure to relate individuals to the cosmic; multiplicity to Unity; so that man could come nearer to man, form a peaceful society here, and attain blessedness. To be religious is to recognise the Divine or the Absolute in others, not in the human beings exclusively.

Good is its only aim; happiness (bliss) the only prize. No other aim, either of freedom from pain in this life, or of celestial success in the next, tempts the religious man. To be religious is to attain freedom from temptations-all temptations, even temptations of bliss. Life eternal is a Reality to him; to his resurrection is not merely a vague promise, but a definite possibility. He does not await an entry into the tomb to rise from it again. For him heaven is within himself, and is attainable right here. So his is a perpetual struggle to resurrect himself from within his inward conscience; to resurrect the paradise lost to outward temptation. To reach the depths of his potential individuality from the surface of his apparent and relative individuality is the one great adventure of the man of religion. For him his soul is the seat of his bliss. All religions seek the Soul. The Soul is the Bethlehem where the hope for Resurrection shines as a guiding star. All religions, following this or the other path, have to make a pilgrimage to this Bethlehem. The man of religion seeks his salvation in the redemption of his own soul. By so doing he becomes the universal man, a guide to the deluded. He becomes a Yogin.

In other words, religion, to be worthy of its ideal, must deny a fanaticapproach, which could only result from a failure to appreciate the other man's point of view to emphasise that the only way of attainment of perfect bliss, freedom, is the one known or practised by him. Blinded by igno rance, tutored on crude dogmas, our reason, the one apparatus of under- standing, gets blunted. Religion, as it is, has been deluded to the extent of incongruity, even perversity. When religion is blinded by ignorance, and armoured in dogmas it indeed becomes a formidable weapon in the hands of those who love power for the sake of power. Often in history the success of a religion has been measured in terms of material prosperity and splendour of showmanship; and more recently, by a show of numerical strength of masses branded with a set pattern. As a result, religiosity has suffered; and conventions and rites alone have goaded the bewildered into the trap-gate of fear and greed. To conquer fear has been the ideal of the Seeker. Religion admits of no fear. Love and fear cannot live together.

What is Love without feeling? What is philosophy without thinking? It is in religion that love and philosophy, feeling and thinking attain a happy, human union. The popularity of religion lies in hope. As long as man would be in need of hope, society would be in need of religion, in spite of the cynics, the sophists and the materialists.

As there are stages in human life, when religiosity is ignored due to intellectual cynicism, or giddying materialism, there is also a state when the blessing of a sense of proper values, of moral dimensions, dawn on the erstwhile errant. Then alone one could be said to have attained real manhood. A large majority of the matured devout of today have been the chauvinistic materialists of yesterday. To be religious is not to ignore life or matter necessarily. On the contrary, proper religiosity develops only with the correct evaluation and utilisation of life and all that succours it. All religions enjoin on the devout the duty of selfless involvement with life.

Even before man thought, man loved; even before man loved, man lived. Living, man knew, was mating; and mating, man knew, was living. Somewhere, the man who spends in mating also stores by it. Somewhere, spending and storing, Life and Death, is one process in different manifestations. Life has been the strongest enigma to man. The search for the key that could solve the riddle of life has seen many a Sphinx disappear in dust and yet the problem of life remains a problem unsolved. Religion has been one of the most fascinating and significant landmarks in civilisation's journey towards the achievement of the Spirit of Man. It has brought hope to the hopeless, light to the blind, courage to the down-trodden and discipline to the savage. In spite of the abysmal exploitation of man and materials perpetrated from ages immemorial by the guardians of the different churches in the name of religion andgod, religion still holds the faith of Man. No single idea so easily captivates the thoughts and imagination of mankind; no other single idea would so spontaneously gather the largest number of men, women and children under one banner as the idea of the church, of something beyond the common human which as a Power consoles, assimilates, pacifies, makes man bear pain and sufferings, betrayals and bereavement with some amount of compensating consolation. Life attracts and repays by its own charisma. There is a Power succouring this Life Force.