Saivism

And

The Phallic World

B. Bhattacharya

Volume II

Munshiram Manoharlal

Publishers Pvt Ltd

Contents

A. Orthodox Southern Siddhanta.

III. Nada Tattva or the Sound-System

IV. Pasa and the Hindu Concept of Sin

II. Kashmir-Saivism is Realistic –Idealism

IV. Realised Prophets, and Reality

I. Mind And The Phenomenal World

IVA. The Churning of the Ocean

IVB. The Descent of the Ganges

VI. Vishnu Siva Rivalry and Lingam Legends

IX. Tantra-Empiricism and occult Legends

X. Popularity of Siva and the Outcastes

XIII. Sundry Other Myths and Chronicles

8. HINDU ICONOGRAPHY AND SIVA FORMS

I. Hindu Iconography and Western Misconceptions

Chapter Six

A. Orthodox Southern Siddhanta

I

“The Saiva Philosophy,” says Dr. S. N. Shastri, “is typical of the entire range of Hindu thought.” This appears to be true. Like all other systems of Hindu thought the Saiva system too had to pass through the close scholarly enquiries which are no characteristic of the subtle Hindu mind. Śaivism as a system of spiritual metaphysics, through the centuries, pendulated between Idealistic Monism and Realistic Pluralism.

Whilst this could be so for Hindu thought in general, and of Saivism in particular, it need not, however, cause any surprise. Any system flourish- ing over centuries at a stretch without any break, and which had to absorb, like a flowing river, a number of tributary opinions which typify different ages and people, is expected to contain signs of different grains of thinking.

The basic teachings of Saivism, like those of the Upanisads, enjoy, in this way, a freedom from dogma; these are distinguished by a rich variety of forms. Various explanations have been offered from time to time for justifying Saivic stoicism on the one hand, and elaborating its mystic recensions on the other. Naturally, therefore a number of schools, all sheltered under the umbrella of Saivism, has left a library of spiritual literature and religious forms, all inspired with the fulfilment of transcendental realisation. Most of these seek the abstract; some of these attempt to reduce the abstract to mythological objectivity; andvery few indeed, persist in their phallic forms reminding of their primitive fertility motifs.

The pure monists believe in an idealised Siva-concept. These are the Kashmir Siddhantins, who hold on to monism with a Vedantic conformity. These are the propounders of Sphota, Spanda, Pratyabhijñā and Trika. All these schools belong to a heritage of metaphysical rationalisation, leading to knowledge and realisation. This is not to say that all Śaivas are pure monists. The Southern Siddhantins and the Lingayats are not. The other extreme of realistic pluralism is held by obscurantist sects like the Pasupatas, the Mahāvratas, the Kapālas, the Bhairavas, the Vāmās, etc. By and large in the sophisticated Hindu Hierarchy of systems, these latter are considered as mystically remote, and formally obscure, and at most times ethically abhorrent. The phallic primitivity in Siva worship has never been seriously considered in Hindu metaphysics.

These extremes of popular religious practices range from paleolithic adoration of crude nature in tooth and claw, to abstract meditation and aesthetic dedication. Extremes of religious faith characterise extremes of metaphysical arguments. The presence of such extreme opinions with- in the Saiva schools of thought go to show (1) how ancient Śaivism is; (2) how widely popular is its universal influence; (3) how many trends of opinions have found accommodation in Saivism; and lastly (4) how liberal is the term Śaivism as different from the codified rigidity of Brāhmaṇical Vedism. Śaivism ranges from strict conservatism to liberal, even communistic proletarianism. Šiva happens to be the most popular 'god' of the Hindu faith; he also enjoys the distinction of being adored by all, irrespective of castes. He is adored by the Danavas, Yakṣas, Rākṣasas, Kinnaras, Ganas, Guhyas, Siddhas, who are not the Devas, or the elect.

The monistic form of Saivism leads towards individual rigours, most of which prove to be very trying. All of these are strictly ascetic. Śaivism being closely attached to Yogism has to be ascetic. Śiva has been termed as the Prince of the Yogis, Yogiraja, or Yogesvara. But it is not so with the dualistic Saivism. Dualistic Saivism leads to the Tantric practices, where the acceptance of Mother-image permits bi- sexual participation, and encourages to live the life of a householder. This would not be permitted to a monastic and a monist, who must conform to the rigours of asceticism.

There is still another form, the realistic pluralism which is diversified by a number of sectarian ritualism to be discussed later. It is permissive and congregational. Its mystic obscurantism, and its crude eroticism have always drawn scorn from a section of spiritualists. Quite a large section of this class like the celebrated Freemasons, thrives under a cover of underworld mysticism. But to call this mysticism would behighly erroneous. Of all forms of worship current in the Hindu fold, this one particularly appears to bear a distinct stamp of alien origin. It appears to be so because it appears to be dependent on the riff-raffs of spiritual dilettantes, who have little need either for a metaphysical base, or a philosophical content. At its best the form could only relate it to some primitive forms.

A study of history, as of philosophy, has been regarded by scholars, specially of the last two centuries, as antagonistic to religious beliefs. But modern history-writing itself has grown into a philosophical exercise of its own kind. Acceptable justifications for religions demand for Ex- their sustenance some philosophical base, and historical support. treme empirical claims have been found to mislead the mind. Unrestrict- ed emphasis on empiricism leads to scepticism; and a sceptic mind falls an easy prey to a cynical vacuum of spirit. Faithlessness is not always a particularly helpful guide for man to live in peace with himself.

Religion and Philosophy

In spite of it all, most modern minds find it very hard to accept a religion to respond to their inner quest for peace, specially when they associate religion with mere dogmas and forms unrelated to any sub- stantial content. The modern mind has lost its faith in faith as a performer of miracles. Those who still advocate the gifts of faith have been stigmatised as weak minded individuals, victims of regimentation and euphoria. Reason and analysis must fill in the emptiness created by the interrogative man, who is so well packed with a variety of cheap informa- tion, for good or bad, from all over the world.

In a developing culture, and in our present state of sophistication, philosophical thinking becomes more than ever an integral part of the true life of religion, and a condition of its effective renewal and perpetuation in a form we can wholeheartedly acknowledge and find adequate to the needs of our times at all levels.1

Of course, we fully appreciate and endorse this view of Dr. Lewis in a world where demands of self-expression, socialism and democracy have successfully removed authoritarian autocracy and monarchical despotism. That the authoritarian and dogmatic stand of churches and church-heads would be successfully challenged, or even denounced, is quite understandable. The progress of reason in defiance of dogma is correlative to the progress of the people in defiance of autocratic authority. Religion, in order to fully satisfy the human craving for spiritual peace, must be substantiated by a rational and philosophical content. Religion too calls for its dialectics. Hindu thought fully supplies it, and in profusion.

Hence the Six Systems; the Upanisads; hence the correlation between Hindu Grammar, Hindu logic and Hindu philosophy. Even the grammar of Hindu Music, Dances, Sculpture, Architecture, nay, even the Hindu alphabets (very difficult to believe it) are correlated to metaphysical con- tents leading to the quest of the inner spirit. Nothing is left to guess, hypothesis or dogma. Herein lies the secret of the success of this most ancient way of life, known as the Hindu life.

Theologians, for their own reason, and communists for theirs, are expected to contradict the above view. In the eye of one, religion without philosophy is as reliable, as in eye of the other, both religion and philosophy, are obstructionist and redundant to the ultimate social fulfilment of the common man. Both these views lack the objectivity of the dispassionate; and are open to prejudices that single-track minds often find themselves led to.

Life without wonder and without the joy in wonderment, could become boring as an existence without meaning and purpose. Mere vegetation- existence is continuity without meaningfulness. Any attempt to discover this meaningfulness in life calls for a dedicated emotive subjectivity. To consider matter alone, or materialistic causation alone, out of the context of Reality, is an absurdity. Life has a purpose. To discover it is Dharma; to act on it is Karma; to benefit by it is Kama; and to be finally liberated from it through fulfilment is Mokṣa.

Thus the need to feel, to participate and to react becomes imperative for the growth of an individual who could relate existence to meaningfulness and purpose. The appreciation of the full state of manhood of an individual in a clan or community adds confidence to life. This inherent subjectivism of living distinguishes man with the stamp of individuality. The biological human entity is not the psychological man; and the psychological man is not the metaphysical thinker. Man is biologically a machine; metaphysically a thinker; and psychologically an individual. His identity demands a recognition of all the three. He could be happy only spiritually. Modern studies of mind and feelings, of matter and nature of matter, have been gradually breaking down the barriers that had kept religion and philosophy so long apart. To think is to take recourse to philosophy. Science has progressed along the path of analysis; but philosophy releases the charm that synthesis provides. Philosophical thinking has been disciplining gradually the unchartered boundaries of man's mind-boundaries which are laid down by well intended beliefs- religious, social or political. All our views regarding material existence are being highly influenced by how we think about the material world we live in, which alone could help us to know the very nature of existence. If we want to be happy, we have got to be aware of our inner personality where we are essentially alone and spiritually accompanied.

The ethical man needs moral thinking, that is, a training in correct appropriation and allocation of values. The full enjoyment of our happiness is inextricably involved with our sense of good and bad, right and wrong. In what we call our practical life, we may succeed in by- passing philosophical scruples at certain times; but in arriving at practical decisions, we could be nobly and profitably assisted by a scrupulous evaluation of choice, and discriminating logic of consequence. Our failure to do this could lead to lamentable tragedies. To attend to such fore- thoughts is to develop patience for the mind, and toleration for behaviour. Insistence on achieving these, develops our personality on the one hand, and engenders on the other in us the very rewarding virtue of collective responsibility.

Sense of responsibility affects sense of duties; and sense of duty may undergo variations according to varied situations. When we are called upon to decide on declaring a war on cholera, we do not put exactly the same set of logic to test, as when we are called upon to decide on declaring a war on another country or people.

Philosophy, then, can make a considerable difference in some ways to the activities or other subject matter which the philosopher investigates and I believe that sound philosophical thinking can- not only prevent us from falling into misleading errors, or provide us with illuminating distinctions, but in other ways extend our sensitivity, and deepen our experience in such matters as aesthetics, ethics, or the pursuit of science. The notion that philosophy influences nothing beyond itself is the product of a very negative and narrowly formal conception of the task of philosophy current today.2

In no other field the truth and the wisdom of the above view (of a noted philosopher and scholar of comparative religion) proves so true as in religion. The view that religion and philosophy are opposed to each other is, thanks to a subtle, refined and thorough study of the East by the West, and vice versa, being entirely replaced by the realisation that all great religions are fundamentally based on philosophy. Religions, which have been surviving on authorities of voiced truth, fall victim to dogmas which are being found more and more untenable. Such religions are realising the need for a re-visioning of their earlier stands. Practising dogmatic religions based on words of prophets are gradually readjusting their positions, so that these could answer the insistent demands of the over-growing national claims of a highly informed generation. A slant of emphasis from rituals to ethics, from sectarianism to ecumenism, from prejudice and authoritarianism to logic and understanding is now being happily noticed all around. Religion is being re-claimed through the application of philosophy to a scientific reassessment of history, which includes anthropology.

Compared to these, those religions which draw from truths realised, and statements made by a number of masters of the spiritual world, and others based on a consideration of man's eternal query about the logic and nature of things, are being revalued and rejudged as sources for rational approaches to the nature of god and creation. Today, more than ever, theological scholars need the assistance of philosophical thinkers. Religious contents have to be rationalised for easier acceptance and assimilation. Growth of democracy is not very conducive to citations of authorities in matters of conscience, ethics and morals.

Dogma and democracy are the opposing poles of the human mind. Any faith founded on an individual mind which has subjected itself to a personal acceptance, has to await the matured blossoming of an under- standing. To a large extent it has to await and appropriate historical situation. Faith, flourishing against a conducive force, and background of history alone, is expected to produce the desired results. This is as true of the religion of spiritual progress, as of the religion of Marxian dialectics. The faithfuls of the society have to choose their time for taking pains in training the society through individuals trained and tested for their spiritual contents. Religions, to be effective and fruitful must draw faith from understanding. This observation could be true of a spiritual, social or political religion. It is Dharma for the convinced; not for the zealot. Even the so-called mystic religions have to turn back at some stage, and face obstinate quests from individuals regarding the prognosis and the rationale of their rites, practices, dogmas and motives. This fundamental principle was inlaid in the Hindu mind. By attaching religion with philosophy it liberated all dogmas through the sabrecuts of reason. In Hinduism religion and philosophy meet inextricably. Hinduism, strictly speaking, is more a well thought out practical way to attaining peace, than a 'religion'. This accounts for its perpetuity. This accounts for its faith in coexistence. This also accounts for its insistence as being called a Dharma. Mokṣa or liberation from doubts, from worries, from depression, from complexes, in Hinduism is more important than Heaven. This, socially and individually speaking is the chief difference between Hinduism and Vedism.

This has nowhere been as rigidly laid down as in the ancient treatises of the Hindus. The Vedas provide the pasture from which the body of the Upanisads draw their sustenance, and collect the milk of thought; and the Gita draws all the milk to feed the common man with spiritual awareness. In the history of human analysis of the transcendental, the place of the Upanisads ranges very high indeed. Herein for the first time, attempts have been made to present a synthetic rationale about a central conscious subjectivity. For the first time reference was made to the cosmic conscious field. This central conscious cosmic field was presented as asubject-object mystic complex. The full realisation of this knowledge, realised, through meditation alone, could lead to the Supreme Entity, from which proceed thought, thinker and thinking.

Thus, from the very remotest of times spiritual guidance of an utmost technical nature had been laid down for the benefit of posterity. The cult of realism which led the Western mind for over a century to acquiesce to the acceptance of cold materialism has only lately received some shock through modern military threats. The apparent urgency for peace is really inspired by the fear of a total annihilation as an alternative. Such an approach lacks the spirit of ethical alertness. A reassessment of the cult is gradually turning the disillusioned and the frustrated to look for saner counsel in the idealism of Hindu and Buddhist thoughts. Even the age-old Greek heritage of Thales, Plato, Parmenides, Pythagoras is being reassessed in this light; and the antiquity of Hindu idealism is being gradually recognised. Scholars are getting keen and earnest in re-discovering some possible means of communication between the minds. The discovery ancient Upanisads, and the contemporary of the Essene scrolls has added urge to such scholarly approach. Mere dogmatic assertions in favour of a 'chosen people' or 'chosen faith' is no longer viewed by the scientific and interrogative man as the finality of judgment. In order to 'be' the best, it is no longer enough to die and claim to be the best; but it is required to live in essence of reason and understanding, and by living to 'prove' to be the best.

Philosophy, to be effective through practice has to work through forms. Exciting forms, for appeasing the mystery of the supernatural, took the shape of superstition and mystic cults. But these cults had forms of their own; and the forms had run so deep into the social traditions that it has become very hard to be got rid of them. Force was tried, only to fail. Forced suppression of forms drive superstitious practices to the underworld of mystic magic and sorcery. Clandestine practices are no Cults and their forms sublimate answer for healthy spiritual pursuits. into religious forms when these get wedded to the vitality of philosophy, and metaphysics.

Just through a great piece of luck the Hindus were to be associated with the traditions of the Vedas and the Upanisads which emphasised so much on psychology, art of relaxation, transcendental meditation and the fundamental mechanism of the relation of individual personalities with the Cosmic. This lucky tradition permitted the Vedic people, later, to accommodate many of the religious trends with a variety of gods without much ado. Restrictive opposition to beliefs leave contrary effects to social mind. A spirit of defiance to authority counteract the basic spirit of universal peace. This Aryan process of accommodative acceptance of the popular along with the knowledge of the Cosmic, made itpossible for the Vedic mind to merge philosophy and religion into one.

One of the forms of such interpretative acceptance of the ancient and traditional into the sophisticated Vedic culture was what is known to be Śaivism, the worship of Śiva, not only in the Linga form, but also in anthropological and Zoomorphic forms. Legends gained honoured places in myths; and the Siva tradition developed into a unique philosophy all its own.

The Three Branches of Saivism

This shall be studied now. Śaivism as a philosophy has been cultivated earnestly in Kashmir. It has its own interpretation and analyses, mainly Vedantic. Its emphasis on metaphysics has given it an esoteric obscurity which, when understood properly, reveals the intellectual subtlety and spiritual sublimation underlying most Hindu theological forms, but particularly the much maligned Śiva-worship.

The next study refers to the ancient Agama Literature of the Tamils. The emotional content of this form of Southern Saivism is overwhelming in piety and ecstasy. That does not mean that it has no roots in philosophical profundity. It follows a materialistic analysis of the concept of Siva, and leans principally on the Samkhya and the Yoga systems.

Apart from these two, there is a highly challenging revolutionary and reformative school of Saivism, known as the Jangama, or the Lingayata Sect, which, like the Siddhantins, accepts a materialistic approach to the analysis of the Sublime Cause of all events. This materialistic approach together with its spiritual content cuts through a rigidly guarded Vedic caste system, which had degenerated into the practice of denial of privileges to a vast section of the people, inclusive of women in general. Verses in the Manu Samhita on the status of women apropos of spiritual companionship provide ample testimony in justification of the revolutionary stand of the Jangamas. Prince Vasava was its leader. Such degradation of social and religious position of women was the general feature of the expanding patriarchal domination over such areas of culture where previously matriarchal leadership prevailed. Vasava's system of the Jangama Saivism laid the axe at the root of such encroachments of Brahmanical authority over privileges and disabilities. But all these three systems were, more or less, expressions of their times. Forces of history had been operative in bringing them to the fore.

Besides these three, there is also a variety of Tantric and tribal forms practised under the colourful umbrella of Saivism. The phallic overtones, naturally found in these forms cannot be denied. But these have remained all along, like witch-craft or Druid-forms, the pursuit of an underground clandestine section of tribes and downright social degenerates.

A Reassessment of the Hindu Approach to Religion

In a remarkably frank passage Dr. Lewis acknowledges the possible gain that Western scholars could derive from a study of Eastern thoughts. "But however the relation of the finite self to Eternal Self is conceived, and whatever variations of emphasis we may find in the account given of the relation of the one to the other, and of degrees of reality accorded to finite things, the transcendent character of the absolute reality is always very clearly understood in a way that not only lends special interest to these early anticipations of later attempts to conceive the relation of the finite to the infinite, but which also proves exceptionally instructive to those who wish to consider the problem of transcendence as it presents today."3

The italics are mine. I want attention to be drawn to the two facts: one, the phrase 'early anticipation of later attempts'; and two, the phrase 'the problem of transcendence as it presents today'. I want attention to be drawn to the fact that in discovering the Ideal state of transcendence of experience, in discovering the metaphysical correlates of experience, cognition, perception and expression of the nature of Ultimate Reality, modern mind, with its empirical diversion and materialistic limitations, has not been able to surpass either the skill, or the conclusions of what these ancients in the East had been studiously, religiously and conscientiously arriving at with a dour and persistent application of self-analysis. To hold the 'self' in the 'I' as an object of analysis, and sublimate it to a subjective state, has been the greatest achievement of this process.

This approach to the discovery of Truth is known today as the famous 'Hindu approach'. Not too long ago it used to be a scholastic fashion to call it 'speculative, obscurantist and abstractionist'. Much circumvention and guile, a mountain of deliberate bluff and hoax were brought up by the application of 'studied' opinions to support such a view applied with political designs. As a justification of imperialistic expansionism, commercial exploitation, along with the egoistic self-approbation contained in the phrase 'whiteman's-burden', such propagandist misrepresentations proved profitable. The over-enthusiastic evangelists only added more fuel to this fire by dumping all other religious forms as contrary to the True Religion. A new spirit of rededication amongst the Western scholars, specially amongst the regenerated post-war Universities, has succeeded in reallocating the ancient works of the forgotten authors, and reassessing their values. This reassessment has strikingly propagated an intellectual renaissance in the area of metaphysical and spiritual thought which has succeeded, in fact and form, in inaugurating a spirit of real ecumenism amongst the leading world religions, in spite of the embarrassment such scholarly honesty has been causing to some of the protagonists of evangelical and institutional religions, which thrive within anorganisational system of imperialistic bureaucracy. Because of the permissive wave of such democratically inspired sanctions a reassessment of sorcery and magic too is being made as religious studies.

Condemnation of the Siva-worship as a phallic trait and form is just one of those half-truths which are deliberately designed for misleading in the interest of a conversion. In fact such deliberate propaganda has been assisting a fast growth of empiricism, cynicism, hedonism, imperial- ism and commercial expansionism. By causing embarrassment to the gullible, it injects degeneration of faith. It is like brushing sugar to beet roots so that ants destroy everything. Such sententious generalisations, with conceited overtones of condemnation and spite, do not display ignorance alone, they also display something more injurious to the faculty of human understanding and judgement. It displays prejudice of opinion, scantiness of education, perpetuation of vanity, false pride in assumed superiority, misdirected zeal for self-love, and above all, a lamentable exposure of spiritual emptiness. This calamitous attitude could interest, or even profit, a few; but in the ultimate reckoning this deplorable lack of catholicity has shocked the post-war youths, who have discovered that one of the most important motives of Western patterns of religious propaganda has been to accumulate material gain to the establishment, even at the cost of truth and fair play. In this way the established religions have come to suffer much more through their own weapons, which have misfired.

Fortunately, such dogmatic misunderstanding of the Universal Man and his spiritual aspirations, is now being effectively counteracted by scholars of comparative religion, whose objectivity of approach, and subjectivity of scholarship, is gradually succeeding to bring home to the deluded the fact that the spirit of the West has much to learn from the wisdom of the East, which has much to offer to the art of good living, and science of happiness, as laid down positively in their works, which have yet to be studied with an honesty of purpose. The study of comparative religion has been ably assisted by the progress of linguistics, the propagation of tests through translations, the discoveries of archaeology and the disabusement of the imperialistic possessiveness and political gangsterism.

With the spread of democracy and socialism, with the rise of the Common Man, the theory of the 'chosen nation' and the fraudulent idea of the 'whiteman's burden' is being fast exposed. Man is getting busy now to reach the real religion of the soul, a religion for the society, a religion for the peace of man through a perennial philosophy. Such a religion has to rise above the man-made churches, well-stocked establishments, joints of internationally organised systems of brainwashings in the interest of an accumulative society, which are privileged to hold on the capitals of different nations, and above the dogmatic stand on mere revelationswhich stem from some Semetic antiquity. All of this has got to face today the intellectual enquiry of both empiricism and materialism. The religion of the dictator is giving way to the religion of experience, the religion of personal content. A personal god has been forced to get interpreted and represented in the light of personal experience. If this be called mysticism, it is decidedly going to be the future religion of the universal man.

Saivism and the 36 Tattvas

Towards this end, a study of Saivism has much to contribute, because in Savism whatever form emerges as concrete, or iconic, or symbolic, has been reasoned as a projection of an inherent subjectivity into an objective expression. A study of Saivism is basically a study of the nature of Reality.

It is, in a sense, typical of the Hindu idea that religion, divinity, ritual and philosophy, nay, even life and after-life, must of need be linked in a single symphony. For the Hindu, philosophy and religion as well as religion and life are inseparable. The chain of ideas known together as 'Life' at the one end, and 'God the Unknown' at the other end, makes up man's world of form and spirit. The 'Bond', between the two, namely, the known and unknown world, is provided by 'Soul'. The Soul provides the force that links the world of matter with the world of spirit, otherwise known as Siva and Sakti respectively.

These three then, are the primary Constituents (Padarthas): God (Śiva), Bonds (Pasa) and the Soul (Atman).

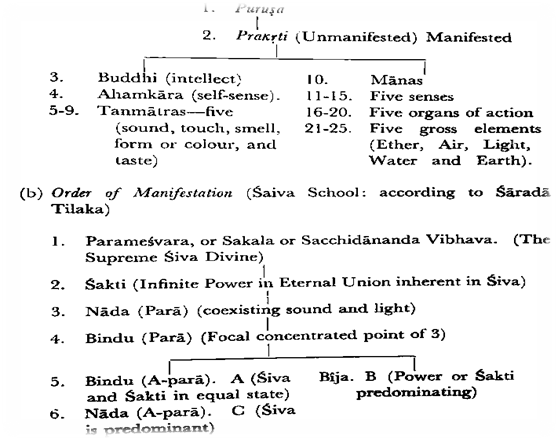

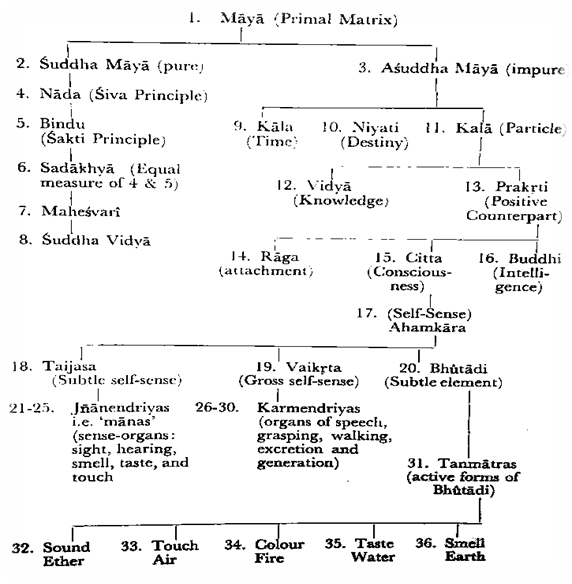

These are to be studied in the light of the 36 principles, 4 (1) known as Tattvas (Tat=That and Tva-ism. Tat-tva-the 'Ism' of 'That', or more simply 'the final principle that makes That, That') Tattvas are active. They are principles that justify further emanations as evolutes from them, of which they become the causes.

The Tattvas remain firm, but Saiva metaphysics itself, as whole, has its variations. These range from idealistic monism, to pluralistic realism. The variance differs in accordance with the independence attributed to 'Soul' or 'Matter'.

In essence the exercise of determining the degree of interdependence of Soul and Matter is not speculative. Such an exercise has a purpose. is to get to know 'What is life for?' This knowledge leads This purpose to a freedom from the chain of 'cause and effect' 'sequence and consequence'. Without their freedom there is no peace. It is a freedom from inhibition, tradition, reciprocation. Without peace, there is no happiness. Without attaining peace and happiness it is futile to try to serve others, and contribute to their peace and happiness. A perfectknowledge of the self alone leads to the perfection of peace and of peaceful service to the self, as well as to others. This knowledge has to be experienced. Such experience is the fruit of meditation. Hence the quest of the nature of the soul that connects God with the World is vital for the Hindu thought: vital, positive and challenging.

Whereas the mechanics of meditation are supplied by the Yoga- system (discussed before), Śiva-Tattva alone leads to the perfect knowledge of the nature of Soul and Matter, and of the relation between the two.

Variations of the Śiva-Theme

The Saivic orthodox forms deal with the variations of this philosophy. The orthodox form of Saivism does not include the Pasupatas, Maha- vratas, Kāpālikas and Bhairavas, who are regarded by many as hateful and obnoxious. These are the Vama-Märgis-the followers of the 'contrary' way: contrary to the accepted orthodox way, which relate to the Systems. The Vāmas are really not as useless or as misguided. Truth of Reality might not be theirs, but they are very near to the proper destination. Like the Upanisads themselves, like the differences in Jainism, Buddhism, Christianity or Islam, some polemical differences in Saivism were inevitable. Schism is the inevitable after-growth and by-product of metaphysically oriented points of view, specially when such points of view, due to the external preconditions, of history, geography and culture, are inevitably influenced by local faith, prejudices and traditions. When such points of view are exposed to alienated areas of comprehension, when these had had to pass through long run of commonly held contrary opinions through ups and downs of historical shocks, several diversifications of a parent idea become almost inevitable over the centuries. Time alone has a dissolving influence. Such schismic diversifications of a central parent idea, therefore, have characterised even some of our comparatively modern religions. It is no wonder that Śaivism, which has been indirectly related to the most primitive of faiths, and which claims to be related to as ancient a tradition as the Vedas, if not to even earlier times, must have had several forms. Kashmir Saivism, known as Pratyabhijñā (Theory of Pratyabhijña Experience), had Abhasavada (Luminism) and Spanda (Thrill), as its two cardinal lobes. The Trika (as, the three together is known) developed into a synthetic philosophy, on which the thought-currents of the ancient Aryan and pre-Islamic Atharvan traditions of Persia, Parthia and Bactria made deep influence. In its monistic emphasis it was a challenge to Samkhya, and favoured the Vedic. This was, of course, due to a cultural and geographical contiguity. The same syncretic reason accounts for the mysticism present in Kashmir-Saivism, which is felt through its metaphysical abstractions onthe one hand, and its physical and emotional symbolism on the other. This abstractionist symbolism, however, was not so emphatic in Southern Saivism known as Saiva Siddhanta and Vira-Saivism. Both of these, as off-shoots of the Agamas, believed in the dualistic emotional ecstasy of Bhakti. Both of these developed in the Southernmost part of India. As the earliest source available in Saivism we shall deal with the Agamas first.

Agamas: Sources and Propagation

Discussing about the sources of knowledge Rāmānuja considers that Aitihya or Traditions are dependable sources of knowledge, specially when the sages (of later times) vouch for their credibility from their respective experience. These are the Agamas; and when these are not supported by direct experience, and when these are mere products of feeling or inference, then they are known Agamābhāsa.

Agamas (although said to have been records of dialogues between Śiva and Śakti), are also reputed to have been put to practice by the great Vasudeva himself. As such the Vaisnava Agamas enjoy a prece- dence over the Saiva Agamas, which came later. But both support two points: both support Dualism in adoration; and both support admira- tion or Bhakti, and all that is associated with its practice, to be absolutely necessary for achieving the Parama-pada, or the highest state.

The Pallava king Rajasimhavarman leaves an inscriptional record in the Kailāśanatha temple of Canjeevaram, and mentions 28 Agamas, all of which refer to Siva (5th cent. A.D.). Of these Kamika Agama is the most important. Tirumurai, a compilation of Saiva hymns by Tirumurai (1000 A.D.) is included amongst the Saiva literature. Thus between 500 and 1000 A.D. the Siva Agamas have been persistently referred to by the Acaryas. The Agamas have indeed been quite ancient. Śaiva Siddhanta depends on both the sources of the Vedas and the Agamas. Nilakantha, a fourteenth century commentator on Brahma Sutra, undertook the task of reconciling both the Agama tradition and the Veda traditions in establishing the contents of the Siddhanta. Saiva saints and poets known as the Acaryas like Manikkavasagar, Sundarar, Nambi Andar, Nambi Sambandar and Appar together constitute the core of the exposi- tionists of the Agama traditions.

Some of the hymns of the Agama tradition have been collected in the appendix (q.v.). Even in translation the spiritual content of the emotional compositions are unmistakable.

But the earliest Upanisad which is considered to be the first document of the Vedic tradition in Saivism is the great Svetasvatara Upanisad. Without dealing with its contents at this place we propose to add in the appendix a comprehensive translation of Svetasvatara. To understandappropriately the spirit of Saivism a reading of this Upanisad is indis- pensable.

Two Types Saiva Agamas

The dualistic teachings of the emotive Agama literature was popular in the Tamil-lands; but Samkara preached his Advaita; and the Advaita Saivism found popularity in Kashmir, where it substituted the Agamic dualism. But in the South the fervent appeal of the Saiva hymnal treatises, the Tevaram and the Periya Puranam held the devotees' heart and soul. Soon it was able to attract the support of the Pallava Kings and the Chola Kings, through whose mighty empire Saivism spread beyond the seas to Indo-China and Malaya and Eastern archipelago. Since the sixth century Saivism enjoyed a rare patronage which completely eliminated the influences of the godless Buddhists. Saiva Siddhanta was a much later development (13th and 14th cents.). In 1160 Vasava, the Brahmin Minister of the Chola King Bijjala, took up the traditions of an obscure form of Saivic rites popular amongst some of the tribes, and gave it an intellectual basis for expounding a very reformative and revolutionary form of Saivism known as Vira Saivism. This form of Saivism was responsible for driving away the influences of Jainism and Buddhism from the deep South and the Kannada districts. Because of the Athan- asian variety of strict moral code followed by Vasava many relate his movement to the Egyptian influence. But of that, later on.

Besides the Agamas there are several Upapurānas which have contri- buted to the Siva-literature. Sivapurana, Saurapurana, Sivadharma, Sivadharmottara, Sivarahasya, Ekamrapurana, Parasara-Upapurana, Vasistha- Lainga-Upapurana, Vikhyada-Purana, etc., etc., are the later Upapurānas on which the history of Saivism has to rely. But the most important docu- ment in this category is the Vayu Purāna. Besides being one of the most early Puranas, the Vayu has the distinction of being the least inter- polated of the Purāņas. On this Purana Saivas have to depend the most (besides the Svetasvatara Upanisad) for their references in the strictly Brāhmaṇical canonisation of the Vedic Rudra into the popular Śiva, who as the co-partner of Sakti contained the ancient and the modern, the past and the present, the Vedic and the tribal, the Yogic and the ritualistic into one system, the Saiva system.

Other Sources

Who were the original compilers of the Purana form? Some say the Ksatriyas, and others say, the Brahmanas. The Kṣatriya supporters mention that Lomaharṣaṇa, a Sûta, and so a Kṣatriya, has been thenarrator of most of the Purānas. But was Lomaharṣaṇa a composer, or merely the transmitter? Bṛhaddevata mentions the custom of reciting Mantras, and the history of the Mantras formed an imperative part of the Brahmanical Yajñas; and the reciters were invariably the Brahma- nas. There is little doubt about the fact that many of the Purāņas contained in the Brahmana such texts as were inherited by the Vedic This view is amply supported by the priests from the ancient ancestors. Brahmana texts, which abound with incidents and anecdotes which provided the germs for the future growth of the Purāņas. But there is little doubt that the Suta, as a royal chronicler, and enjoying a position in the court only next to a ruling monarch's brother, as a friend and accompanying hero, was the accepted authority for any type of historical reference, ancient or current. Satapatha Brāhmaṇa, Yajur Veda and Pañcavimśata Brāhmaṇa support this view. This is the reason why Atharva Veda, and Bṛhadaranyaka Upanisad, both of which were later authorities, gave to the Puranas as holy a position as the Vedas. Between 600 and 300 B.G., when Apastamba had ended his life, the Puranas, or the better part of them, had been in vogue, because we find the Purāņas quoted in the Apastamba Dharmasûtra.

But we are concerned with the Vayu and the Siva Purāņas, of which the former one is much the earlier. The Vayu is one of the most ancient of the Puranas. Vayu, the Wind, was no Purana-Deity. He could not be given any form. The flag alone, which moved, proved his objective emblem. How Vayu as a Vedic god was being gradually replaced by formed deities like Śiva, Visnu and Agni, principally occupies the space in this Purana. It marked the bridge between the Vedic and the Paurāṇic cultures. The social cause why the new form of literature known as the Purāņas at all came into being supports our previous views regarding the changing Vedic and Brahmanical society in India. These changes, we said, were due to (a) the rise of the heretical Jainist and Buddhist forms, and (b) the periodical insurge of non-Indian Aryan and non-Aryan races into the cultural body of India. Brāhmaṇical systems had been fading away against foreign impacts. Moreover, the post-Buddha social conditions did not give back to the Brāhmaṇical domination the power it had once enjoyed. The new trends were more permissive, and the entire arrangement of Vedic caste-division was in jeopardy. New Smṛtis, Purānas, Grhya Sûtras attempted to lay down further rigidities, but had to evolve a thousand ways through which the powerful foreign trends, most of them supported by the force of arms, could be accommodated, up to a point! Thus came the time of the complex mosaic of the caste zig-zags, and their tenuous connections with heredity. All of it concerned 'purity of blood'; the criterion of Guna and Prarabdha (Karma) had become obsolete.

"Besides the staunch followers of the religious systems, there was another considerable class of people who were rather of a mixed type with a synthetic attitude of mind."4a This was the time also for the emergence of a thousand deities, for whom passages and chapters were being incorporated within the body of the Puranas; even new Purāņas were being written; and a number of Upapurānas came into being, all dedicated to the task of establishing such gods and goddesses who could displace the Vedic gods, and make room for them. On the one hand these sec- tarian deities received the highest homage through the Bhakti system, and on the other hand the systems of Samkhya and Vedanta were also upheld with utmost vigour. This accounts not only for the Tevaram, the Agama and the Pañcarātra literature, but also for the complex abstractions of the intellectual hair-splittings of Samkara, Rāmānuja, Vallabha and Madhava on the one hand, and Vasugupta, Bhaskara, Kṣemaraja and Abhinava- gupta on the other.

The rise of the other systems and forms proved fatal to the Brahmanical system. The Vedic works of the time, up to the time of Manu, envisage this gradual decay until the Vedic Yajñas were completely pushed out by the more permissive Agamic ways. This was the Bhakti way.

"The various sects and systems of religion created an atmosphere which did not in an orthodox way conform to Vedic or Brāhmaṇical ideals. This atmosphere was further disturbed by the advent of casteless foreigners such as the Greeks, Śakas, Palhavas, Kuṣaṇas, and Abhiras, who founded extensive kingdoms and settled in this country. Though these foreigners accepted Buddhism, Saivism or Vaisnavism and were soon Indianised, there non-Brāhmaṇic manners and customs could not but influence the people, specially their brothers in faith. Most of these alien tribes being originally nomadic, can be expected to have had a variable standard of morality which must have affected the people living around them."4b The social fabric must have been seriously disturbed to the very roots; and the new faiths which accommodated the emotive trends, and accepted some of the forms of image worship, alone by their liberal interpretation of the Sastras and the Vedas kept alive the ancient Sanatana system of the Vedas. The Agamas are thus saturated with Bhakti; but they also retain within their emotive language some of the spiritual sublimi- ties which Yoga and Vedanta aim at. The devotee's place, apropos of the deity, was as secured as the Brāhmaṇical sage well-versed in the Vedic rites.

Vayu Purāna gives a rather detailed indication about this change. This basic book on Saivism refers both to the Mahabharata and Hari- vamsa; although some of its chapters were added later, mainly this Purana keeps its form intact. In the beginning of the 7th cent. it was a popular source for the Pasupatas. Vayu, Brahma, and MärkandeyaPurānas deal with Siva and Sakti worship.

Agama Rites

The Agamas have been divided into three classes. These are the Vaisnava, the Sakta and the Saiva. In this way they between them accommodate the Vedas and the Tantras. This accommodation is the greatest contribution of the Agamas. The next contribution is, of course, its Bhakti spirit, which brings within the Hindu fold all the people, caste as well as non-caste. Considering that individuals are conducted by their innate Gunas, the Agamas make room for all types. Any individual could follow the Agamic way.

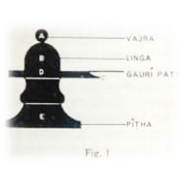

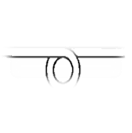

Agamic rites believe in the stages of Patanjali. Thus Yama, Niyama, Asana, Prāṇāyāma, Pratyāhāra, Dhyana, Dharaṇa are prescribed to reach Samadhi or Tadgati. The names differ at times, like Sila and Acara, Sevä and Ārati, Salokya, Samipya, Sarûpya, Sayujya and Tadgati. But the structure on the whole remains intact. Agamas however, recommend the Vigraha (Image), either in the iconic forms (Salagrama: Śiva Linga) or in the anthropomorphic form; and they also recommend a complete dedication to these Vigrahas as a part and parcel of the self.

Śalagrama is the Arûpa (abstract) aspect of the Deity; and its Sarûpa (Image) aspect is represented by the image of Visnu in the Anantaśayana Mûrti. We have not to concern with this murti now. We have to deal with the Śiva images as divined by the Dhyana (Spiritual insight) of the Agamic sages. The Arûpa Siva image is, of course, the Linga-murti, and its Sarûpa Mûrti is Tamomaya (Dark) Śiva consorting with Sakti. Śiva represents here the Yogi form. He is very popular with the Yogis, for whom He is Işta Devata; and the five-lettered Namah Sivaya is the Mantra form of this concept.

Thus for the Agamas the Sattva in Mûrti (Image) is Visņu; the Tamas in Mûrti is Siva; and the Rajas in Mûrti is Prakṛti, Durgā, Uma or Mahiṣamardini. The forms this Agama worship takes are known as Japa (chantings), Homa (Fire offerings); and Tarpana (worship with water, flower, food, etc.). Śiva Japa is: 'Namah Sivaya'; Visņu Japa is: 'Namo Nārāyaṇāya'; and Sakti Japa is: 'Ka Ai La Hrim, Ha Sa Ka Ha La Hrim, Sa Ka La Hrim'. Together with Präṇāyāma this is the Mantra-japa which leads to Siddhi (final success). Homa, which is reminiscent of the Vedic sacrifice, is done by offering 'ghee' in fire. Except in the case of Ganapati-worship it is very rare to do Homa in the course of Agama Vidhi. The last, Tarpana form is the most popular with the temple devotees. They offer flower, water, incense, lamps and anything else for food. This is the general pattern followed in all the Hindu temples; and this, of course, shows a large deviation from the early Vedic rites. All this isAgama.

Samkara explains these offerings in the following manner: Puruşa, the all pervading, himself is Bhāgavata (that is to say that the immanent essence of totality is itself congealed into the deity-form), the unqualified in the qualified form. Hence the image or the Vigraha is fit to be wor- shipped. In fact, at the time of the actual worship the worshipper conceives himself as the deity; without conceiving of this oneness there is no symphonical harmony created for offering an object to an object. Subjectivity alone could lead to the absolute.

Before finishing the topic on Agamas let us indulge in a rather long quotation from Dr. Hajra:

"Men may be grouped into three classes: those in whom the faculty of intellect and reasoning is dominant; those in whom emotion plays the highest role; and those that are controlled by their impulses and instincts. To those who belong to the first group, abstract thinking is easy, and they find satisfaction only in rational philosophy. This class is, naturally, a small group. For them ritualistic ceremonial religion is not suited; in other words, the members of this group are not Adhikarins (competents) for ritualistic religions. The last group is composed of children and those with childish mentality. They cannot think; nor are their emotions developed. They can be trained to follow a routine which, in due course, may help them to enjoy a form of vegetative satisfaction, to borrow a term from biology. As children grow up, and acquire emotional factors and capacity to think, the permanent members of this group are few and limited to those of lower mental capacity. The bulk of humanity lies between these two, forming the second or the intermediary group. In them emotion predominates; they are also capable of abstract thinking, but to a limited extent; and most of them would also require material and mechanical measures to stimulate their emotions to the desired strength. Bhakti Märga or the emotional way of realisation of God is for them. And Agama ritualism is designed to satisfy the needs of this class. The most important thing to understand in Hinduism is that everything taught there is not intended for everybody; there is no definite question of suitability, or Adhikari Bhāva. The greatness of Hinduism lies in the fact that it supplies forms, methods, and measures to suit all possible types of men."4c

Agamas: Revealed Texts

It is remarkable that Saivism in Kashmir, as well as in the Deccan claims to derive its authority from the Agamas. Both the forms claim the Agamas as being independent of the Vedas.

The Agamas which are said to have been propagated by Vasudeva,are also claimed to have been revealed by Siva (the Father) to Śiva (the Mother), or vice versa. As such, these are texts revealed to seers directly from the Godhead. In other words their authority is derived from inspirational experience, and no other. It is remarkable that the laws are recorded in the form of a dialogue. Most records that different prophets have left, follow this form. Plato's dialogues, although not pro- phetic or mystic, follow this convention. The Bible makes use of such phrases as, "and the Lord said unto Moses, 'Thou shalt not'," etc.; so in the Buddhist texts,-"The Lord spake". In the Buddhist texts or in Plato's dialogues or in Srimad Bhagvad Gita, it was a physical being who was held responsible for talking to another, who for the time being was inspirationally attuned. "Thus Spake Zarathustra" has become a familiar phrase, thanks to Nietzche. That accounts for Zoroastrianism. The chronicler attempted, thereby, to maintain a glimpse of some historical perspective. Mystically explained, such texts of 'Revealed Utterances' hold much of the Mystic Truths. The Revealer reveals what is beyond personal training and education. Unless spiritually inspired in content and form the compositions of the Revelations bear no logic with the mental preparation of their authors. Such revelations are only plausible in the mystic sense. The Vedas are known to have recorded truths as 'Realised' by the 'Author-Seer'. They are not composed by skillful authorship; but by the virtue of transcendental transmission of sublime truths. In perfection of forms and content they appear to be beyond human achieve- ment. Hence the Vedas are celebrated as Apauruşeya, trans-corporated, 'Realised'. Hence, they are known as the 'Vedas', i.e., Truths Realised. Revealed Texts are not peculiar to the Vedic traditions. All religious scriptures more or less claim 'Revealed' inspirations. Some of these, like the Vedas, are said to be directed without any intervention. Some, like the Koran or the Mosaic Laws, have come to us through a specially chosen intermediary. Yet some others have been recorded as dialogues. The recorded texts of the Buddha-canon, the new Testaments belong to the last category.

The Puranas and the Agamas have basically followed this method. Such is also the pattern followed by the Epics, the Mahabharata and the Rāmāyaṇa. All of these are 'narrated' texts. The peculiarity of the Agamas, as distinct from the Purānas and the great Epics, is that the dialogue in the Agamas are contained between Siva and His Consort Pārvati (Śiva) Herself. It is a dialogue between the Positive and Negative aspects of complete knowledge, a Female-Male team to produce a totality.

Therefore, in a sense, the Agamas could be described as the Revealed Texts of the first category. Revealed as they are, the Siddhantins try to relate the Agamas to the Vedic text. This gives the Agamas the addedvalues of reconcilement, and authoritative verification. The Siddhantins accept the Vedas as authority. The Trika finds the Agamas quite enough for their own reference.

The Agamas are traditionally referred to the Sangam Age in Tamil literature which go back to a hoary past. Historically, however, the age has been fixed by Dr. V. R. R. Dikshitar and Dr. M. A. Mehendale as ranging between 500 B.C. and 500 A.D. But there are strong opinions in favour of placing the earliest Sangam, in the available forms at about 3000 B.C. at the least. The present available forms, of course, are much later in date than the tradition they record. In any case the origin of the Sangam, whether viewed traditionally or historically favours independent growth without disowning Vedic contacts. How far independent it is, is to be examined.

Adiyars, Tevarams and Acaryas

The origins of the Agamas, and therefore of Saivism, relate to the Dravids and Tamils of the Deccan. The earliest development of Saivism is traced to the Adiyars and the Acaryas. The sixty-three canonical saints, known as the Adiyars, illustrated by their writings the spiritual distinctions of Saivism. The first four saints composed Siva-hymns known as Tevarams, emotionally inspired, spiritually sustained, and universally appreciated as poems of a sublime content. The Tevaram is considered to be the honoured treasure of the Saivic texts. But the Philosophical sub- stances of Saivism were expounded later by the Acaryas or teachers such as Moykanda-deva, Arundi-Śivacārya, Maraujñam-Sambandha and Umapati Sivācārya. The exposition of the Siddhanta system principally rests with them.

Siddhanta

As in the case of the Agamas, here we take a quick glance at the other orthodox form of Saivism: the Siddhanta. We will reserve for a later chapter a more elaborate treatment of the Agama metaphysics.

Saiva Siddhanta is categorised into three principal concepts of Pati (Lord), Pasa (Rope or string for trapping) and Pasu (animal). Pati is the Lord, the Ultimate Reality; perfecting knowledge; Paśu is the material being; Pasa is the ignorance of the material being, because it ties it, as in a trap, to the unreal, so that the Pati is deprived of its real consciousness to feel one with the cosmic consciousness.

The Siddhantins simplify the problem itself in order to provide a simple solution. The problem is reduced to extreme simplicity. Beings given, a source or a Primal Cause of the being becomes incontrovertiblyimperative. The Primal Cause in this way becomes the Primal Origin of Beings. Why then is there any difficulty to know the nature of Primal Origin? Why and how is the 'Being' kept so disengaged from its source when it is so difficult to recall and remember our pre-natal state? When does such an exercise appear to be even irrelevant and inconsequential? Why the Cause of Creation is not obvious? In other words, why does the cause of 'Being' appear to suffer from an inertia, as it were, in its attempts to relate its existence, and the purpose of existence, to the cause of its existence? Unless the cause of 'Being' is appreciated, the purpose of 'Being' cannot be comprehended. An uncomprehended continuity of existence is no better than a blindman's buff sort of living. Whereas such a state of impotent acceptance could be imagined in inert beings, in conscious beings the same state would indicate a depraved state of inertia, an innate indisposition to knowledge, or Tamas. It is this Tamas (Darkness, as opposed to Light, which is Sattva) which, as ignorance, creates dullness, drabness, inertia to intellect and will. Consciousness, which by nature should be crystal-clear, confronts a false cover. It is reduced to an opaque state through which light cannot penetrate. Hence it becomes imperative for the cultivation of knowledge to dispel this Tamas. Such a complex state of confusion in consciousness is created by these attachments and ties keep bound to surrounding objects through artificial correlates. It binds the apparent to the apparent; and keeps the fundamental away. Gradually the mind, accustomed to the torpor, does not even bother to seek the fundamental. Ignorance and false attachments, together, form 'the Bonds' or the Pasa. Therefore, the only reasonable way out is to cut away the Bonds. The Vedas say Pasan-s- chindhi (cut the traps).

The Pati, Pāśa and Paśu, a triumvirate, make the Siddhanta a philosophy of pluralistic realism. 'Hara' is the way to reach the first Cause of Beings, i.e., Śiva. 'Hara' means 'remove'. The Hara-way is the way of the removal of Pāśa, or ignorance. Without Hara's favour, and without cutting the trap, the removal of ignorance is impossible.

All beings are results of 'Anu' or atom, a product of pure energy and impure inactivity, i.e., gross matter. Streams of these impurities as 'āṇavamala', atomic impurities, spiritually polluted substances, appear as 'beings'. (Students of nuclear physics would discover the underlying truth of this stand in the process of discovering the origin of matter). 'Hara' which means 'remove' or 'make disappear', is invoked with the prayer of removing the impurities of beings, so that pure energy, the Real-Cause in its essence, is realised. Thus 'Hara' becomes the Primal Cause.

Pasa: Obstructions

The essence of perceiving this Primal Cause supersedes all effects. This is Hara, Siva, the Lord or God. He is the creator in the sense that in relation to all that is created, the concept of a creator suggests itself automatically and irresistibly. Human understanding is limited to personal capacity, which in its turn is related to experience, which, to begin with, is naturally limited. Yet the fact is that by nature human capacity is unlimited. The potential limitlessness of human capacity becomes limited in individuals in accordance with the person's innate unique individualism which is formed by the proportion of the 'Gunas' inherent in the beings. These impose restrictions on different strata of personality -the personality that naturally seeks purity and peace, yet gets not; the personality that lies apathetic, and refuses, and thereby learns not, because it remains ignorant on account of the inertia acquired through disguise. As a result, mind remains unreceptive and impenetrable. These three-in-one feature of each personality, i.e., the personality that remains unreceptive is the chief distinguishing characteristic of all matter-in-being, from a grain to a star, from an idiot to a seer. In proportion to the level of consciousness attained through a purposive effort, and through one's application towards winning the objective, each being differs from another. Consciousness is the one enveloping expression of the Supreme Cause; and in proportion to its 'Will' to awake or not to awake, does it indicate its purity of substance. Freedom from the Bonds depends on elimination of the Gunas. Gunas could be eliminated by a Free-Will alone.

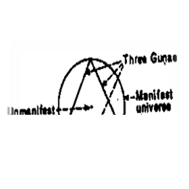

Gunas

What then are the Gunas? We had occasion to explain the Gunas casually in another context. But the concept calls for more clarification. Guna is Will's Modes of progress, ranging from Light to Darkness. All substance has a pure state; an impure state; and a state where pure and impure are in a state of flux. The pure is Sattva; the impure is Tamas: and the intermediary state in flux is Rajas. The most enlightened of these bonds is Sattva, which leads to perfect peace and bliss. The ever- striving, agitating, unpeaceful state of personality is due to Rajas; and the unagitating slothful ignorant state of personality is due to Tamas. All personalities have been categorised into three divisions according to the volitional impetus inherent in the nature of the being. In this way one category is called spiritual (a category attainable by human consciousness alone); the second category is mundane (a category that involves all beings having life); and the third category is ignorant (a categorywhere effortlessness is the chief characteristic). Sattva is Progress; Rajas is Activity; Tamas is Retardation or Regress. Sattva, Rajas and Tamas are the 'bonds' (Gunas) that keep the Pati, the Supreme, away from an individual's full realisation. Hara removes the bonds, by removing the impurities. In order to have a full experience of a beatific realisation one must exceed even the bond of Sattva.

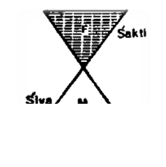

We have been talking in terms of the Cause, and the Caused. We have to, because of the limitations of the human language and power of comprehension. Though we are talking of the Cause and the Caused as two, yet it is defective to consider Śiva, the Caused, and Sakti, the Primal There is no duality. The Cause as two. In reality these are not two. Cause and the Caused in the final analysis are but two in conceptual classification alone. It is so termed in the interest of conceptual facility. (The two are really one, like the Moon and the moonlight.) Human concepts, too, are limited by Gunas, to begin with. Till all impurities are removed the Oneness of the two could not be entirely realised. So long as we cannot penetrate that area, we have only to talk; and as long as we talk, we have to talk in terms of 'More-than-one'. The One is to be Realised and cannot be talked of. Till it is realised, one has got to talk about it in human language.

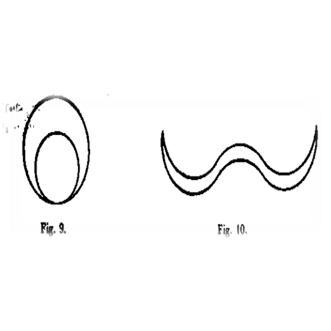

Realisation of bliss (Anandam) is an experience beyond the scope of speech. The realised actually experiences this linguistic duality just as one single experience. The Yogî Seer Ramakrishna illustrates the point by a gram-seed. The two halves of the seed are enclosed as one within the shell. The shell is Maya. It is, and is not in the sense that the 'two' within is, and is not; because the 'Two' are really One. The 'Life' of the seed, i.e., its generative substance and principle, is sustained by the apparent two-ness of the Real One, which is enveloped within a shell. The shell is Māyā (Because it is due to the cover of the shell that the two halves appear as, two, and hide the face of oneness); the two halves are Śiva's static state; Śiva, unnoticed, activises the generative property enveloped by the two lobes. The entire underlying principle of this unified activity is the Prapanca (the manifest world form). One emanates from, and stays in the other at the same time. It is both inactive and active, for such is the nature of matter, in its final analysis, that in it both activity and inactivity are inherent. Activity is potentially dormant in matter, yet its mutative cycle of change is operative. Look at the 'lobes' of the gram; inactive. Look at the sprouting gram, active. Nuclear physics, too, while defining the relation of electrons to protons, emphasises the conceptual existence with reference to atom. The final explanation is still mute to science.

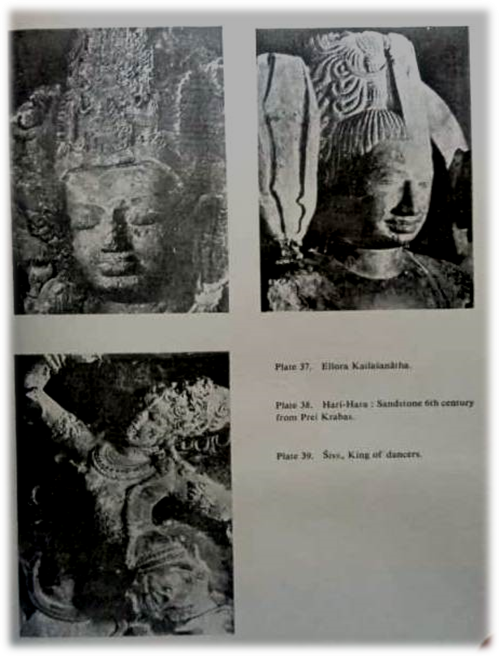

Hermaphrodites: Ardhanarisvara

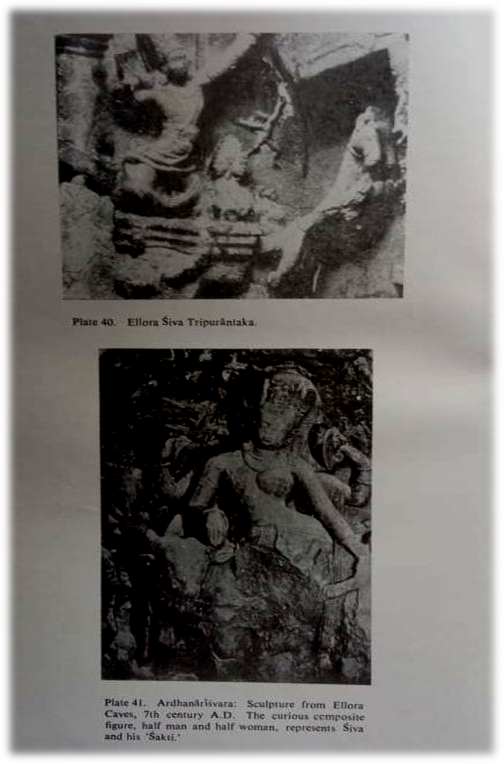

The two aspects of activity, active-activity and inactive-activity are known popularly as negative and positive respectively. Mathematics accepts the Negative as much a quantity as the Positive. This in meta- physical concept is termed as Sakti and Siva respectively, so the same two aspects again for the convenience of the limited power of human concept, are also known as female and male; but only as concepts, not as genders as we know them in the empirical sense. Therefore the Saiva Siddhantins have evolved the half-male, half-female (or, half-Śiva and half-Vişnu) iconographical representation of this idea in the celebrated, or else much abused, 'half-male half-female' (Ardhanari'svara) image (see Plates 38, 41). Thus the Primal Cause is a composite concept of Power and Form. It is significant that in Sanskrt the word Siva could be used as masculine, feminine, or neuter gender. The 'Cause' is 'It-She-He' all combined. No single gender is assignable to it. Concepts are abstract, and have no gender. For adoration alone such concepts are reduced to Image forms. Some choose a Father-image; some a Mother. This again depends on the matriarchal or patriarchal culture-form. We have discussed this in the first chapter and in the chapter on the Mother. Thus a Great Agama sage says, "Behold; the male, the female and the neuter in One image." We are told that in nuclear physics too an atom-structure is a composite of electron-proton-neutron. This abstract concept is the very antipodes and antethesis of the primitive fertility cult of which Phal- licism is an expression; and which is mistakenly confused with Saivism. Hindu metaphysics, may this be remembered, throughout its long tradition maintains this concept of 'two-in-one' as a treasured postulate.5 The images, to illustrate idealistically this postulate, are also idealistic, as has been shown in our plate. Such images are quite distinct from the realistic (physically erotic) images sculptored during the Greek and Roman times, at least one of which is a treasured specimen preserved in the Louvre, Paris.

So far about the bi-sexual image. What about the three-in-one images so high-lighted in the photographed expressions from Ellora, Elephanta and other ancient Saiva shrines?

Three-in-One

As in the case of the two-in-one Ardhanariśvara, so the concept of the three-in-one image, the Trimurti, has provoked minds unused to Hindu images, and led them to regard these as grotesque phantasmagoria. Of all types of fanaticism that of the conceited-wise is the most detrimental to clear thinking. The concept of Ardhanariśvara represents the conceptof the emergence of Being from the Matter-Energy state of evolution; and the concept of Trimurti represents the functional aspect of the matter in relation to being. Of course, this concept of finding in one body the cause of the matter, the caused in the matter and the neutral witness, reminds one of the symbols that the physicist uses like, +,- and 0, which indicate proton, electron and neutron. The Atom is the first 'Being' in the material world. It contains properties of (a) the energy energised, and abides by the law of functioning; (b) the actor, the acted and the witness; (c) creativity, stability and the neutral blank; and (d) the beginning, the middle, and the end (where the end and the beginning meet at a neutral point). This concept of matter, or atom is found symbo- This Trimurti lised in the image-representation known as Trimurti. is known as the aspects of Srsti, Sthiti, and Pralaya, represented by images known as Brahma, Visnu and Siva. No one is a unit without the other two. It is an imaged statement of the cyclic functioning of the Life-force within the World phenomenon. The functional energy which assumes different expressions, with different effects permeates and sur- charges the cosmic egg (Brahmanda) floating in an ocean of conscious Will. Due to the indeterminate imbalance of the gunas, evolutes assume different expressions, with different effects and consequences. Yet cosmically speaking all this, together, is a Whole, Brahmanda. Lest the variegated aspects of functional expressions delude the mind, and take the variations as different, the three-in-one form (Trimurti) images the idea in concrete shape. These functions are (a) emergence, (b) progress, and (c) disintegration; in other words, Creation, Sustenance and Dissolu- tion. Throughout, the entire process is one of Mutation, which disinte- grates to integrate. Lest by any chance-misconception the three are taken as three different units, and not as aspects of one single unit, as a precautionary measure, the three are put together into one figure. This is the Trimurti. It is adored as the manifestation of the true Rudra, the Red one, the terrible one (the hot heat of disintegration). He is not really so terrible, if one considers it entirely. "Rudra is truly one, for the knower of Brahma does not admit the existence of a second. He dwells as the inner Self of every being. After having created all the worlds, He, their Protector, takes them back into Himself at the end of Time."6

Thus, bonds do not bind the Supreme. He is freedom of bliss itself. So Siva is unbonded (Nirguna), free of impurities (Nirmala), beyond all 'that' (Tatpara) and incomparable (Asāmānya). Siva cannot be des- cribed by language (anirvacanîya). In the field of consciousness he neither is the awakened state (Jagrat), nor the dream state (Svapna), nor the sleeping state (Suşupti). He is the fourth state, the sublime (para) state, the Beyond (turiya) state. We note here that the Siddhanta concept of Siva, the Brahma concept of the Vedanta, the Puruşa of Samkhya almostconvey one and the same idea as Plato, Socrates or Pythagoras attempted to mean. As such Saivism is the extreme of Idealistic realism. It is a blunder to equate it with any cult, and the least with the fertility cult, or phallicism.

(a) The Spiritual Eight

Included in the Siva concept of Siddhanta is the graduated concept of spiritual attributes. "Having no sense organs it is unaffected by the bonds cast by senses." These attributes are eight: independence, purity, self knowledge, omniscience, freedom from impurities (mala), boundless benevolence, omnipotence, and bliss. He is Cit: Sat, i.e. a concept of reality which is entirely conscious. As such part-consciousness, or fettered consciousness cannot be fully aware of it, in the sense that pure consciousness is just one stream, one field, one overwhelming experience. Siva is totality. It is not a fraction.

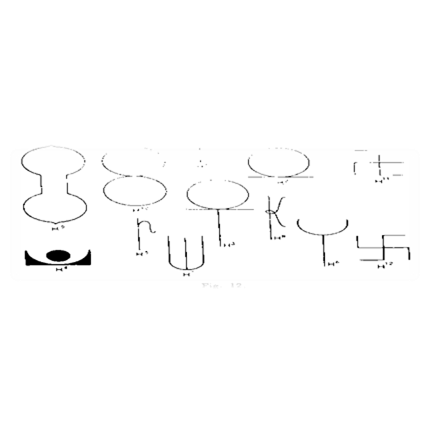

(b) The Perceptual Eight

Śiva or Pati is both immanent and transcendent. His transcendental aspects have been described above. His immanent aspects, which are altogether expressed in eight perceptual forms, are as follows: Earth, Water, Air, Fire, Sky, Sun, the Moon and the Sentient man. This group of eight, together with the previous group of eight, make eight an esoteric numerical in Saivism. Thus Śiva is known as the eight-formed one, or the eight-in-one (Aṣṭamûrti) which sometime is iconographically represented as one with eight heads, or eight hands.

Aṣṭa (eight) Vajras (weapons) are to be united for emancipation. (cf., the legend of the liberation of Aśvini in the Dandiparvam, an appendix to the Mahabharata.) Asta (eight) Dhatus (metals) are melted to mould a metal statue of Siva, or of Sakti, as Kalî or Durgā. The Yoga system is known to have eight parts, Aṣṭānga Yoga.

The Five Principles

Śiva has been described as having the three functions of integration, sustenance and disintegration. Whereas this is true about the conceptual and transcendental world, in the immanent world two more functions complete the correlates between the transcendental and the immanent. These are functions of Grace and Obscurity, i.e., Expression and non- Expression of Grace; Grace-descending, and Grace withheld.

The Saiva concept of Grace might very well bear comparison with the later evolution of the concept amongst the Essines and the Christians. What would remain of Christianity once the concept of Grace is takenaway from it? The great and original contribution that Jesus made over and above the doctrine of John the Baptist was the freshness of his concept of Grace and Love: Yet, Grace as a divine immanent concept has been the original contribution of the Saivas. It is not in vain, really that there exists amongst some of the sects of important and orthodox Hindu ascetics a fond faith that Jesus Christ as a disciple of John the Baptist was a living example of a Saiva Brahmacarî Sannyasî, i.e., an ascetic mendicant, who was an indisputable and illustrious example of mind over body, as well as of the Saiva-Principle of Grace. Egypt and the Egyptians were very conversant with a similar creed as we will see.

Blessed art thou, O Lord, God of mercy and abundant Grace,

For thou hast made known Thy wisdom to me

That I should recount Thy marvellous deeds,

Keeping silence neither by day nor by night : For I have trusted in thy Grace.

In thy great goodness.

(Hymn from Dead Sea Scrolls-C. Vermes-Pelican, p. 16.)

Philosophically the Siddhantins consider 'Existence distinct from Sakti' in the same manner as they consider 'Existence distinct from consciousness'; or Sat distinct from Git. Śaiva Siddhanta speaks of Siva, the Pati, having the five functions of obscuration (Tirodhāna), creation (Sṛşti), preservation (Sthiti), destructions (Samhāra) and grace (Anu- graha). Hence Siva image has five faces representing Five Facets. We shall elaborate on these a little later. To realise the facets let us recall that the same gracious sun that causes the blossoms to bloom and sets aglow the countryside with splashes of colours is also responsible for the decay of the thousand other petals that drop and die. As flowers they die, but as fruit they preserve the seed of the life-cycle. Life's very growth is a guarantee for its race towards the end. He, who considers these as two different functions, is confused. He is ever and ever merged in a Buddhistic melancholy of suffering and sorrow. Happiness or peace is his who regards these as the aspects of the one and the same Grace. It is Śiva that unmoved moves all; remaining unaltered, presides over all alterations; remaining unaffected, witnesses all affections. Such is the nature of the Absolute Truth and Reality that is Śiva.

Incarnation

Therefore, it stands to reason that Siddhantins insist that Śiva could not be subjected to the rigours and humiliations of birth and death in the worldly way. Śiva is not born to die, or is not subject to alter with thealterations of time. Hence reincarnation cannot happen to Śiva. Although reincarnation is ruled out in Saivism, so far as Siva is concerned, it is however held to be possible for a Saiva mystic to realise Śiva in any particular form in which the devotee is accustomed to have thought of Him. Such mystical transfiguration is not unknown to spiritual history. It is a case of the cosmic consciousness crystallizing before the perceptual apprehension of the realised being. Transfiguration is not to be confused with incarnation. God cannot be subjected to birth and death, although Godliness could assume a transfigured state with respect to the sub- limated. The perceptual capacity of a Dhruva, a Dattatreya, a St. John on the Cross, or a St. Bernadette enjoyed much more awareness. This was due to their spiritual personality. Siva appears to the mystic devout as and when the intense demand of the soul makes transfigurations irresistible; but the particular form that Siva would then assume, would depend on the habitual form in which He had been conceived of by the inner spirit of the devotees. "God does not take the body in the way a trans- migrating soul does. This does not mean that God does not appear in bodily form. He does assume the form in which he is worshipped by His devotee and also in the forms that are required to save the soul. But all such forms are not made of matter; they are the expressions of His Grace.""

Speaking of incarnations, Śiva-philosophers regard the transcendentalised in flesh as an incarnation. This preference is inspired by the sense that Grace has davned on a person in its fullness. Such a person is an ascended being, a Saint. The ascension of Jesus, regarded in this ethereal and cosmically unified state is an honoured faith amongst very many Hindu devouts. Such an assumption enjoys, however, a traditional mystic support.

Apart from the incarnation of Spirit into form, the Saiva ascetics in general take pleasure in assuming all possible physical embellishments that distinguish Siva from other Vedic gods. There is a sect in India known as the Nathas who bear, or try to bear, all the embellishments of Siva on their bodies. Besides them, ascetics in general, whose ideal is Śiva, are known for using skin of animals as wear, straw-strings as belts, a trident or a spear as staff, a shell or a simple bowl as their only vessel. They wear matted locks; smear their bodies with ash; speak in a high voice; assume rough and ready ways; and honour abstentions from passionate sensuous behaviour. They seek solitude; eat vegetarian food; avoid contacts and congregations, and keep to the woods.

The Pasu

The next important link of the Saiva Siddhanta is the Paśu, i.e., the 'being' itself. What or who is this 'Being'? A passionate, emotional,limited, qualified identity, known as an individual. This individual is identified, recognised, given a name and a class or category. The factors on which these distinctive differentials depend are many and various. Ultimately by this process the One appears to be many. But it is a delu- sion. All really, are the variants of the One real. As such, the distinctions are due to an obvious delusion of mind; it gives rise to an illusion in concept. It results in an irresistible mental projection which by its nature is unsteady and ever shifting. It is called Mäyä, which we have discussed in the previous chapter under Vedanta.8

Maya and Visrsti

Māyā, too, is a cause, as there is a cause to a mirage. The cause of the mirage is enrooted in a principle which is more real than the mirage. The same mirage is not the same from two different points, at two different times, if seen by two different persons. But the cause of the mirage re- mains the same. According to the theory of Satkāryavāda of the Siddhan- tins, Māyā is the material cause of the Universe. It creates an illusion of many-ness, when really there are not many."