Table of Contents

Life-Sketch of Swami Brahmananda

An Introduction to the Study of The Supreme Knowledge

The Quintessence of Spiritual Practice

|

We are happy to present to the spiritual seekers this book which is chiefly an anthology of selected writings of H.H. Sri Swami Brahmanandaji Maharaj, a senior Mahatma of Sivananda Ashram, who attained Mahasamadhi on 12th September, 2002. This valuable collection contains certain important works of Parama Poojya Swamiji Maharaj, which were published on earlier occasions in the form of small booklets for free distribution as Jnana Prasad. It is with this intention of preserving these valuable treatises that the present volume is being published.

Revered Swamiji’s writings are endowed with the clarity of an acute scholar and the profundity of a practical saint combined in one. Students of Vedanta will find this collection as a vademecum for constant recollection of the Vedantic verities.

May the choicest blessings of the Lord and the Brahma-vidya Gurus be upon all.

Shivanandanagar,

Rishi Panchami,

1st September 2003.

–THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY

यस्मिन् यतो यरहि येन च यस्य यस्मात् यस्मै यथा यदुता यस्त्वपरः परो वा,

भावः करोति विकारोति पृथक स्वभावः संचोदिस्तदखिलम् भवतः स्वरूपम्।

Yasmin yato yarhi yena ca yasya yasmaat yasmai yatha yaduta yastvaparh paro vaa,

Bhaavah karoti vikaroti pruthak svabhaavah sanchoditastadakhilam bhavatah svaroopam.

O Lord! Anyone who in any condition, for any reason, at anytime does anything or changes anything, whether it is good or bad, with whatever intentions good or evil, in whatever manner, unto anyone, through anyone, in relationship with anyone, influenced by anyone–all that is your own Self!

–Srimad Bhagavata Mahapuranam (VII-9-20)

POINTERS ON VEDANTA

SANTIMANTRA

(Taittiriya Upanishad II-I-I)

ॐ सह नववतु सह नौ भुनक्तु सह वीर्य करवावहै।

तेजस्वी नवधीतमस्तु, मा विद्विषावहै, ।।

ओम शांति! शांति! शांति! ।।

Om Saha Navavatu Saha Nau Bhunaktu Saha Viryam

Karavavahai. Tejasvi Navadhitamastu, Ma Vidvishavahai,

Om santi! santih! santih!

May He protect us both (the teacher and the taught) together (by revealing Knowledge). May He protect us both (by vouchsafing the result of Knowledge). May we attain vigour together? Let what we study be invigorating. May we not cavil at each other? Peace! Peace! Peace!

GURU STOTRAS

ॐ नमो ब्रह्मादिभ्यो ब्रह्मविद्यासम्प्रदाय कर्तृभ्यो

वंशऋषिभ्यो महद्भ्यो नमो गुरुभ्यः ॥ १ ॥

सर्वोपप्लवरहितः प्रज्ञानघनः प्रत्यगर्थो ब्रह्मैवाहमस्मि ॥२॥

ॐ नारायणं पद्मभवं वसिष्ठं शक्तिं च तत्पुत्र- पराशरं च।

व्यासं शुकं गौडपदं महान्तं गोविन्दयोगीन्द्रमथास्य शिष्यम् । श्रीशङ्कराचार्यमथास्य पद्मपादं च हस्तामलकं च शिष्यम्।

तं तोटकं वार्तिककारम् वार्तिककारम् शिवानन्दमन्यानस्मगुरून्सन्तत- मानतोऽस्मि ॥३॥

श्रुतिस्मृतिपुराणानामालयं करुणालयम् ।

नमामि भगवत्पादं शङ्करं लोकशङ्करम् ॥४॥

शङ्करं शङ्कराचार्यं केशवं बादरायणम् ।

सुत्रभाष्यकृतौ वन्दे भगवन्तौ पुनः पुनः ॥५॥

ईश्वरो गुरुरात्मेति मूर्तिभेदविभागिने ।

व्योमवद्व्याप्तदेहाय दक्षिणामूर्तये नमः ॥६॥

1. Om Namo brahmadibhyo brahma-vidya- sampradayakartrbhyo vamsa-rshibhyo mahadbhyo namo gurubhyah.

2. Sarvopaplava- rahita prajnana-ghanah pratyag-artho brahmaiva'ham-asmi.

3. Om Narayanam padmabhavam vasishtham saktim cha tatputra-parasaram cha, vyasam sukam gaudapadam mahantam govinda-yogindram-atha'sya sishyam, sri sankaracharyam-atha'sya padmapadam cha hastamalakam cha sishyam, tam totakam vartikakaram sivanandam-anyan asmad-gurun santatam-anatosmi.

4. Sruti-smrti-purananam alayam karunalayam

Namami bhagavat-padam sankaram loka-sankaram.

5. Sankaram sankaracharyam kesavam badarayanam Sutra-bhashya-krtau vande bhagavantau punah punah.

6. Isvaro gurur-atmeti murti-bheda-vibhagine Vyomavad-vyapta-dehaya dakshinamurtaye namah.

1. Om, Obeisance to Lord Brahma and others, to the propounders of the supreme knowledge of Brahman, to the traditional line of Seers and Sages and to the great and the revered ones; obeisance to the Spiritual Masters. 2. I am Brahman who is free from all evil, who is a mass of Consciousness and the innermost essence in all.

3. I always offer my prostrations to the supreme Brahman, Lord Narayana, the creator Brahma born from the lotus, the great sage Vasishtha, Sakti and his son Parasara, Vyasa, Suka, the great Gaudapadacharya, Govindapada, the best among the Yogins, his disciple Sri Sankaracharya, then to his disciples Padmapadacharya, Hastamalakacharya, Totakacharya and Suresvar- acharya, the author of the gloss on the commentaries of his Master and Gurudev Sri Swami Sivanandaji Maharaj and all my other spiritual masters.

4. I bow down to Sri Sankaracharya who is the repository of all the Vedas, the Smrtis and the Puranas, the store-house of all compassion and whose feet are adorable and who is the bestower of all auspiciousness upon the whole world.

5. Obeisance to Sankaracharya who is Sankara himself and to Vyasa who is Narayana himself, the authors of the commentary on the Brahma Sutras and the Sutras themselves respectively.

6. Prostrations to that Supreme Lord in the form of Dakshinamurti, whose body is all pervasive like space and who manifests as God, Guru and the Atman, the apt difference among the three being only in name and form.

SIVA-MANASA-PUJA

(Sri Sankaracharya)

ॐ श्री गणेशाय नमः

रत्नैः कल्पितमासनं हिमजलैः स्नानं च दिव्याम्बरम्

नानारत्नविभूषितं मृगमदामोदाङ्कितं चन्दनम्।

जातीचम्पकबिल्वपत्ररचितं पुष्पं च धूपं तथा

दीपं देव दयानिधे पशुपते हृत्कल्पितं गृह्यताम्॥१॥

सौवर्णे नवरत्नखंडरचिते पात्रे घृतं पायसं

भक्ष्यं पञ्चविधं पयोदधियुतं रम्भाफल पानकम्।

शाकानामयुतं जलं रुचिकरं कर्पूरखण्डोज्जवलम्

ताम्बूलं मनसा मया विरचितं भक्त्या प्रभो स्वीकुरु ॥२॥

छत्रं चामरयोर्युगं व्यजनकं चादर्शकं निर्मलम्

वीणाभेरिमृदङ्गकाहलकलागीतं च नृत्यं तथा।

साष्टाङ्गं प्रणतिः स्तुतिर्बहुविधा ह्येतत् समस्तं मया

सङ्कल्पेन समर्पितं तव विभो पूजां गृहाण प्रभो ॥ ३ ॥

आत्मा त्वं गिरिजा मतिः सहचराः प्राणाः शरीरं गृहम्

पूजा ते विषयोपभोगरचना निद्रा समाधिस्थितिः।

सञ्चारः पदयोः प्रदक्षिणविधिः स्तोत्राणि सर्वा गिरो

यद्यत्कर्म करोमि तत्तदखिलं शम्भो तवाराधनम् ॥४॥

करचरणकृत वाक्कायज कर्मजं वा

श्रवणनयनज वा मानस वापराधम्।

विहितमविहितं वा सर्वमेतत् क्षमस्व

जय जय करुणाब्धे श्रीमहादेव शम्भो ॥५॥

Om Sri Ganesaya Namah

Ratnaih kalpitam-asanam hima-jalaih snanam cha divya'mbaram Nana-ratna vibhushitam mrga-mada'moda'nkitam chandanam Jati-champaka-bilva-patra-rachitam pushpam cha dhupam tatha Dipam deva daya-nidhe pasupate hrt-kalpitam grhyatam. (1)

Sauvarne nava-ratna-khanda-rachite patre ghrtam payasam Bhakshyam pancha-vidham payo-dadhi-yutam rambha-phalam Panakam

Sakanam-ayutam jalam ruchikaram karpura-khandojjvalam Tambulam manasa maya virachitam bhaktya prabho svikuru. (2)

Chhatram chamarayor-yugam vyajanakam cha'darsakam nirmalam

Vina-bheri-mrdanga-kahala-kala gitam cha nrtyam tatha

Sashtangam pranatih stutir-bahuvidha hyetat samastam maya

Sankalpena samarpitam tava vibho pujam grhana prabho. (3)

Atma tvam girija matih sahacharah pranah sariram grham

Puja te vishayopabhoga-rachana nidra Samadhi-sthitih

Sancharah padayoh pradakshina-vidhih stotrani sarva giro

Yadyat karma karomi tattad-akhilam sambho tava'radhanam. (4)

Kara-charana-krtam vakkayajam karmajam va

Sravana-nayanajam va manasam va'paradham

Vihitam-avihitam va Sarvam-etat kshamasva

Jaya jaya karunabdhe sri mahadeva sambho. (5)

1. A seat made of precious stones, a bath in delightfully cool water, a splendid apparel bedecked with various gems, sandal-paste perfumed with musk, jasmine and champaka flowers arranged upon Bilva leaves, incense as well as light-O Lord, thou ocean of mercy, do accept these offerings conceived in my mind to Thee, O Lord of creatures.

2. Clarified butter, milk porridge, the fivefold food, a cooling drink of milk and curds with plantains, vegetables of innumerable varieties, tasteful water and betel scented with camphor--all these food-offerings placed in golden vessels which are set with the nine precious jewels have I conceived in my mind out of love and devotion; do accept them, O Lord.

3. Chhatra (umbrella), a couple of Chamaras for fanning and a stainless mirror; music of the lute, kettledrum, Mridanga and Kahala and singing together with dancing; obeisance by prostration of the eight limbs of the body, various hymns and prayers--all these, O Supreme Ruler, I duly offer to Thee mentally; do accept my worship, O Almighty Lord.

Thou art (my) Atman; my intellect is Girija (the daughter of Himalaya and the consort of Siva); my sense-organs are Thy attendants; (this) body is Thy temple; ministering to the enjoyment of the objects of the senses is (my) worship to Thee; (my) sleep is Samadhi; all (my) moving about on foot is the rite of perambulation (walking round the deity); all the words (spoken) are hymns to Thee; whatever works I do, are Thy worship, O Sambhu (Giver of happiness).

5. Sins committed in action with the hands and feet, or by speech, or by the body, or by the ears and eyes or those done in thought--forgive all these sins whether of commission or omission. Glory be unto thee, Thou ocean of mercy! Glory be unto Thee, O Mahadeva (God of gods)! O Sambhu!

PARA PUJA

(Sri Sankaracharya)

अखण्डे सच्चिदानन्दे निर्विकल्पैकरूपिणि

स्थितेऽद्वितीयभावेऽपि कथं पूजा विधीयते ॥१॥

पूर्णस्यावाहनं कुत्र सर्वाधारस्य चासनम्।

स्वच्छस्य पाद्यमर्घ्यं च शुद्धस्याचमनं कुतः ॥२॥

निर्मलस्य कुतः स्नानं वासो विश्वोदरस्य च ।

अगोत्रस्य त्ववर्णस्य कुतस्तस्योपवीतकम् ॥३॥

निर्लेपस्य कुतो गन्धः पुष्पं निर्वासनस्य च।

निर्विशेषस्य का भूषा कोऽलङ्कारो निराकृतेः ॥४॥

निरञ्जनस्य किं धूपैर्दीपैर्वा सर्वसाक्षिणः ।

निजानन्दैकतृप्तस्य नैवेद्यं किं भवेदिह ॥५॥

विश्वानन्यितुस्तस्य किं ताम्बूलं प्रकल्पते।

स्वयंप्रकाशचिद्रूपो योऽसावर्कादिभासकः ॥ ६ ॥

प्रदक्षिणा ह्यनन्तस्य ह्यद्वयस्य कुतो नतिः।

वेदवाक्यैरवेद्यस्य कुतः स्तोत्रं विधीयते ॥७॥

स्वयं प्रकाशमानस्य कुतो नीराजनं विभोः ।

अन्तर्बहिश्च पूर्णस्य कथमुद्वासनं भवेत् ॥८॥

एवमेव परापूजा सर्वावस्थासु सर्वदा ।

एकबुद्ध्या तु देवेश विधेया ब्रह्मवित्तमैः ॥ ९ ॥

Akhande sachchidanande nirvikalpaika rupini

Sthite'dvitiya bhave'api katham puja vidhiyate. (1)

Purnasya'vahanam kutra sarva'dharasya cha'sanam

Svacchasya padyam arghyam cha suddhasya'chamanam kutah. (2)

Nirmalasya kutah snanam vaso visvodarasya cha

Agotrasya tvavarnasya kutastasyopavitakam. (3)

Nirlepasya kuto gandhah pushpam nirvasanasya cha

Nirviseshasya ka bhusha ko'lamkaro nirakrteh. (4)

Niranjanasya kim dhupair dipair-va sarva sakshinah

Nija'nandaika-trptasya naivedyam kim bhaved iha. (5)

Visvanandayitus-tasya kim tambulam prakalpate

Svayam-prakasa-chidrupo yo'savarkadi-bhasakah. (6)

Pradakshina hyanantasya hyadvayasya kuto natih

Veda-vakyair-avedyasya kutah stotram vidhiyate. (7)

Svayam-prakasmanasya kuto nirajanam vibhoh

Antar-bahischa purnasya katham udvasanam bhavet. (8)

Evam-eva para-puja sarva'vasthasu sarvada

Eka-buddhya tu devese vidheya brahma-vit-tamaih. (9)

To this undivided Whole, Existence-Knowledge Bliss-Absolute, free of all modifications of the mind, the one and the non-dual, how can Puja (worship), be prescribed! (1)

How can one perform the ritual of Avahana (invocation) for Him who is the Whole! How can one offer Asana (a seat) for Him in whom everything is seated! How can one offer Padya (water to wash the feet) and Arghya (water to wash the hands) to Him who is cleanliness itself! (2)

Where is Abhisheka (holy bath) for Him who is purity itself and similarly, how Vastram (clothe) can be offered to Him of whose body the whole Cosmos forms one part viz., the belly! What to speak of Upavitam (the sacred thread) to Him who has neither Gotra nor Varna (neither genus nor class)! (3)

How can we apply sweet smelling sandal (Chandana) on Him in whom nothing will stick! Where is the place for Pushpa (flowers) for Him who is free from all smell! To Him who is Nirvisesha (attributeless) what ornament can be offered! And as He is Nirakara (formless) who can adorn Him! (4)

Why the offering of incense to Him who is Niranjana (free from all taint and stain)! To the Sarva-sakshi (witness of all) to the Consciousness which illumines all, how can one offer Dipa (the waving of light)! As He is always Nijanandaika Trpta (contented with the Atmic bliss) where is the necessity for Naivedyam (offering of food)! (5)

Is there any meaning to offer Tambula (betel leaves, etc.,) to Him who is the source of joy to this whole universe and who is self-effulgent, whose form is Consciousness and who illumines these great luminaries like the sun and the moon! (6)

How to perform Pradakshina (perambulations) around Him who is the Infinite! How to perform Namaskara (reverential salutation) to Him who is non-dual Being! Who can chant Stotra (praise) when Vedas themselves are not able to speak anything about Him! (7)

How to offer Niranjana (waving of lights and camphor) to one who is Himself Self-effulgence! And how to do Udvasana (send-off with prayer to return) to Him who is the full inside and outside! (8)

Thus should great knowers of Brahman perform this Para Puja (transcendental worship) of the Lord always in all conditions with one-pointed mind. (9)

NIRVANA-SHATKAM

(Sri Sankaracharya)

मनोबुद्ध्यहङ्कारचित्तानि नाहं

न कर्णं न जिह्वा न च घ्राणनेत्रे ।

न च व्योम भूमिर्न तेजो न वायु-

श्चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहं शिवोऽहम् ॥१॥

न च प्राणसंज्ञो न वै पञ्चवायु

र्न वा सप्तधातुर्न वा पञ्चकोशः ।

न वाक् पाणिपादौ न चोपस्थपायू

चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहं शिवोऽहम् ॥ २ ॥

न मे द्वेषरागौ न मे लोभमोहौ

मदो नैव मे नैव मात्सर्यभावः ।

न धर्मो न चार्थो न कामो न मोक्ष-

श्चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहं शिवोऽहम् ॥ ३ ॥

न पुण्यं न पापं न सौख्यं न दुखं

न मन्त्रो न तीर्थं न वेदा न यज्ञाः ।

अहं भेजनं नैव भोज्यं न भोक्ता

चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहं शिवोऽहम् ॥४॥

न मृत्युर्नशङ्का न मे जातिभेदः

पिता नैव मे नैव माता च जन्म |

न बन्धुर्न मित्रं गुरुर्नैव शिष्य-

श्चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहं शिवोऽहम् ॥ ५ ॥

अहं निर्विकल्पो निराकाररूपो

विभुत्वाच्च सर्वत्र सर्वेन्द्रियाणाम् ।

न चासंगतं नैव मुक्तिर्न बन्ध-

श्चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहं शिवोऽहम् ॥ ६ ॥

Mano-buddhy-ahankara-chittani na'ham

na karnam na jihva na cha ghrana-netre

Na cha vyoma bhumir-na tejo na vayuh

chidananda-rupah sivo'ham sivo'ham. (1)

Na cha prana-samjno na vai pancha-vayur

na va sapta dhatur-na va pancha-kosah

Na vak-pani-padau na chopastha payu

chidananda-rupah sivo'ham sivo'ham. (2)

Na me dvesha-ragau na me lobha-mohau

mado naiva me naiva matsarya-bhavah

Na dharmo na chartho na kamo na mokshah

chidananda-rupah sivo'ham-sivo'ham. (3)

Na punyam na papam na saukhyam na dhukham

na mantro na tirtham na veda na yajnah

Aham bhojanam naiva bhojyam na bhokta

chidananda-rupah sivo'ham sivo'ham. (4)

Na mrtyur na sanka na me jati-bhedah

pita naiva me naiva mata cha Janma

Na bandhur na mitram gurur naiva sishyah

chidananda-rupah sivo'ham sivo'ham. (5)

Aham nirvikalpo nirakara-rupo

vibhut-vaccha sarvatra sarvendriyanam

na cha sangatam naiva muktir na bandhah

chidananda-rupah sivo'ham sivo'ham. (6)

1. I am not the mind, nor the intellect, neither the ego nor the subconscious; I am also not the ear, not the nose, not the eye; I am neither the ether nor the earth, neither the fire nor the air; I am the most auspicious Lord Siva in the form of Consciousness-Bliss.

2. I am not the vital force or its five subdivisions. I am also not the seven ingredients of the body or the five sheaths; I am neither the organ of speech nor the hand, nor the leg, neither the sex organ nor the anus; I am the most auspicious Lord Siva in the form of Consciousness-Bliss.

3. In me there is neither desire nor hatred, neither covetousness, nor delusion; neither pride nor jealousy; I have no aims of life (viz., righteousness, earning wealth, fulfilment of desire and liberation); I am the most auspicious Lord Siva in the form of Consciousness-Bliss.

4. In me there is neither merit nor sin, neither happiness nor unhappiness, there is neither Mantra for Japa nor holy waters, neither Veda nor sacrifice; I am neither the enjoyer nor the enjoyed nor the enjoyment; I am the most auspicious Lord Siva in the form of Consciousness-Bliss.

5. In me there is no doubt about death, no difference in the social status; I have neither father nor mother nor birth, neither relation nor friend, there is neither the Guru nor the disciple; I am the most auspicious Lord Siva in the form of Consciousness-Bliss.

6. I am changeless; I am formless; I am the Supreme, I am the all-pervasive Lord of all the sense organs everywhere; no attachment for me; for me there is neither bondage nor liberation; I am the most auspicious Lord Siva in the form of Consciousness-Bliss.

ALL THIS IS THE SUPREME TRUTH

(Sri Sadasiva Brahmendra Swami)

सर्वं ब्रह्ममयं रे रे ।

सर्वं ब्रह्ममयम् ॥१॥

किं वचनीयं किमवचनीयम् ।

किं रचनीयं किमरचनीयम् ॥ २ ॥ (सर्व... )

किं पठनीयम् किमपठनीयम् ।

किं भजनीयं किमभजनीयम् ॥ ३ ॥ (सर्व...)

किं बोद्धव्यं किमबोद्धव्यम् ।

किं भोक्तव्यं किमभोक्तव्यम् ॥४॥ (सर्व...)

सर्वत्र सदा हंसध्यानम् ।

कर्तव्यं भो मुक्तिनिधानाम् ॥ ५॥ (सर्वं...)

Sarvam brahma-mayam re re sarvam brahma mayam. (1)

Kim vachaniyam kim-avachaniyam

kim rachaniyam kim-arachaniyam. (2) (Sarvam...)

Kim pathaniyam kim apathaniyam

Kim bhajaniyam kim abhajaniyam. (3) (Sarvam...)

Kim boddhavyam kim-aboddhavyamdem

kim bhoktavyam kim-abhoktavyam. (4) (Sarvam...)

Sarvatra sada hamsa-dhyanam,

kartavyam bho mukti-nidhanam. (5) (Sarvam...)

Lo! Behold!

All this is the Absolute,

All this is the Absolute. (1)

What is there to speak!

What is there that should not be spoken!

What is there to write!

What is there that should not be written! (2)

What is there to study!

What is there that should not be studied!

What is there to worship!

What is there that should not be worshipped! (3)

What is there to know!

What is there which should not be known!

What is there to be experienced!

What is there which should not be experienced! (4)

O man, your duty is to meditate on the Self,

everywhere, at all times. It is the seat of Liberation. (5)

ASHTAVAKRA GITA

(II-11 to 14)

अहो अहं नमो मह्यं विनाशो यस्य नास्ति मे ।

ब्रह्मादिस्तम्बपर्यन्तं जगन्नाशेऽपि तिष्ठतः ॥ ११ ॥

अहो अहं नमो मह्यमेकोऽहं देहवानपि ।

क्वचिन्न गन्ता नागन्ता व्याप्य विश्वमवस्थितः॥१२॥

अहो अहं नमो मह्यं दक्षो नास्तीह मत्समः।

असंस्पृश्य शरीरेण येन विश्व चिरं धृतम् ॥१३॥

अहो अहं नमो मह्यं यस्य मे नास्ति किञ्चन ।

अथवा यस्य में सर्वं यद्वाङ्मनसगोचरम्॥१४॥

Aho aham namo mahyam vinaso yasya nasti me

Brahmadi-stamba-paryantam jagan-nase'pi tishthatah. (11)

Aho aham namo mahyam eko'ham dehavan-api

Kvachin-na ganta na'ganta vyapya visvam-avasthitah. (12)

Aho aham namo mahyam daksho nasti'ha mat-samah

Asamsprsya sarirena yena visvam chiram dhrtam. (13)

Aho aham namo mahyam yasya me nasti kinchana

Athava yasya me sarvam yad-vang-manasa-gocharam. (14)

Marvellous am I! Adoration to Myself, who survive even the destruction of the whole universe-from the Creator down to a blade of grass-and who know no decay too. (11)

Marvellous am I! Adoration to Myself who though with a body, am One, who neither go to nor come from anywhere but ever abide pervading the universe. (12)

Marvellous am I! Salutations to Myself! There is none known so competent as Me who am holding the universe eternally without touching it with My body. (13)

Marvellous am I! Prostrations to Myself who have nothing or all that which is accessible to speech and mind belongs to Me only. (14)

YOGA VASISHTHA

(l-i-1 to 3)

यतः सर्वाणि भूतानि प्रतिभान्ति स्थितानि च ।

यत्रैवोपशमं यान्ति तस्मै सत्यात्मने नमः ॥१॥

ज्ञाता ज्ञानं तथा ज्ञेयं द्रष्टा दर्शन दृश्यभूः ।

कर्ता हेतुः क्रिया यस्मात् तस्मै ज्ञप्त्यात्मने नमः ॥२॥

स्फुरन्ति सीकरा यस्मादानन्दस्याम्बरेऽवनौ ।

सर्वेषां जीवनं तस्मै ब्रह्मानन्दात्मने नमः ॥३॥

Yatah sarvani bhutani pratibhanti sthitani cha

Yatraivo'pasamam yanti tasmai satyatmane namah (1)

Jnata jnanam tatha jneyam drashta

darsana-drsyabhuh

Karta hetuh kriya yasmat tasmai jnaptyatmane namah (2)

Sphuranti sikara yasmad-anandasya'mbare'vanau

Sarvesham jivanam tasmai brahmanandatmane namah (3)

1. Salutations to that Reality in which all the elements and all the animate and inanimate beings shine as if they have an independent existence, and in which they exist for a time and into which they merge.

2. Salutations to that Consciousness which is the source of the apparently distinct threefold divisions of knower, knowledge and known, seer, sight and seen, doer, doing and deed.

3. Salutations to that Bliss Absolute (the ocean of Bliss) which is the life of all beings, whose happiness and unfoldment is derived from the shower of spray from that Ocean of Bliss.

VIVEKACHUDAMANI 465-471

(Sri Sankaracharya)

परिपूर्णमनाद्यन्तमप्रमेयमविक्रियम् ।

एकमेवाद्वयं ब्रह्म नेह नानास्ति किञ्चन ॥४६५ ॥

सद्घनं चिद्घनं नित्यमानन्दघनमक्रियम्।

एकमेवाद्वयं ब्रह्म नेह नानास्ति किञ्चन ॥ ४६६ ॥

प्रत्यगेकरसं पूर्णमनन्तं सर्वतोमुखम्।

एकमेवाद्वयं ब्रह्म नेह नानास्ति किञ्चन ॥४६७॥

अहेयमनुपादेयमनादेयमनाश्रयम्

एकमेवाद्वयं ब्रह्म नेह नानास्ति किञ्चन ।। ४६८ ।।

निर्गुणं निष्कलं सूक्ष्मं निर्विकल्पं निरञ्जनम्।

एकमेवाद्वयं ब्रह्म नेह नानास्ति किञ्चन ॥ ४६९ ।।

अनिरूप्यस्वरूपं यन्मनोवाचामगोचरम्।

एकमेवाद्वयं ब्रह्म नेह नानास्ति किञ्चन ॥ ४७० ।।

सत्समृद्धं स्वतः सिद्धं शुद्धं बुद्धमनीदृशम्।

एकमेवाद्वयं ब्रह्म नेह नानास्ति किञ्चन ॥४७१॥

Paripurnam-anadyantam-aprameyam-avikriyam

Ekameva 'dvayam brahma neha nana'sti kinchana. (465)

Sadghanam chidghanam nityam-anandaghanam-akriyam

Ekamevadvayam brahma neha nana'sti kinchana. (466)

Pratyag-ekarasam purnam-anantam sarvatomukhamaail

Ekameva dvayam brahma neha nana'sti kinchana. (467)

Aheyam-anupadeyam anadeyam-anasrayam

Ekameva'dvayam brahma neha nana'sti kinchana. (468)

Nirgunam nishkalam sukshmam nirvikalpam niranjanam

Ekameva'dvayam brahma neha nana'sti kinchana. (469)

Anirupya-svarupam yan-mano-vacham agocharam

Ekameva'dvayam brahma neha nana'sti kinchana.(470)

Satsamrddham svatah siddham suddham buddham-anidrsam

Ekameva' dvayam brahma neha nana'sti kinchana. (471)

465) The ever full, without beginning and end, inscrutable, and changless is Brahman the supreme who is one only and non-dual and in whom there is not even a trace of duality.

466) A mass (as it were) of Existence- Knowledge- Bliss Absolute, eternal, and devoid of any action is Brahman, the supreme who is one only and non-dual and in whom there is not even a trace of duality.

467) The internal subjective essence, the infinite, endless and all pervasive is Brahman the Supreme who is one only and non-dual and in whom there is not even a trace of duality.

468) That which can be neither rejected nor accepted and which is supportless is Brahman the supreme who is one only and non-dual in whom there is not even a trace of duality.

469) Attributeless, partless, subtle, without any disturbance and taintless is Brahman the supreme who is one only and non-dual and in whom there is not even a trace of duality.

470) He whose real nature is incomprehensible and who is not perceivable by mind and speech is Brahman the supreme who is one only and non-dual and in whom there is not even a trace of duality.

471) Self-existing, self-evident, pure, intelligence absolute and unlike any finite object is Brahman the supreme who is one only and non-dual and in whom there is not even a trace of duality.

BRAHMA JNANAVALI MALA

(1, 2, 16-21)

सकृच्छ्रवणमात्रेण ब्रह्मज्ञानं यतो भवेत्।

ब्रह्मज्ञानावलीमाला सर्वषां मोक्षसिद्धये ॥ १ ॥

असङ्गोऽहमसङ्गोऽहमसङ्गोऽहं पुनः पुनः ।

सच्चिदानन्दरूपोऽहमहमेवाहमव्ययः ॥ २ ॥ )

तापत्रयविनिर्मुक्तो देहत्रयविलक्षणः ।

अवस्थत्रयसाक्ष्यस्मि चाहमेवाहमव्ययः ॥ १६ ॥

दृग्दृश्यौ द्वौ पदार्थौ स्तः परस्परविलक्षणौ।

दृग्ब्रह्म दृश्यं मायेति सर्ववेदान्तडिण्डिमः ॥१७॥

अहं साक्षीति यो विद्याद्विविच्यैवं पुनः पुनः ।

स एव मुक्तः सन् विद्वानिति वेदान्डिण्डिमः ॥ १८ ॥

घटकुड्यादिकं सर्वं मृत्तिकामात्रमेव च।

तद्वद्ब्रह्म जगत्सर्वमिति वेदान्तडिण्डिमः ॥१९॥

ब्रह्म सत्यं जगन्मिथ्या जीवो ब्रह्मैव नापरः

अनेन वेद्यं सच्छास्रमिति वेदान्तडिण्डिमः ॥२०॥

अन्तर्ज्योतिर्बहिर्ज्योतिः प्रत्यग्ज्योतिः परात्परः ।

ज्योतिर्ज्योतिः स्वयंज्योतिरात्मज्योतिः शिवोऽस्म्यहम् ॥ २१ ॥

Sakrt-sravana-matrena brahma-jnanam yato bhavet

Brahma-jnanavali-mala sarvesham moksha-siddhaye. (1)

Asango'ham asango'ham asango'ham punah punah

Sachchidananda-rupo 'ham ahameva'ham avyayah. (2)

Tapa-traya-vinirmukto deha-traya-vilakshanah

Avastha-traya-sakshyasmi cha'ahameva'ham-avyayah. (16)

Drg-drsyau dvau padarthau stah paraspara-vilakshanau

Drg brahma drsyam mayeti sarva-vedanta-dindimah. (17)

Aham sakshiti yo vidyad vivichyaivam punah punah

Sa eva muktah san vidvan-iti vedanta-dindimah. (18)

Ghata-kudyadikam sarvam mrttika-matram-eva cha

Tadvad-brahma jagat sarvam iti vedanta-dindimah. (19)

Brahma satyam jagan-mithya jivo brahmai'va naparah

Anena vedyam sacchastram iti vedanta-dindimah. (20)

Antar-jyotir bahir-jyotih pratyag-jyotih parat-parah

Jyotir-jyotih svayam-jyotir-atma-jyotih sivo'smyaham. (21)

1) Here is a series of attributes of Brahman by hearing which even once, all would get liberation.

2) I am unattached, I am unattached, I am unattached again and again I say. I am of the form of Existence Knowledge-Bliss-Absolute alone. I am what I am. I am immutable indeed.

16) I am free from the three kinds of suffering (the Adhyatmika, Adhibhautika and Adhidaivika). I am different from the three bodies (gross, subtle, and causal). I am the witness of the three states (waking, dream and deep sleep). I am what I am. I am immutable indeed.

17) There are two things, viz., the Seer and the seen, which are different from one another; of these the Seer is Brahman, the supreme and the seen is Maya, unreal superimposition-thus proclaims Vedanta.

по 18) Only he who reflects and enquires about the Truth again and again and thereby knows that the 'I' is the witness, is wise and becomes liberated-thus proclaims Vedanta.

19) Even as an earthen jar, a wall, and all such things are earth alone, the whole of creation is Brahman, the supreme alone-thus proclaims Vedanta.

20) That which is to be known from all the scriptures is that Brahman alone is the Truth, the whole universe is false appearance and the individual being is Brahman alone and nothing else-thus proclaims Vedanta.

21) I am Siva, the internal light as also the external light, the universal spirit in all beings, who transcends the unmanifest Isvara, who is the light of all lights and who is self-illuminating and the light of the Self.

SRIMAD BHAGAVATAM

(I-i-1)

जन्माद्यस्य यतोऽन्वयादितरतश्चर्थेष्वभिज्ञः स्वराट्

तेने ब्रह्म हृदा य आदिकवये मुह्यन्ति यत्सूरयः ।

तेजोवारिमृदां यथा विनिमयो यत्र त्रिसर्गोऽमृषा

धाम्ना स्वेन सदा निरस्तकुहकं सत्यं परं धीमहि ॥

Janmady asya yato 'nvayad-itaratas-cha'rtheshvar abhijnah svarat

tene brahma hrda ya adikavaye muhyanti yat surayah

Tejo-vari-mrdam yatha vinimayo yatra trisargo'mrsha

dhamna svena sada nirasta-kuhakam

satyam param dhimahi

We meditate on that transcendent reality from whom the universe springs up, in whom it abides and into whom it returns, because he is invariably present in all existing things and distinct from all non-entities. We meditate on him who is self-conscious and self-effulgent, who revealed to Brahma by his mere will the veda that causes bewilderment even to the greatest sages, on account of whom the creation shines as a reality and who excludes illusion by his own self-effulgent glory.

(II-ix-32 to 35)

अहमेवासमेवाग्रे नान्यद्यत् सदसत्परम्।

पश्चादहं यदेतच्च योऽवशिष्येत सोऽस्म्यहम् ॥ ३२ ॥

ऋतेऽर्थं यत्प्रतीयेत न प्रतीयेत चात्मनि ।

तद्विद्यादात्मनो मायां यथाऽऽभासो यथा तमः ॥ ३३ ॥

यथा महान्ति भूतानि भूतेषूच्चावचेष्वनु ।

प्रविष्टान्यप्रविष्टानि तथा तेषु न तेष्वहम् ॥ ३४ ॥

एतावदेव जिज्ञास्यं तत्त्वजिज्ञासुनाऽऽत्मनः ।

अन्वयव्यतिरेकाभ्यां यत् स्यात् सर्वत्र सर्वदा ।। ३५ ।।

Aham eva 'sam eva'gre na'nyad yat sad-asat-param

Paschad aham yad etachcha yo'vasishyeta so'smy aham (32)

Rte 'rtham yat pratiyeta na pratiyeta cha'tmani

Tad vidyad atmano mayam yatha'bhaso yatha tamah (33)

Yatha mahanti bhutani bhutesu'chcha'vacheshv anu

Pravishtany apravishtani tatha teshu na teshv aham (34)

Etavad eva jijnasyam tattva-jijnasuna 'tmanah

Anvaya-vyatirekabhyam yat syat sarvatra sarvada (35)

Verily, in the beginning I alone existed; naught else existed-neither existence nor non-existence in the relative sense. Afterwards, too, I exist as all this and all that remains after all this has been created. The power that causes the perception in my being of objects which do not exist in reality, is my own maya or illusory power. It functions like a reflection, or like smoke veiling its own source (fire). Even as one may say that the gross elements enter or do not enter the bodies of living beings, depending upon the sense in which it is said, one may say that I have entered the bodies of living beings as the indwelling spirit or that I have not so entered, on account of my being infinite. The real seeker after truth should constantly seek the truth by the negative (not this, not this) method and the affirmative method (All indeed is Brahman).

(XII-xiii-23)

नाम सङ्कीर्तनं यस्य सर्वपापप्रणाशनम्।

प्रणामो दुःखशमनस्तं नमामि हरिं परम् ॥

Nama-sankirtanam yasya sarva-papa- pranasanam,

Pranamo dhukha-samanas tam namami harim param

Salutations to Hari, chanting whose names frees one from all sins and sorrow.

GOD IS ONE

(Swami Udayanacharya)

यं शैवाः समुपासते शिव इति ब्रह्मेति वेदान्तिनो

बौद्धा बुद्ध इति प्रमाणपटवः कर्तेति नैयायिकाः

( अर्हन्नित्यथ जैनशासनरताः कर्मेति मीमांसकाः

(क्रैस्तवाः क्रिस्तुरिति क्रियापररता अल्लेति महम्मदाः)

सोऽयं वो विदधातु वाञ्छितफलं त्रैलोक्यनाथो हरिः ।।

Yam saivah samupasate siva iti brahmeti vedantino

Buddha Bauddha iti pramanapatavah karteti naiyayikah

Arhannity atha jaina-sasana-ratah karmeti mimamsakah

(Kraistavah kristur-iti kriyapara-rata alleti mahammadah)

So'yam vo vidadhatu vanchhita-phalam

trailokya-natho harih.

He whom the Saivites worship as Lord Siva, the Vedantins as Brahman, the Buddhists as Buddha, the Naiyayikas well versed in the science of logic as Karta (the agent of action), the Jains as Arhat, the ritualists as Karma (the Christians engaged in action as Christ, the Muslims as Allah)-may that Lord Hari, the Lord of the three worlds fulfill all our desires.

AVOID WORRY

(Panchadasi-vii-168)

(Swami Vidyaranya)

यदभावि न तद्भावि भाविचेन्न तदन्यथा ।

इति चिन्ताविषघ्नोऽयम् बोधो भ्रमनिवर्तकः ।।

Yad abhavi na tad bhavi bhavi chenna tad anyatha

Iti chinta-vishaghno'yam bodho bhrama-nivartakah.

That which is not to happen will never happen; that which is to happen will certainly happen exactly as it should happen; this delusion-destroying knowledge does away with the poison of worry and anxiety.

ISAVASYA UPANISHAD-I

ॐ ईशावास्यमिदं सर्वं यत्किञ्च जगत्यां जगत्।

तेन त्यक्तेन भुञ्जीथा मा गृधः कस्यस्विद्धनम् ॥

Om Isa vasyam idam Sarvam yatkincha jagatyam jagat

Tena tyaktena bhunjitha ma grdhah kasya-svid dhanam.

All this-whatsoever moves in this universe-should be covered by the Lord. Protect (your self) through that renunciation. Do not covet any one's wealth for whose is wealth?

GOD AND WORLD-NOT DIFFERENT

(Swami Dayananda Saraswati)

हरिरेव जगत् जगदेव हरिः हरितो जगतो न हि भिन्नतनू ।

इति यस्य मतिः परमार्थगतिः स नरो भवसागरमुत्तरति ॥

Harir-eva jagat-jagadeva harih Harito jagato na hi bhinna tanu

Iti yasya matih paramartha-gatih sa naro Bhava-sagarm-uttarati.

Lord Hari (the all-pervasive Supreme Lord) is verily the world; the world is certainly Lord Hri and ther is not even the least difference between the two; he who understands and realises this truth is saved from the ocean of Samsara, the mundane life of birth and death.

THREE SINS TO BE TRANSCENDED

(Avadhuta Gita-viii-l)

त्वद्यात्रया व्यापकता हता ते ध्यानेन चेतःपरता हता ते।

स्तुत्या मया वाक्परता हता ते क्षमस्व नित्यं त्रिविधापराधान् ॥

Tvad-yatraya vyapakata hata te dhyanena chetah-parata hata te;

Stutya maya vak-parata hata te Kshamasva nityam trividha'paradhan.

This verse entreats pardon from the Lord for three "sins" committed daily by the devotees and aspirants. What are they? They are: (1) through pilgrimage one rides rough-shod over the all-pervasive and beyond-space- nature of the supreme; (2) through meditation one sets at naught the great Vedic declaration that the Atman-Brahman is beyond the reach of the mind and (3) through verses of praise one, without any consideration, flouts the transcendental nature of the Absolute which is beyond all speech. This verse reveals the great truth that Lord transcends space and time, thought and speech.

GOD IS EVERYTHING

(Svetasvatara Upanishad-IV-3)

त्वं स्त्री त्वं पुमानसि त्वं कुमार उत वा कुमारी।

त्वं जीर्णो दण्डेन वञ्चसि त्वं जातो भवसि विश्वतोमुखः ॥

Tvam stri tvam puman asi tvam kumara uta va kumari

Tvam jirno dandena vanchasi tvam jato bhavasi visvatomukhah.

Thou art the woman, Thou art the man, Thou art the youth and also the maiden; Thou art the aged man who totters along leaning on the walking stick; Thou art born with faces turned in all directions.

Nasadiya Sukta

Hymn of Creation (Rigveda 10-129-1 to 7)

नासदासीन्नो सदासीत् तदानीं नासीद्रजो नो व्योमा परो यत् ।

किमावरीवः कुह कस्य शर्मन्नम्भः किमासी गहनं गभीरम् ॥१॥

Naasadaaseenno sadaaseet tadaaneem

naaseedrajo no vyomaa paro yat,

Kimaavareevah kuha kasya sarmannaabhbhah

kimaaseedgahanam gabheeram. (1)

1. Then (1) there was neither Being nor Non-being (2); there was neither the (physical) space (rajah) nor the Supreme Space (3). What was there as a cover and where(4)? Whose was the blessedness (sarman) (5)? Was there water, deep and unfathomable?

Nasadiya Sukta hymn, hymn of creation, is one of the most profoundly philosophical mystical and beautiful of Vedic hymns. Sayana in his commentary states that the hymn refers to the state of the universe during pralaya or cosmic dissolution. How then the seer of this Mantra who must have lived millions of years later know it? In the realm of the Absolute the past and the future are contained in the present. Creation is a timeless process. As Swami Vivekananda's experience contained in his 'Song on Samadhi' shows, in the superconscious state, as the soul rises through different levels of consciousness to the Absolute it encounters the stages of creation in the reverse order. In other words this Sukta is the expression of a profound mystical experience of the origin of creation. The seer of this wonderful hymn is unknown.

1. The first part of this line negates time and the second half negates space.

2. Chhandogya Upanishad 6-2-1 states that at the beginning there was only pure Being (sat) without a second. But Taittireya Up. 2-7-1 states that at the beginning there was only Non-being (asat), i.e., the unmanifested condition of Being. The present hymn negates both Being and Non-being because these are only relative terms. Some Western scholars see the rudiments of the Samkhya philosophy in this hymn and take sat as implying Purusha and asat as Prakriti.

3. Rajah is interpreted by Sayana as 'the world' and by Western scholars as 'air.'

4. There was no cover as there was nothing to be covered.

5. There was no enjoyer (bhokta) as the ego has not got differentiated. Sarman is interpreted by Sayana as 'enjoyment or fruition of pain and pleasure,' and by Western scholars as shelter protection, support, etc.

न मृत्युरासीदमृतं न तर्हि न रात्र्या अह्न आसीत् प्रकेतः ।

आनीदवातं स्वधया तदेकं तस्माद्धान्यन्न परः किं चनास ॥२॥

Na mruturaa seedmrutam na tarhi

na raatrayaa ahana aaseet praketah,

Aaneedavaatam svadhyaa tadekam

tasmaaddhaanyanna parah kim canaasam. (2)

2. Then (1) there was neither death immortality(2); nor any sign of day and night. That one (3), breathless, breathed (4) by its own power (5). Other than that there was nothing beyond.

In this hymn the seer is trying to express his ineffable experience of the Absolute through the negation of a series of antinomical concepts. The intended effect of this mode of expression is, like that of the koan of Zen, to break the conceptualisation process and lift the consciousness to a plane of unitary vision. It is perhaps a mistake to interpret this ancient hymn in terms of later philosophical concepts like Brahman, Maya, etc. It is best understood by meditating upon it.

1. The timeless period before creation.

2. Death takes place only in the manifested world or Virat; beyond that lies the world of Hiranyagarbha where only remains immortal. But the Absolute transcends even these states of human existence. Cf. yasya chbyamritam yasya mrityuh (Rigveda 10-121-2).

3. A significant phrase which refutes the Samkhya dualism of Prakriti and Purusha.

4. Asad shows no signs of life like respiration metabolism, etc.; nevertheless it is alive. Likewise in the primordial state Reality is life but without any signs of life-activity.

5. Sayana interprets svadhaya as 'by Maya' (svasmin dhiyate dhriyate asritya vartate iti svadha maya). The Tantric concept of chit-sakti and the Upanishadic concept of Prana may also be traced here. Cf. devatmasaktim svagunairnigudham of Sv. Up. 1-3.

तम आसीत् तमसा गूळ्हमग्रेऽप्रकेतं सलिलं सर्वमा इदम ।

तुच्छयेनाभ्वपिहितं यदासीत् तपसस्तन्महिनाजायतैकम्॥३॥

Tama aaseet tamasaa goolhamagre

apreketam salilam sarvamaa edam,

Tuchye naabhvapihitam yadaaseet

tapasastanmahinaa jaaya taikam. (3)

3. In the beginning (1) there was darkness (2) concealed (3) in darkness; all this (4) was indistinguishable (5) water (6). That which was the all- encompassing (7) one covered by the void (8), manifested itself (9) by the greatness of Tapas (10).

1. That is, before the creation of the world.

2. It cannot be denied that the word darkness (tamas) here anticipates Sankara's concept of Maya or Ajnana.

3. From the root 'guh, 'to hide. As Sayana has pointed out, the expression clearly indicates that Ajnana is not mere absence of knowledge but 'something positive' (bhava rupam).

4. All this manifested world.

5. Apraketam-without a mark.

6. Salilam, i.e., salilam iva, like water, i.e., the primordial cause.

7. So says Sayana. Macdonell takes 'abhu' to mean 'coming into being' (similar ababhuva of verses 6 and 7).

8. Tucchya is the Vedic form of tuccha meaning void, insignificant. It also means chaff. Just as the chaff encloses the grain so Maya enveloped the emerging reality of the world.

9. Ajayata was born, does not mean the creation of something new; rather it means the manifestation of something already present in a potential form.

10. Tapas means any concentrated effort. Here, according to Sayana, God's precognition or prevision of things to be created. Cf. yasya jnanamayam tapah (Mun. Up. 1-1-9). The infinite formless Reality preparing itself to assume form, the focussing of divine will-this is what tapas really means here.

कामस्तदग्रे समवर्तताधि मनसो रेतः प्रथमं यदासीत् ।

सतो बन्धुमसति निरविन्दन् हृदि प्रतिष्या कवयो मनीषा ॥४ ॥

Kaamastadagre samavartataadhi

manaso retah prathamam yadaaseet,

Sato bandhumasati niravindan

hrudi pratishyaa kavayo maneeshaa. (4)

4. In the beginning (1) there arose desire (kama) (2) which was the first seed (retas) of mind (3). Sages seeking (pratishya) in their hearts through intuition (manisha) (4) discovered the connection (bandhu) of the Sat in the Asat (5).

1. In the previous stanza it was mentioned how, by the power of God's Tapas, Being started manifesting itself out of the Unmanifested at the time of creation. This is referred to here.

2. The desire to create the universe arose in the Supreme Self. Creation in Indian thought means the re-production or projection of last kalpa's existence which had remained dormant during the great dissolution (Pralaya).

3. Desire (kama) is the seed of the mind. If all desires are destroyed, the mind would cease to exist. Sayana however separates 'desire' from 'seed of mind' and takes mind in the plural. According to him the whole line means: "When the seeds of karma of all living beings of the previous kalpa ripened in their minds which were lying latent in the Unmanifested, the desire to create the universe arose in the Supreme Lord who is the giver of the fruits of action." So he takes retas as the seed of karma. 'Seed of mind' belongs to living beings where 'desire' belongs to God.

4. Seeking here means seeking through meditation.

For Manisha, see Kath. Up. 6-9 and Ai. Up. 5-2.

5. Prof. Kunhen Raja who sees the origins of Samkhya philosophy in this hymn says: "It is said that in the beginning there was darkness encompassed by darkness. That is the Tamo Guna or the material aspect of the basic fundamental of the universe. Then there is the life, which is called the breathing without breath (anidavatam), the power within. That is Sattva Guna or Light or Sentient aspect. Then the Tapas is the Rajo Guna, the activity. On account of these aspects, there was the Will (kama) which corresponds to the Buddhi. This primal feature is the seed for the activity of what is known as the Antah-karana, that is the Manas." (Poet Philosophers of Rig Veda, p. 227).

तिरश्चीनो विततो रश्मिरेषामधः स्विदासी३दुपरि स्विदासी३त् ।

रेतोधा आसन् महिमान आसन्त्स्वधा अवस्तात्

प्रयतिः परस्तात् ॥५॥

Tirascheeno vitato rashmireshaamadhah

svidaasee dupari svidaaseet,

Retodhaa aasan mahimaana aasantsvadhaa

avastaat prayatih parastaat. (5)

[The meaning of this fifth stanza is obscure and the translation given here is based on several collated interpretations.]

5. The rays of these (1) spread out (vitatah) across (tirascinah) above and below (2). There were bearers of seed (retodha) and great things (mahimanah) (3), there was power (svadha) below and impulse (prayatih) above (4).

1. 'Esham of these,' evidently refers to something in the previous stanza, but what it is, is not clear. Griffith suggests that an intervening stanza may, perhaps, have been lost. According to Sayana 'these' refers to the created worlds.' 'Rays' he interprets as 'like rays.' Macdonell believes 'rasmih' means 'cord,' the 'bandhu' mentioned in the previous stanza and he quotes Rigveda 7-25-18 in support of this.

2. According to Sayana, creation was so sudden like a flash of lightning that though the worlds were actually created one after another (as mentioned in the Tai. Up. 2-1-1) they spread out rapidly like a ray of light and it was therefore difficult to say which one was above and which one below.

3. According to Sayana, 'retah-adhah' 'bearer of seed' means living beings, the enjoyer (bhokta), and 'mahimanah' the non-living objects meant to be enjoyed (bhogya). Macdonell thinks 'retodha' (impregnators) and Mahimanah (powers) refer to male and female cosmogonic principles.

4. Sayana interprets 'svadha' as 'food' and 'prayatih' as 'the eater of food,' the total meaning being 'the objective world was created after the subjective world,'

Sayana's interpretation of the stanza, based on later Vedantic thought, is clear but unconvincing, whereas the interpretation offered by Macdonell, Griffith and other Western scholars can only be described as ignotum per ignotius.

को अद्धा वेद क इह प्र वोचत् कुत आजाता कुत इयं विसृष्टिः ।

अर्वाग्देवा अस्य विसर्जनेनाऽथा को वेद यत आबभूव ॥ ६ ॥

Ko addhaa veda ka eha pravocat kuta

aajaataa kuta eyam visrushtih,

Arvaagdevaa asya visarjanenaa athaa

onko veda yata aababhoova. (6)

इयं विसृष्टिर्यत आबभूव यदि वा दधे यदि वा न ।

यो अस्याध्यक्षः परमे व्योमन्त्सो अङ्ग वैद यदि वा न वेद ॥ ७ ॥

Eyam visrushtiryata aababhoova

yadi va dadhe yadi vaa na,

Yo asyaadyakshah parame vyomantso

anga vaida yadi vaa na veda. (7)

6. Who really knows? Who can tell, whence this originated and whence (1) this creation? The gods came after this creation (2); therefore who knows whence it arose.

7. That from which this creation arose - does it support it or does not (3)? He who is the superintendent (4) in the highest heaven, He certainly knows or perhaps he knows net (5).

1. According to Sayana, the first 'whence' refers to upadana karana, material cause, and the second 'whence' refers to nimitta karana, instrumental (or personal) cause.

2. According to one school of thought all gods are only parts of the Virat, the manifested universe.

The gods referred to here are the presiding deities of different organs, celestial spheres, etc., and not the Supreme Deity.

3. The question is whether the created universe got separated from the creator (as an egg from a hen) or whether God remained immanent in creation. It is answered in the famous passage 'tat srshtva tadevanupravisat' in the Tai. Up. 2-6-1.

4. Adhyaksha, the overseer, the eternal witness.

5. He knows not because He is knowledge itself. Knowing implies objectification, but there is nothing apart from God and so He cannot be said to 'know' in the ordinary sense. Sayana's interpretation is: "If He does not know nobody else does." Some scholars see in these lines signs of atheism and the germs of Samkhya philosophy but this is an unwarranted assumption which Sayana himself repudiates.

NASADIYA SUKTAM

(H.H. Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj)

Then there was no non-existence nor existence. There was no earth, there was no sky. What was there? It was a vast expanse of deep waters profound and tremendous. There was no death, there was no immortality. There was no night and there was no day. That alone was there breathing within itself. Nothing there was outside It or external to It.

(ne It was all a kind of darkness, as it were, enveloping everything at that time-all waters of cosmic universality. There was intense Tapas and high concentration of Consciousness at that time. In that, arose the central desire of the Cosmic Being, the origin of what we call mind, the thinking principle. The great sages discovered in this condition, existence which is commensurate with this condition of non-existence. It was the heart of all beings. It was radiating light from all sides. It was indeed darkness due to excess of light, because there was no one to behold that light.

No one can know how this creation came, because even the gods came after creation. Who can know then, the origin of creation? Oh! What a wonder! How did this world come at all? How this creation? Only the One who created this universe will know how it came. Perhaps, He, too, does not know.

Harih Om Tat Sat

SANTI MANTRA

Brhadaranyaka Upanishad-V-I

ॐ पूर्णमदः पूर्णमिदं पूर्णात् पूर्णमुदच्यते ।

पूर्णस्य पूर्णमादाय पूर्णमेवावशिष्यते ॥

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः॥

Om Purnam-adah punrnam-idam purnat purnam-udachyate,

Purnasya purnam-adaya purnam-eva'vasishyate.

Om Santih! Santih! Santih!

Om. That (supreme Brahman) is infinite, and this (conditioned Brahman) is infinite. The infinite (conditioned Brahman) proceeds from the infinite (supreme Brahman). then through knowledge), taking the infinite (conditioned Brahman) from the infinite (supreme Brahman). It remains as the infinite (supreme Brahman) alone. Om! Peace! Peace! Peace!

HARI OM TAT SAT

H.H. SRI SWAMI BRAHMANANDAJI MAHARAJ

(A Life-Sketch)

"That rare person who attains success in meditation is really a blessed one. None can describe his nature fully. People who try to describe a sage can be broadly brought under three groups. Many describe his body and its activities. They speak about his parents, his birth, his childhood, his school education, and so on. Some others describe the sage's charitable nature, his love towards others, his instructions to his disciples, his equal vision, etc. Only very few, maybe one in a million, describe the sage rightly through statements like 'I am He' and 'He is l'. Only those who have themselves realized the Truth can boldly assert their identity with the sage, because they have directly experienced the truth of the Vedic declarations neti, neti (not this, not this) and sarvam khalvidam brahma (All this is verily non-dual Consciousness, pure and infinite). That the first two groups of people who think that they are giving beautiful, long and eloquent descriptions of the sage are far from right, needs no special mention."* Nevertheless, we who belong to the first two groups cannot do otherwise than make the traditional attempt to recount the life story of a great soul, who was our teacher.

Thiruchendur in Tamil Nadu has one of the six famous temples of Lord Subrahmanya. A community of dedicated devotees of the Lord live there. One such

*Supreme Knowledge-2nd Edition Page No. 356 H.H. Sri swami Brahmanandaji Maharaj.

Brahmin family migrated a few generations back to Tiruvanantapuram, Kerala State. On 26th June, 1910, Revered Swami Brahmananda Maharaj was born into that family, to the pious parents Sri Krishna lyer and Srimati Rukmini Ammal, in the village Thonnakkal, near Tiruvanantapuram (Trivandrum). He was the eldest of five children. His parents named him Nilakantan.

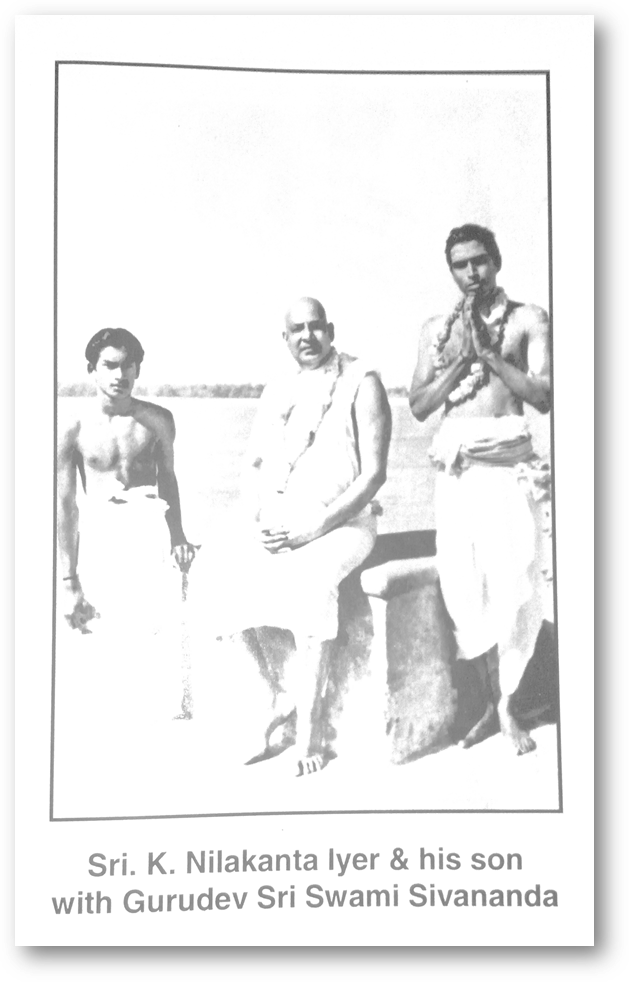

His studies commenced in Tiruvanantapuram. After graduating from Travancore University (now Kerala University), he joined the services of the then princely state of Travancore. He was married and in the year 1932, a son was born, who was named Sundarakrishnan. Twelve years later, in 1944, his wife passed away and Nilakanta lyer assumed full responsibility for the upbringing of the boy. Though pressed by his parents to remarry, he steadfastly declined. The premature death of his wife appears to have wrought some changes in his life for, around this time, he went on a pilgrimage to Ramanashram in Tiruvannamalai where he was blessed with the darshan of the great sage of Arunachala, Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi. He spent a day in the Ashram.

Shortly after this, sometime in 1946, he happened to be browsing through the bookstall in Tiruvanantapuram Railway Station, where he happened upon the newly published Practice of Yoga-Volume I by H. H. Gurudev Sri Swami Sivananda Maharaj. So inspired was he by the book and the author that, during the same year, he journeyed to the foothills of the distant Himalayas for darshan of the Holy Master. Gurudev blessed him with Mantra Diksha during that visit. From that time onwards, he visited the Ashram once every year, with the exception of 1950 when Gurudev made his All-India Tour.

In 1947, he sought Gurudev's permission to join the Ashram and give up hearth and home. At that time, his son was only fifteen years. Gurudev made some inquiries and asked him how much longer he would have to continue in service so as to be eligible for pension benefits. Nilakanta lyer replied, "ten years more". Then Gurudev advised him to continue in service until the time when pension eligibility was secured. Never, at that time, could Nilakanta lyer have imagined that his pension benefits would hold him in good stead after retirement for almost fifty years!

So, inspired was he by Gurudev Sri Swami Sivananda Maharaj and his divine mission that as early as 1947 Nilakanta lyer organised a branch of the Divine Life Society, in his own home in Tiruvanantapuram. Inauguration ceremonies were conducted on January 26, 1947, with Revered Sri Swami Tapasyanandaji Maharaj of the Ramakrishna Mission officiating. Nilakanta lyer served as Secretary. In addition to the bi-weekly meetings, all special holy days as well as, Sivananda Ashram special anniversaries were celebrated with much sincerity and devotion. Gurudev's Diamond Jubilee in 1947, was honoured by a grand two-day celebration and a crowded program of puja, of puja, akhanda mahajapa, inauguration of yoga classes, mantra writings, public meetings and prayers for the long life of Sri Swamiji Maharaj. Periodically, the branch printed small tracts containing Gurudev's teachings and sent them to the Ashram for distribution as jnana prasad. The branch library was also located in his home and served as a distribution point for Gurudev's books and teachings.

In 1950, Gurudev set out on his All-India and Ceylon Tour. Nilakanta lyer was appointed to organise Gurudev's programme in the Tiruvanantapuram circle. His father, also, was a member of the Tour Organising Committee. Gurudev blessed their home with his sublime presence and performed arati in their puja room to the great satisfaction of the entire family.

In 1951, Nilakanta lyer along with his son, Sundarakrishnan, and one or two friends set out on a pilgrimage with the intention of visiting the famous temples in the South as well as in North India. Their yatra in the South completed, they arrived at the Ashram with plans to set out for the holy mountain shrines of Kedarnath and Badrinath after a few days. For the son, who was not yet twenty years old, this was his first visit to Sivananda Ashram. As a modern young scholar, he was having some doubts concerning the efficacy and value of the spiritual life and, with only a half-hearted interest, he made salutations to Revered Gurudev. After visiting the Ashram for a few days, they commenced their journey accompanied by one Swami Sadananda and two other persons, who were residents of the Ashram. Thus, a group of five persons started their pilgrimage to Kedarnath.

While the group was returning from Kedarnath by foot, Sundarakrishnan happened to step on a sharp thorn which lodged itself in his left heal. Within a day or two, walking became very troublesome for him. At times, he covered the distance atop a pony. Nevertheless, by the time the group reached Srinagar on their way to Badrinath, his condition had become serious. Nilakanta lyer consulted a doctor there for treatment, but the doctor found the wound very seriously infected and advised them to return to Sivananda Ashram Hospital in Rishikesh and take treatment from Dr. Rai immediately. Requesting the rest of the group to complete their Badrinath Yatra, father and son returned to the Ashram.

In the Ashram Hospital, the wound was treated, but the heel turned black, discharging fluids and causing excruciating pain. During the dressing of the wound, the boy cried aloud because of the severe pain. This drew Gurudev's attention. Gurudev came to see the boy and instructed the medical assistants to do the dressing gently. As the condition of the leg deteriorated further, the doctors decided to perform amputation of the foot in a hospital in Dehra Dun and scheduled the surgery to occur after two days. But on the second day, the doctor noticed what appeared to be a miraculous improvement and announced, to the immense joy of all, that amputation would not be necessary because somehow the wound was almost 90% healed! "What could have happened?" Nilakanta lyer asked his son.

Only then did the boy narrate the whole story. Two days before during his regular afternoon visits to the various departments of the Ashram, Gurudev Sri Swami Sivananda had come to his room at about 1:30 p.m. accompanied by Swami Venkatesananda and a few other Ashram swamis,. Gurudev asked Sundarakrishnan to remove the bandage. Then Gurudev chanted thrice the Mrityunjaya Mantra, followed by a triple recitation of the Mahamantra (Hare Rama Hare Rama...). Then, in a very loud voice, the Holy Master intoned 'OM' thrice. The boy was told to replace the bandage, and Gurudev departed. When Nilakanta lyer heard this, he told his son in a serious tone about the procedure the doctors had been planning and that it was due to the grace of Gurudev only that the wound had begun to heal. Earlier, the boy did not have faith and regard for Gurudev, and Nilakanta lyer pointed out this defect.

For about a month, they continued their stay in the Ashram until the boy was able to walk normally. When the day came for their departure to Tiruvanantapuram, both father and son went for Gurudev's darshan and blessing. With full faith and love and gratitude, the boy fell at the feet of Gurudev in full prostration. Gurudev took this occasion to impart final instructions to the boy. Gurudev told him that, after some years had passed, his father wanted to come and join the Ashram, and that the boy should not raise any objections. Rather, the boy should happily and willingly allow the father to depart in peace.

Over the next six years, Nilakanta lyer continued to visit the Ashram annually. During one of these visits, Gurudev Sri Swami Sivananda bestowed upon him the gerua cloth, insignia of the holy order of Sannyasa, as well as the sacred Sannyasa Mantras. He even bestowed upon him the monastic name Swami Brahmananda Saraswati. But as he was still in government service and involved in family obligations, the viraja homa (sacred fire ceremony) was not performed at that time. Gurudev advised him to make special study of the Upanishads and, as final instructions, proclaimed: "Brahmananda Swami, live here! Where else can you find the holy Himalaya and Ganga!"

As advised by Gurudev, Nilakanta lyer remained in government service until 1957. On October 10, 1957, he took voluntary retirement from service. At that time, he was serving as a Class-1 Officer (a high rank), as Superintendent of the Kerala Government Press, Tiruvanantapuram. Forty years later, when asked by a student, what had been his work prior to Sannyasa, Swamiji replied simply, "a clerk in a government press"

and changed the subject. To his students and colleagues, barely anything was known about his early life.

When his son was married in 1958, Nilakanta lyer shifted to Rishikesh. Being the eldest son, he still had to discharge some duties towards his parents and also had some responsibilities remaining concerning his only son. So, he divided his time between Rishikesh and Tiruvanantapuram. He used to spend eight or nine months in Rishikesh and three or four months in Tiruvanantapuram. During the early years of his life at Rishikesh, he lived at Ramnagar. Later he shifted to Muni-ki-reti along with some fellow disciples and lived in a thatched hut in the Ram Ashram premises. He also stayed for a while near the Ashram at Hanuman Mandir on the banks of the Ganga. During this period (1958-1963), Nilakanta lyer offered some seva in various departments of the Ashram.

In those days, sometimes, Gurudev used to send biscuit packets to the sadhaks who were serving in various departments. On one occasion, after receiving biscuit packets, Nilakanta lyer and some other inmates went to Gurudev to explain that they were concerned that the cost of the packets was too much for the Ashram to bear as the Ashram was facing serious financial constraints at that time. Gurudev replied, "I know everything. You don't worry about this!" Such was the love and compassion that Sri Gurudev had for the inmates and devotees.

Gurudev shed his mortal coil in July, 1963. At that time, Nilakanta lyer was in Tiruvanantapuram attending to his old father, who was sick and bed-ridden due to dislocation of the hip joints. Hearing the news on the radio, he started making preparations to leave for Rishikesh. But the family astrologer advised him to remain in Tiruvanantapuram itself, as the end of his own father was fast approaching. With a heavy heart, he remained there. As predicted, in August, 1963, his father passed away, and Nilakantan performed the last rites for his father according to custom.

Around this time, Sringeri Sankaracharya, H.H. Sri Abhinava Vidya Theertha visited Tiruvanantapuram. A sect of the local Brahmin community, including Nilakanta lyer, went for the darshan of His Holiness. The Acharyaji advised them to worship Lord Subrahmanya. During a subsequent discussion of this advice by the group, Nilakanta lyer suggested that the Acharya's injunction could be carried out best by building a temple for the Lord and doing regular worship there. This idea was readily accepted by the community and a committee was formed. Nilakanta lyer was entrusted by the entire community with the responsibility of constructing the temple as Convener. The temple was constructed in accordance with the Pancharatra Agama and the consecration ceremony was performed in June, 1964. A few weeks after this, Nilakanta lyer returned to Rishikesh.

After this, he made Occasional visits to Tiruvanantapuram for one particular reason: no child had been born to his son. Finally, in 1966, Nilakanta lyer consulted the family astrologer and accordingly arranged for the propitiating ceremony of some departed soul in their lineage. Then, in 1967, a female child was born. In 1968, Nilakanta lyer attended the first year birthday celebrations of his grandchild. Then, with a sense of completion of all his responsibilities towards earthly relations, Nilakanta lyer retired to Rishikesh permanently.

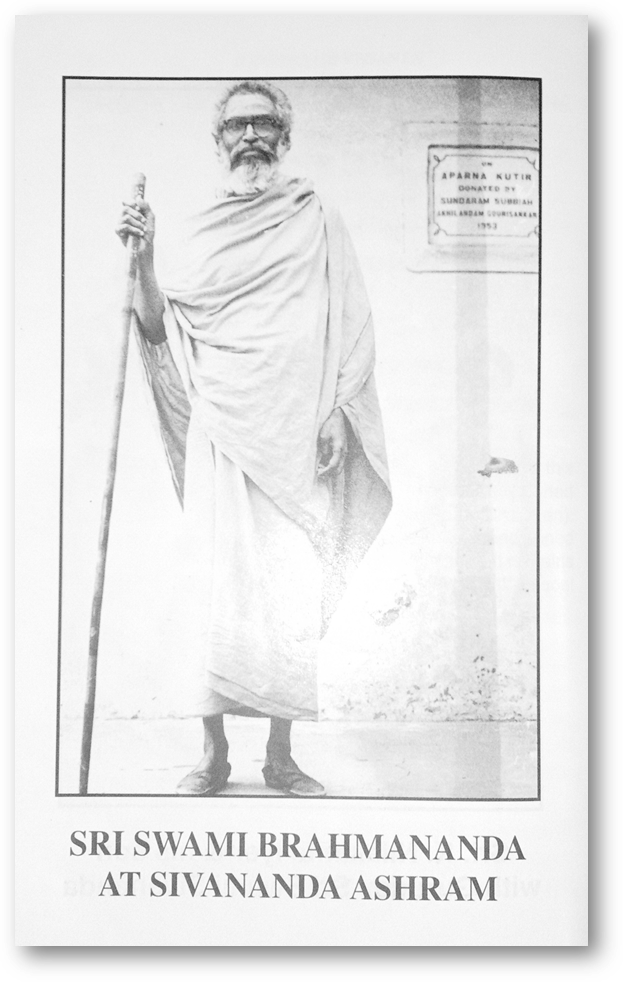

According to his horoscope, the year 1968 presaged a very critical period in which death from illness was a possibility. Not knowing what the future would hold in store, he became anxious to complete as quickly as possible the formal viraja homa ceremony that had not been performed, when he had received the Sannyasa Mantras, gerua cloth and monastic name from worshipful Sri Gurudev, Sri Swami Sivananda years earlier. Since H.H. Sri Swami Chidanandaji Maharaj, President of the Divine Life Society, was away on foreign tour, Nilakanta lyer approached the General Secretary, H. H. Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj and requested completion of the Sannyasa Disksha. Thus, on the Holy Guru Purnima Day in July, 1968, the holy viraja homa ceremony was performed and, assuming the monastic name given him by Gurudev, Swami Brahmananda Saraswati donned the gerua cloth and embraced the Holy Order of Sannyasa.

Prior to this time, he had been staying in a room in Hanuman Mandir just in front of the Ashram. After Sannyas, Swamiji shifted to room No. 23, Vaikuntha Dham in the Ashram, a room he was to occupy for the next 30 years! In such high regard did Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj hold Swami Brahmananda that, after the Sannyasa ceremony, he offered Swami Brahmananda a desk in his own office, and requested Swamiji to assist him in his office work. But Swami Brahmananda politely declined, humbly replying that he would prefer to do some seva while remaining in his own room.

Swamiji was a member of a study group in the Ashram which met daily, at fixed hours, and went through various scriptures. The members of this group knew Tamil, Malayalam, English, and some Sanskrit and Hindi. Scriptures like the Brahma Sutras, Upanishads, and Bhagavad Gita were studied by comparing the commentaries written in the various languages. The pace was quite unhurried and the grasp was thorough. It took one and half years to study the first six chapters of the Bhagavad Gita. After lunch, they would take a little rest and, around 1:00 p.m., they would commence the study. Even on occasions where rest was not possible, Swamiji's dedication, attendance, and punctuality was 100%. In addition to this, Swamiji attended the early morning prayer meeting of Swami Vidyananda for about ten years. The prayer session would commence at 3:30 a.m. with recitation of selected mantras from each Upanishad and also some chapters of the Bhagavad Gita accompanied by the melodious sounds of veena and tambura. In a week's time, they covered selections from all the twelve major Upanishads and the entire Bhagavad Gita.

Some time in the year 1978 or 1979, prompted by a neighbour, who was a resident sadhak, Swamiji started reading and discussing Vedantic text in his room with a few resident sadhaks. Gradually, this took the form of a class which was attended by a number of inmates, guests and visitors. Three regular classes were conducted: one in the morning, the second in the afternoon, and the third in the evening, each lasting for about forty-five minutes. For years and years, the classes were held in Swamiji's little room until the number of students swelled to overflowing, and then the classes were shifted to a nearby hall.

Swamiji covered all the traditional texts and included modern authors as well; the Upanishads, Bhagavad Gita, Ashtavakra Gita, Yoga Vasistha, Tripura Rahasya, Amritanubhava, Bhakti Sutras, Atma Bodha, Vivekachudamani, Pancadasi, Adhyatma Ramayana, Selections from the Bhagavatam and Ramayanam, Talks with Ramana Maharshi, Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, I am That by Nisargadatta Maharaj, Consciousness Speaks by Ramesh Balsekar, and Heart of a Gopi, to name just a few. The Yoga Vasistha was perhaps Swamiji's favourite text. Once Swamiji taught it four times continuously for about six years, reading the entire two volumes of Swami Venkatesananda's translation which is entitled "The Supreme Yoga", sentence by sentence.

In addition, Swamiji used to take Vedanta classes for the students of the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy and also gave special classes on Vedanta to groups of foreign visitors and guests, who frequented the Ashram. Except for short periods in 1984 and 1991, Swamiji conducted his formal classes regularly until December 1995. After that, due to weakened health, the formal classes were stopped. But the students kept coming and small, informal sessions continued to be held in Swamiji's room up to almost the very end of his life.

In his classes, Swamiji never lectured. His method was to read the text and explain whatever it was with the Vedantic touch. Differences in words and concepts never restrained him from pointing towards the 'Absolute'. Swamiji would unfold continuously and effortlessly 'That' which is beyond all words and thoughts. With absolute conviction and unending patience, he would urge his listeners to constantly and deeply reflect over their own daily experience of deep sleep, dream, and waking states.

"You must clearly know, who the 'I' in you is, that is the first step. You presume there is an 'I', and you think that 'I' is the body and mind, which it is not. If you go on thinking 'I am the body and the mind', none of these teachings will enter the heart, and there will be no progress on the spiritual path. You are not this body-mind. This body-mind exists only during the waking state. There are two other states of consciousness, which we experience everyday. In the dream state, you have another body and mind. And in the deep sleep state, you are without the body and mind. Why don't you pay attention to those two states? They constitute the major portion of your life, two-thirds of your life. If you take into consideration only one-third of life, only the waking state, how do you expect to solve the problems involving the whole of life? If you analyse the deep sleep state and the dream state, you will never say 'I am this body'. This body exists during only one of the three states. We are trying to know that 'I' which identifies itself with this body in the waking state, which identifies itself with another body in the dream state, and which has no body in the deep sleep state. This 'I', who had no body in the deep sleep state, dreamt as a butterfly in my dream and as a human being now. Which is the truth?"

Thus, Swamiji would drive home the 'truths' clearly, even to those sadhaks not having a Hindu religious background. He loved questions and always encouraged students to clear all doubts. His pet response to any overly-interrogative student was a beautiful smile and the advice, "Do you really want to know God? You must really want it. Argument has its limit. What is needed now is reflection, deep reflection. Reflect over it. Think about it. Bring to your mind, what the scriptures and the Masters are saying. So many pages are there, but what they say is really not very much; it is really very little. What is that 'very little', the essence of all this? You must come to your own conclusion. It must be your conclusion, not a piece of borrowed information from a book or from others. I Am that, I Am, that great declaration, "Aham Brahmasmi."

Bring that to the intellect or mind again and again. In the course of time, that thought itself will dissolve. It is a mystery. Try it. Have faith in the Masters and the scriptures. This is the ultimate sadhana." Over the decades, hundreds of students have benefited from these classes.

A beautiful tribute was written about Swamiji in the year 2000 by a devotee: "His Holiness Sri Swami Brahmananda Maharaj is a senior monk of the Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, whose towering spiritual insights have sparked the flame of aspiration in the hearts of countless students from around the world. Swami Brahmananda radiates a peace so palpable that, it touches a wellspring of joy in the hearts of sincere aspirants. Swami Brahmananda speaks from a depth of understanding which empowers his words to cut through the veil of ignorance. His wisdom, which is not from the intellect but from the very Source of Truth, is shared with tremendous patience and love."

Swamiji wrote articles for the 'Divine Life', the monthly journal of the Society, and at times did proofreading for the journal and important books of the press. His first work, The Philosophy of Sage Yajnavalkya, was serialised in the Divine Life magazine and later published in book form in the year 1972. The second book, Revelation of the Ever Revealed, (Sage Totakacharya's Sruti-sara-samuddharanam) was released in 1978. A booklet, Brahmasutras-A Remembrancer, was published in 1984. Then another booklet, Quintessence of Spiritual Practice (Acharya Sankara's Sadhana Pancakam), was printed. In addition to these works, Swamiji edited Gurudev Sri Swami Sivanandaji's Brihadaranyaka Upanishad from incomplete manuscripts. This was first published in the year 1985. Also, he edited some works by H.H. Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj and H.H. Sri Swami Chidanandaji Maharaj.

The last book, his magnum opus, Supreme Knowledge-Revealed through Vidyas in the Upanishads, was first serialised in the magazines 'Divine Life' and 'Wisdom Light' from 1984-1989, and then printed in book form in 1990 with some valuable additions. A second edition was published in 2000. Just a few months before his demise, Swamiji was surprised and pleased to receive a copy of a magazine review of The Supreme Knowledge. It was a full page book review written by Sri Ajit Telang in the magazine DILIP. Mr. Telang wrote: "His Holiness Swami Brahmanandaji Maharaj has done a remarkable service to the readers of spiritual books by coming out with this book. The author has provided unique spiritual insights from the Upanishads that are valuable tools to the seekers of the eternal truth-Brahman....Swamiji explains the ideas of the Upanishads and their relevance in today's life so well that the book can practically become a text book for any spiritual aspirant, who wants... to make progress on the spiritual path."

Through the pages of his writing, Swamiji has unveiled many enigmatic scriptural statements by explaining the esoteric significance and the hidden meaning of the text beyond and above etymological and common meaning. As he often said, "You must read behind the words and between the lines when studying the scriptures. Do not take them literally. There is something hidden there." Undoubtedly, he has put forth his visions and contemplations in these pages.

Towards the end of 1998, two video cassettes were released containing recordings of eight classes taught by Swamiji on the Karika to the Mandukya Upanishad. These were the last formal classes taught by Swamiji prior to his stroke in December 1995. Also released were five audio cassettes containing the first ten classes of a one hundred-ninety-eight class series by Swamiji on St. Jnaneshwar's Amritanubhava (Experience of Immortality).

Generally, throughout his life, Swamiji enjoyed very good health. Naturally, he was endowed with a strong physique. Meticulously, he observed physical cleanliness. In his younger days, he would bathe daily in the Ganga and take long walks. The walking continued up to his final years. His daily routine and his dietary regime were both impeccably adhered to. He observed moderation in all matters, especially food habits. For more than half a century, he took only one tablespoon of rice with his lunch, which otherwise included a small amount of vegetable, dahl or sambar, perhaps a chapati and some curd. Dinner was the same every evening: kitcherie and a little dahl. On rare occasions, Swamiji himself would prepare dosa in his room, mixing the batter in his single small catori and cooking it on a well-tempered cast iron skillet. Because of these simple food habits, he never experienced indigestion or headache or the other symptoms associated with poor digestion. Once an Army Medical Officer from Dehra Dun visited the Ashram. He also came to see Swamiji. He made a general check-up of Swamiji and finally made the remark, "Today, for the first time, I am seeing a young man of eighty years!"

Swamiji was gentle, unassuming and respectful. He had a naturally serene personality. He was soft-spoken, patient, calm and kind to everyone and everything. Whatever he touched, he touched with gentleness. One could never hear even his foot-steps. If any new thing was brought into his presence, Swamiji evinced a childlike curiosity and delight in delving into its workings and mechanisms. Whenever he used to walk though the Ashram premises, he would observe the new construction and would ask details about it. He was extremely observant about everything that was happening, extremely aware. Swamiji displayed love, care and concern regarding the welfare of sadhaks whom he knew. If those known to him were absent for more than a few days, Swamiji would send someone to get news of them. If someone were ill or injured, Swamiji himself would go to his bedside and make sure he was receiving the proper care.

Once, one resident-sadhak started playing badminton with some other sadhaks. Although Swamiji advised him not to play, he did not heed Swamiji's advice. Within a few days, he sustained a fracture of one of his legs and was confined to his room for three months. Swamiji said nothing, but instead, would climb two flights of stairs to visit him in his room. On another occasion, two close devotees of Swamiji accompanied him on his evening walk. While Swamiji was sitting on the Ganges bank, the two devotees (against Swamiji's wishes) started swimming and sporting in the water. The tide was high and the current swift. Swamiji called them back repeatedly, but they were not listening. Suddenly two policemen appeared, compelled the two swimmers to return to the bank, and gave them a sound scolding. Swamiji just smiled at them. Even if it were a matter of egregious conduct on the part of one of the sadhaks, Swamiji never rebuked him to his face nor spoke against him to others. He was a paragon of equal-vision, acceptance and compassion.

Swamiji led a simple life. One could not find expensive or luxury items in his room. He lived with minimum comforts. Once, in the summer season, a Brahmachari from the Reception Office brought an air-cooler to Swamiji's room. Swamiji smiled and allowed him to turn it on. The Brahmachari returned with the satisfaction of having given some relief from the summer heat to the aged body of Swamiji. The next morning, as a first duty, Swamiji phoned the Brahmachari and lovingly asked him to take back the cooler as he did not need it. Swamiji was also very considerate regarding his elderly Swami neighbours. Because Swamiji was conducting classes, many students would come to see him for consultation and might also present him with various items like biscuits, etc. Swamiji always shared these items with his neighbours. And, when sitting outside on the verandah with his neighbours, he made it a point to include them in conversations with students.

For almost thirty years, Swamiji lived in a modest room located on the ground floor of the men's quarters behind the Viswanath Mandir. It was approximately eight foot square, with an area two feet by six feet sectioned off as a bath-toilet. There were two small windows. Ventilation was poor. There was no closet. Clothing was neatly folded and hung over wire clothes-lines placed along the wall. Swamiji had a small metal bookshelf, the top of which served as his altar. On this he had placed the sacred photograph of Gurudev Sri Swami Sivananda, which was flanked on either side by a small brass vase filled with red flowers. In the centre was the ghee lamp, a holder for incense, and a few other articles for daily worship. Below this, on the first shelf of the book-rack, Swamiji placed some articles of personal use: his fountain pen, a pen knife, some toothpicks, a note-pad, Everything was kept in the right place, its exact place, and it was a place of maximum utility. One could not find a better location than Swamiji's choice. Swamiji used to light the ghee lamp and incense both in the morning and evening. In the morning after lighting the camphor, he used to chant Guru-stotras and Para-puja slokas. He always took care that the best quality ghee was used in the lamp, and that it was lighted at the proper time.