BUDDHA

DAILY

READINGS

Compiled from various sources

By

Swami Venkatesananda

With foreword by

H.H. Geshe Rabten

H.H the Venerable Piyadassi Maha Thera

H.H. the Venerable Dr. Ellawala Nandisvara Nayake Thero

Contents

(The chapter numbers, where relevant, are given in brackets)

The First Discourse-23-25 Jan.

Bodhipathapradipam.. 28,30July.

22 sept. Abhidhammattha Sangaha

Vajracchedika Sutra-24-26 0ct.

Mahayana Sangraha Sastra-8Dec.

atta-dipa bhikkhave viharata

atta-sarana ananna sarana,

dhamma-dipa dhamma-sarana

ananna-sarana

O monks, live with your own self as the lamp and refuge, with no other refuge; live with the dhamma as your light and refuge, with no other refuge.

(Digha Nikaya 26)

na subhute margena bodhiḥ prapyate na amargena:

bodhir eva margo marga eva bodhiḥ

O Subhuti, enlightenment is not attained via a path, nor is it reached without the path: enlightenment itself is the path, and the path itself is enlightenment.

(Prajnaparamita Sutra)

If any one would speak of the non-existent as existent and of the existent as non-existent, then he would not be the all-knowing person. The buddha, the all-comprehensive in understanding, speaks of the existent as existent and of the non-existent as non-existent. He does not speak of the existent as non-existent, nor of the non-existent as existent; he just speaks of things as they are in their true nature...The sun for example does not make anything tall or short nor does it level all things down to the ground. It illumines all things equally. Even so is the case with the buddha. He does not make the non-existent existent nor the existent non-existent. He always speaks the truth; and by the light of his wisdom he illumines all things.

(Maha-Prajnaparamita-Sastra)

First Edition: 1982 (3000 copies)

ISBN o 620 05937 o

Published by

The Chiltern Yoga Trust,

P.O. ELGIN, 7180,

Cape Province,

Rep. of South Africa.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Grateful thanks are offered to:

H.H. Geshe Rabten, H.H. the venerable Piyadassi Maha Thera and H.H. the venerable Dr. Ellawala Nandisvara Nayake Thero for their gracious Forewords.

Amrita Appadoo, Shanti Etches. Patience Fitzjohn, Erica Leon, Bill Thomas, Doreen Black, Mavis Scott, Swamis Narayani Mata, Ananda. Sushila and Hamsa for thoroughly editing and typing the manuscript.

Kalyan McAlister for typing the whole text for the printers.

Les McAlister and Joyce Wilcock for proof-reading with meticulous care.

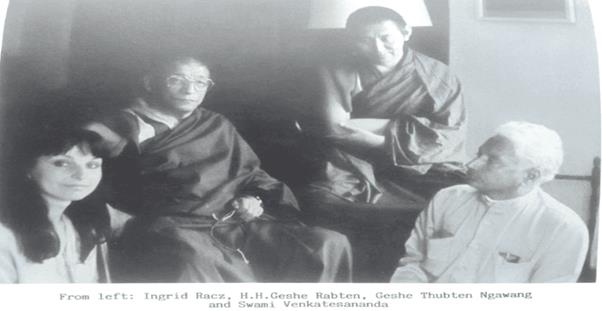

Ingrid Race for organising the audience with H.H. Geshe Rabten. and for the inspiring illustrations.

Heide Ruede, Rebin Featherstone and Sushila for the art work.

Padmavathy for her loving assistance.

Erica Leon for seeing the publication through all its stages.

The following friends of Swami Venkatesananda whose love and support throughout the years, and whose personal offering to Swamiji have helped to make this publication possible:

Mr Mustan Currimjer, Mr V Daya, Val Davidson, Douglas and Sarah February. J.L.G.. Tara Gthwala, Bhikku Kassen and family, Kaschen. Mr and Mrs Satilal Lala. Panos and Sally Lazanas, Bhagavandas Lodhia, Mr G Munsook. Yogeshwari and Irene. Derick and Neela Naidoo, B and Naik and family, the late Mr. Amratlal Naik. Gauri Narotam, Robert and Heima Owens. Mr CC Palsania. the late Mr S Patel, Mra Amboo Pather, Lakshmi and Sanah Pather, the late Chanden Ranchod, Lakshmi and Christie Reddy. Krishna and Sulochana Reddy, Mavis Scott, Fred Stegruhn, Jaya van Alphen, Chidananda-Jyotsnamata and Bharat van der Weeke. Joyce Wilcock and Wesley Zineski.

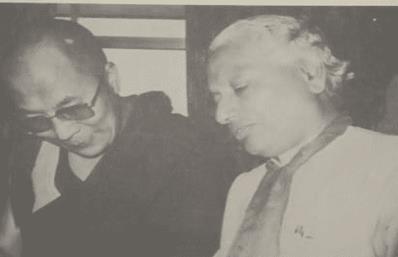

THE DALAI LAMA

H.H. The Dalai Lama's visit to Perth on 20th August 1982 was a memorable one. His Holiness addressed two public meetings at St. George's Cathedral during which he delivered a brilliant exposition of the three aspects of Buddhist teaching: Sila (discipline or right conduct), samadhi (meditation), and prajna (wisdom). During an informal get-together with some of the religious leaders of Perth, he expressed his views on the fundamental issues of Religion strongly reminiscent for me of Gurudev Swami Sivananda's own. Some brilliant flashes are:-

(1) Basically, all religions aim at promoting humanity to make a human being a better human being.

(2) Religions differ in their approach to this aim. The criterion here is 'suitability. Some doctrines suit some people and others suit other people. Some need to believe in a soul, a creator and so on, and others need to believe in self-effort, the law of karma and Investigation.

(3) With the facilities for communication available in the modern world, it becomes urgent that there should be frequent meeting of religious leaders for exchanging of ideas. Common factors should be emphasised, but the differences should not be suppressed.

Swami shows the manuscript of "Buddha Daily Readings" to His Holiness The Dalai Lama

om namo bhagavatyai arya-prajnaparami tayai

arya-avalokitesvaro bodhisattvo gambhiram prajnaparamita-caryam caramano vyavalokayati sma panca-skandhan tam ca svabhavadunyan pasyati ama

iha sariputra rupan dunyata dunyataiva rupan rupan na prthak dunyata dunyataya na prthag rupan yad rupam sa sunyata ya sunyata tad rupam evam eva vedana namjna samskara vijnanam tha sariputra sarva dharmah dunyata laksana anut.panna aniruddha amala avimala anuna aparipurnaḥ

tasmac chariputra dunyatayam na rupai na vedana na samjna na samskarah na vijnanam na cakauh frotra ghrapa jihva kaya manamni na rupa fabda gandha rasa spardatavyadharmah na caksur dhatur yavan na manovijnana dhatuh na avidya na avidya kṣayo yavan na jara maranam na jaramarana kaayo na duḥkha namudaya nirodha marga na jnanam na praptir na apraptiḥ

tasmac chariputra apraptitvad bodhisattvasya prajnaparamitam aaritya viharaty acittavaranah cittavarana nastitvad atrasto viparyasa atikranto nistha nirvana praptah tryadhva vyavasthitab sarva-buddhaḥ prajnaparamitam afritya anuttaram samyaksambodhim abhisambuddhah

tasmaj jnatavyam prajnaparamita maha mantro maha vidya mantro 'nuttara mantro 'samasama mantraḥ sarva duḥkha pranamanaḥ satyam amithyatvat prajnaparami tayam ukto mantraḥ tadyatha gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi avaha iti prajnaparamita hrdayam samaptam

HEART SUTRA

Thus have 1 heard:

The Lord and a great assembly of monks were meditating on the vulture's peak in Rajagṛha.

The arya Avalokitesvara, the bodhisattva, treading the path of the perfection of wisdom which is profound and unfathomable, beheld only the five aggregates, which in themselves were empty of an independent self-existence.

Inwardly prompted by the Lord, the venerable Sariputra asked the bodhisattva: "How should we understand the prajnaparamita?"

Arya AVALOKITESVARA replied:

O Sariputra, form is emptiness and the very emptiness is form; form is non-different (or non-separate) from emptiness and emptiness is non- different from form; that which is form is emptiness and that which is emptiness is form; even so are feelings, perceptions, psychological impressions or tendencies and consciousness.

Here, O Sariputra, all dharma (phenomena or elements) are characterised by emptiness; they are not given rise to nor are they restrained; they are neither impure nor immaculate; neither inadequate nor complete.

Thus, O Sariputra, in emptiness there is no form, no feeling, no perception, no mental impressions or tendencies, no consciousness; no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind; no forms, sounds, smells, tastes, tactile sensations or psychological objects (thoughts and so on); nothing known as the element of sight and so on, up to the element of the mind. There is no ignorance and hence no cessation of ignorance, and so on. There is neither birth and death nor their cessation, no sorrow nor its arising nor its cessation nor a path to such cessation. There is no wisdom, attainment or non-attainment.

Thus, because there is no attainment, the bodhisattva dwells solely in perfect wisdom, without the least veil of mental activity. Because of the absence of this veil, nothing makes him tremble (fear), he has trans- cended whatever is capable of disturbing him and he attains nirvana in which he remains firmly established.

All the buddha in the three periods of time are established in the perfection of wisdom and are therefore fully awake to the right and perfect enlightenment.

Therefore one should know the prajnaparamita mahamantra which is supreme knowledge, supreme mantra and which remedies all suffering and sorrow in truth, for it is true. Here is the mantra declared in prajna- Paramita: "Gone, gone, gone beyond, gone totally beyond, the awakening, svaha.

This compilation of the gospel of lord Buddha has been of great inspiration to me. I have read the pali text where available. I have consulted a few translations but have not always followed them. The translators differ in their interpretation and use of certain key words. This is natural. However much we strive to create uniformity in the use of words for certain concepts, the diversity will continue. Uniformity in this case might even give rise to false images in the minds of readers, thus blocking correct understanding. Hence I have used several words to translate a text which is repeated in different contexts, in the hope that when the buddha's teaching soaks through, the right meaning will emerge from within.

For instance, I read a learned article by a great buddhist scholar in which he declares that saddha is 'confidence rather than 'faith'. This seems to make sense, till we use 'confidence freely and reduce it to 'faith'. The solution seems to be to use several words, each appropriate to the context. This applies to words like viriya which could mean energy, vitality, zeal and so on; samma which can be translated into 'right' and 'perfect'; kusala which has the connotations of skilled, disciplined, good and so on. To help the reader, some words and their meanings gleaned from a standard dictionary as well as the "Manual of Abhidhamma" have been given in the glossary (What are They). Please refer to this before commencing your study of the text.

The teaching has been arranged with the student-seeker's practical needs in view. In addition to the Vipassi story which sounds like the biography of lord Buddha, a few interesting Jataka stories have been included. It is interesting to see that the Prajnaparamita reading for December 3rd mentions that buddha chooses to be born as animal for reasons different from past karma.

I have endeavoured to present the teaching without making it highly philosophical or intellectual, so that a true seeker belonging to any religion might find inspiration in his daily practice of the precepts of the Lord. With this wish and prayer this volume is offered as a flower at the feet of my Gurudev in your heart.

I am grateful to the great living embodiments of the buddha for their gracious Foreword.

Swami Venkatesananda August 1981

Gurudev Swami Sivananda and Swami Venkatesananda at the Kelaniya Budha Vihara (Sri Lanka) during Gurudev’s All India Tour in 1950

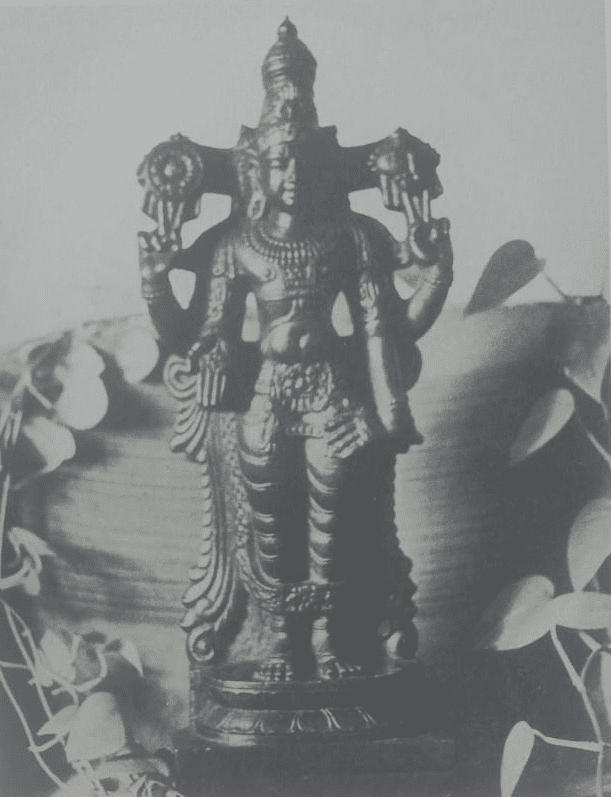

Lord Venkatesa

Facing Page

The bodhisattva Avalokitesvara who gazes upon this world of suffering with eyes of unlimited compassion. i

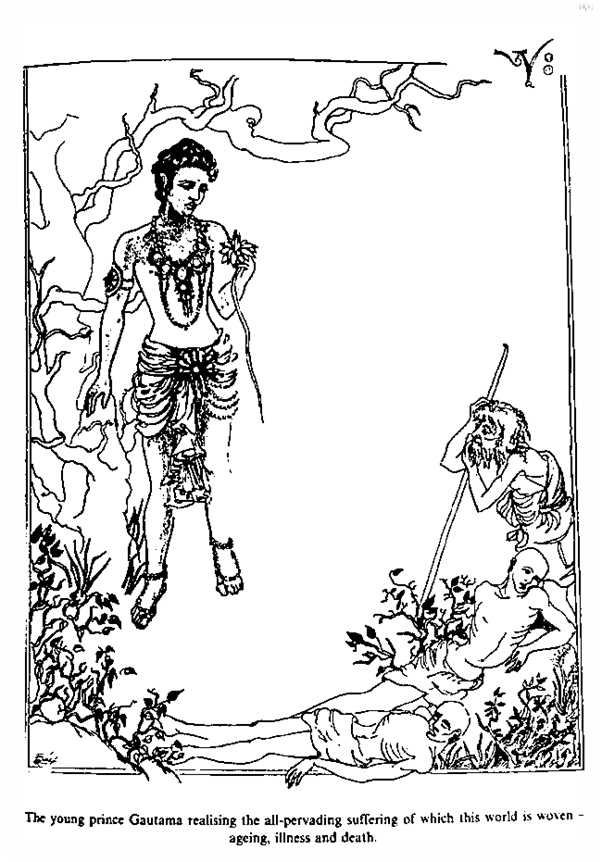

The young prince Gautama realising the all-pervading suffering of which this world is woven: ageing, illness and death. 2 January

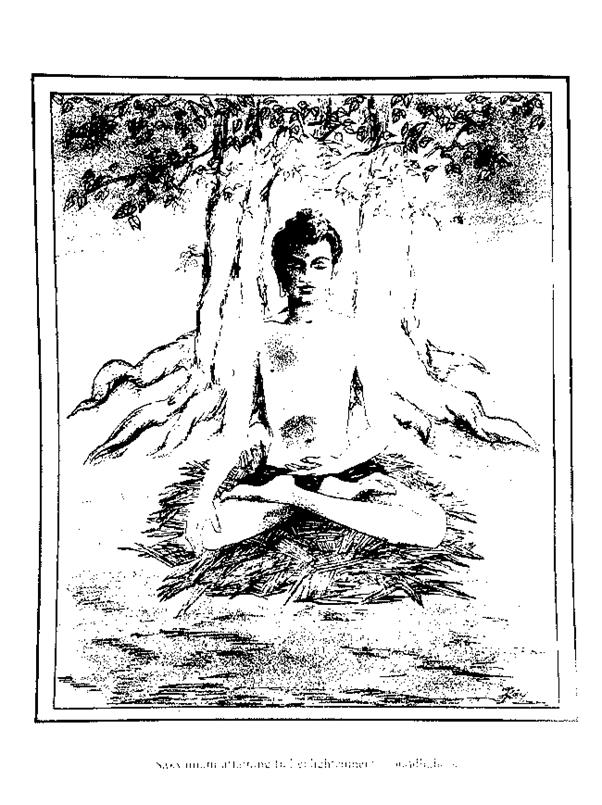

Sakyamuni attaining full enlightenment - buddhahood. 3 January

Buddha teaching his close disciples. 4 February

Entering the fourth meditation. 7 April

Milarepa, the perfect yogi, who fully realised the dharmakaya in a single life-time. 10 June

Buddha Sakyamuni teaching. 13 August

Meditation on limitless space. 16 October

Je Tsong Khapa, considered to have been an incarnation of Manjusri, the bodhisattva of wisdom, whose symbols are the sword and a text book.

18 November

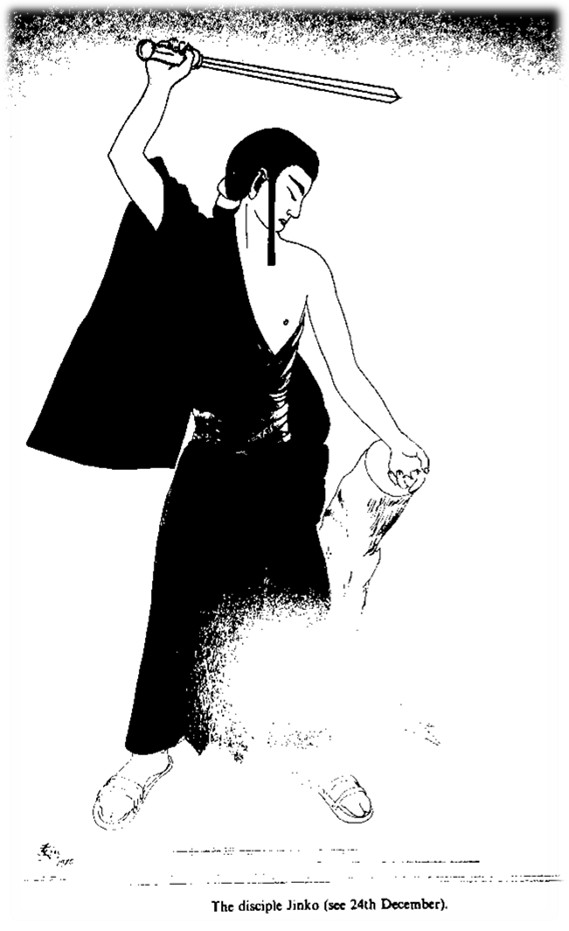

The disciple Jinko. 12 December

FOREWORD

H.H. GESHE RABTEN

The personal adviser to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and a great authority on Vajnayana in particular, and buddhism in general; head of TARPA CHOELING Centre for Higher Tibetan Studies in Switzerland.

First I must offer my respects to Swami Venkatesananda not just as a great scholar but as one genuinely engaged in working for the welfare of others. In addition to performing the altruistic task of propagating the teachings and practices of his own tradition, in this present work he has translated into English and explained some of the Buddhist scriptures. This in itself is a remarkable and worthwhile achievement. Moreover, the Buddhist teachings are of particular relevance today since they are presented in a way that is neither too complicated nor too simplistic. They are easy to practise, they are supported by logic and reasoning, and they produce results for each individual in accordance with his or her particular capacities. Therefore, this work should not be of interest merely to scholars of Buddhism, but should be of benefit to people in all walks of life.

I have the firm conviction that this book will help to lead beings into the supreme Mahayana path of the Vajrayana and thereby assist them in achieving the goal of Buddhahood.

May all mother and father sentient beings find happiness.

May all lower realms of existence cease to be,

And may the prayers of all Bodhisattvas

Everywhere be fulfilled.

Through the virtue of this work

May all beings complete the accumulation of merit and wisdom,

And attain the two holy bodies of Buddha

That arise from such merit and wisdom.

Geshe Rabten

Switzerland, 1980

(Translation of the Tibetan text which appears on the previous pages)

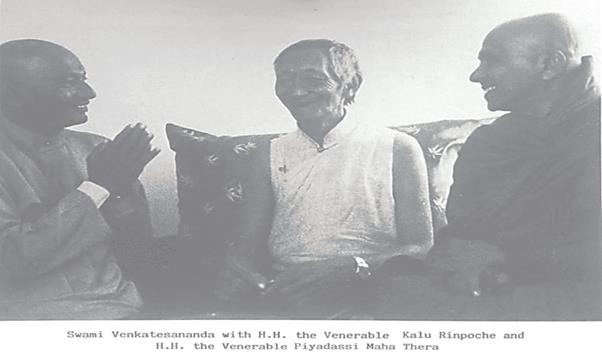

FOREWORD

THE VENERABLE PIYADASSI MAHA THERA

A senior elder Maha Thera- of the Theravada School of Buddhism; the Abbott of the Forest Hermitage, Kandy, Sri Lanka; and the founder of Buddha Viharas throughout the world.

Swami Venkatesananda is known to me for a long period of time. He has his followers in many countries. With their assistance he is making an effort to spread the message of Ahimsa, non-violence, and peace. In recent times he has been translating some of the Hindu scriptures such as Bhagavad Gita, Yoga Vasistha etc., and presenting them as 'daily readings'.

Now the Swami has embarked on a new undertaking the printing of the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha. In this volume the reader will find a selection of the discourses from Digha and Majjhima Nikaya (the long and middle-length sayings of the Buddha). He also has included in this volume teachings of the Mahayana, Tibetan and other Buddhist schools.

Buddhism is the most psychological of religions and in Buddhism there is no coercion and compulsion, instead there is absolute freedom of thought and speech. It is interesting to note what the Buddha has said referring to his own discourses:

"Now this I say, Nigrodha, not wishing to win pupils, not wishing to make you fall from your religious studies, not wishing to make you give up your mode of living, not to establish you in things accepted by you and your teacher as evil and unwholesome, or to make you give up things regarded by you and your teacher as good and wholesome. NOT SO."

"But, Nigrodha, there are evil and unwholesome things not put away, things that have to do with defilements...it is for the rejection of these things that I teach the Dhamma (the doctrine); walking according to which things concerned with defilements shall be put away, and wholesome things that make for purity shall be brought to increase and one may attain, here and now, the realisation of full and abounding insight."

(Uḍumbarika-Sihanada Sutta, Digha-Nikaya, Sutta 25). Western interest in Indian thought, yoga and meditation is increas- ing at an amazing rate. The reason is not far to seek. There is a mounting feeling of restlessness among the people the world over. This feeling is prevalent mostly among the youth. They want a quick remedy for the turmoil of the materialistic world. They are in search of peace and tranquillity.

Here then is the universal lesson the Buddha taught all mankind: the lesson of virtuous conduct (sila) that leads gradually to tranquillity (samadhi) which step by step graduate into emancipating wisdom (panna) and culminates in deliverance (vimutti) which is Nibbana.

So here the perplexed will find clarity, the distraught solace, and the disheartened hope and courage. The discourses of the Buddha have exercised a deep and abiding influence on the course of human thought, and therefore, on the course of human conduct. They have shaped the minds and fashioned the lives of men and women for centuries. Verily it is a timeless message.

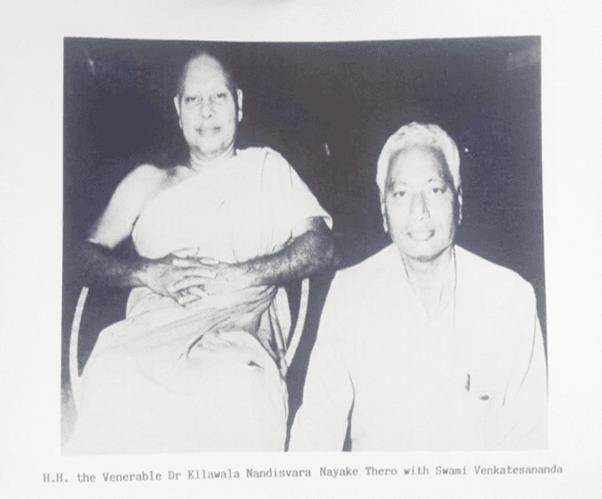

FOREWORD

DR. ELLAWALA NANDISVARA NAYAKE THERO,

M.A., M.Litt., Ph.D.

Director, Maha Bodhi Society, Madras.

I have profound delight and pleasure in adding a foreword to Swami Venkatesananda's book of readings from the Lord Buddha's teachings, for daily perusal and study. The time-honoured teachings of the Lord, though more than two thousand years old, have the greatest appeal to the modern world deluded in torpor, misconception and gross materialism. Time does not wither nor custom stale the eternal truths of suffering, the enhancement of suffering, the cessation of suffering leading to the path of bliss of nibbana. The noble eightfold path is one of spiritual sublimation and perfection of vision to all worldlings seeking the realisation of the supreme truth of the reality of the ultimate goal of man. Man is a temporary sojourner on a rotating wheel of life, living in constant uncertainty of the past, fear of the present and anxiety of the future. Recurring doubt, restlessness, ambition unrealised, cares and distress, agony and travail pursue him like the shadow day and night. Sunk in the depths of utter ignorance he gropes in darkness unaware of the nature of suffering in the world of matter and mind.

The nature of consciousness that sparks the urge of life and goads the continuity of the flux of constant repetition of the desire to live, anchors the mind in the world of becoming. Man is a product of his mind alone. Mind alone creates the sum total of the five aggregates: form, sensation, perception, conception and consciousness. Mind cloisters, fortifies and dissolves the tendency of urge to become.

Birth is sorrow, living is distress, death is grievous pain. The born are subject to suffering and the unborn suffer not. One who is born is always maturing, ageing, decaying, and under the normal stress of daily living undergoes untold agony as a result of constant innovation. He is a victim to the eternal flux of change, not being the same for two consecutive seconds. All matter within him and without is subject to this nature of revolution and rotation. Where does man find happiness in the midst of such an environment of flux of elements?

Endurance or patience is the noblest form of ascetic practice. Restraint is the highest discipline. Craving is the greatest of all diseases in the life of man. Medicine is capable of remedying diseases that arise in him, but craving is the stark nature of his primordial heritage. It is not curable by external treatment but can be remedied by one's own effort to understand the reality of the world, and rise from its engrossment, realising the futility of attachment to changing phenomena.

The quest for the final goal of peace and sanctity where mortal strife ceases; the flutter of the heart and mind hankering after mundane pursuit (accompanied by greed, hatred and delusion) abruptly culminates in absolute harmony; the stream of consciousness that had interlinked the past with the present and had flowed into the future ever aspiring for repetition of the past experiences under fresh venues completely withered away has been the universal search of man from time immemorial in the history of evolution. Arisen in mortal form his quest for immortality has kindled the beams of light that illumine the pages of philosophical thought. However, the doctrine of the Buddha has not been for the embellishment of the lines of philosophy nor speculative adventure in the field of metaphysics.

The Buddha's main objective was to tackle the main problem of man. Man was born into this world with ignorance of his past conditions. What promoted the present saga of sorrow and reduced his joys and pleasures here, he is at a loss to comprehend. He fails to understand that the past has conditioned the present and the present modulates and determines the future. Lord Buddha endeavoured to dispel ignorance in man's conscious- ness, with his teachings and with rational approach to the law of dependent origination. All beings are products of their past action - the volition in the action determining the extent of preponderance of results He proclaimed. Man had the potentiality and latent power to discover the path of perfection for self-realisation, free from the whims and caprices of super-normal agencies. The Buddha dispelled by his doctrine of enlightenment the shroud of ignorance that veils man's vision from the realities beyond the world of matter. Craving was the cause of all arisings of mind and body in the world of travail. Immediately after enlightenment, in an ecstatic paean of joy, the Lord uttered: "In numerous lives in the ocean of life (samsara) have I been born, all the time seek- ing the creator of this tabernacle of life. I failed to detect the creator but now I have espied him. That creator is none other than the nature of gross craving in me. The mind, engrossed in sensual yearning, thirst- ing for existence and grasping for release from attachment, had for millenniums and millenniums enslaved me to this cycle of existence. Now have I completely and ruthlessly severed the links of the chain of dependent origination that kept me bound in suffering to life and states of woe. This is my last life in any abode of existence. Never more will this sinister nature of craving build the tabernacle of life for me. Shattered are the rafters and ridge-poles that bore it, and destroyed is the yearning or desire to be."

Craving is the root cause of all becoming. That attachment, with greed for repetition of form and mind, gives joy hither and thither in varying forms of life, urging the gratification of the senses, the fulfilment of the desire to exist and a constant yearning for the ultimate cessation of desire itself. Desire begets pain and sorrow in the inability and inadequacy of attainment. The urge in man is for the plenary perfection of life in the aspiration for bliss. Bliss is the state of total release from all desires (or desirelessness).

The teachings of the Buddha emphasise the latent power of man to redeem himself from the stream of becoming, unprejudiced by the whims and caprices of super-normal powers. "Within this fathom-long body is the arising of the world, and its cessation. You are your own guide and master upon the path; why look for external aid for your liberation? The Buddhas do not cleanse and purify you. They show you the path of perfection and liberation. Through their teachings purify thy mind and attain to the state of deathlessness, utilising thine latent powers."

Buddhism does not accept the theory of creation of the world by any super-normal power but ascribes the world to be in constant flux, constantly evolving or devolving with its geological nature, creativity and destructivity. Man and nature are subjected to the flux of change, therefore consistency is not a quality of any phenomenon.

The stream of life is a projection of the mind heavily loaded with the energies of the flux of consciousness. What is the universal factor in all emanations? The Buddha states: "Mind alone is the primeval factor in all emanations of form. Mind alone prevails and preponderates." Buddhism substitutes the mind in the place that soul occupies in other theistic religions. Mind alone makes or mars man.

The principles of simplicity, austerity and renunciation embodied in the teachings of the Lord Buddha exemplify that humility, chastity and poverty, though self-imposed, contribute towards the gross contentment of the mind of the aspirant for mental solace. The tattered robes of the monk with his begging bowl stands as the perfect symbol of complete renunciation of all worldly wealth. Happy is he with the humble food offered by the impoverished urchin and the robes he stitches together from the tatters he picks off the funeral disposals.

Buddhism has often been called a pessimistic teaching, as the key note of the doctrine emphasises the truth of suffering, the enhancement of suffering. The universality of suffering in this world is apparent to the poet and the philosopher, but not to the worldling who constantly pursues the gratification of the carnal senses. Even to him, a reflection arises that inability to gratify himself in his urges is sorrowful. Not to attain what one desires is sorrow. The separation from loved ones is suffering and painful, to be with those who are undesirable again is regretful. These sorrows are stressed as there is a state free from suffer- ing that could endow the state of perfect peace. There is a state of peace where sorrows end, where birth and craving cease, where birth, decay and death end. This state can be attained within this mortal frame. Assiduously and earnestly endeavour to reach this state, O monks, and your sorrows shall end.

Quotations from the Pali text have been included in the selection of readings to enlighten the reader on the noble eightfold path: right under- standing, right thought, right word, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration. In the key note exposition of the dhamma to the first five disciples in the Deer park at Varanasi, the Lord Buddha expounded the middle path of ascetic practice, neither leaning to the extreme view of self mortification nor self indul- gence, both of which he declaimed as non-conducive to the final attain- ment of nirvanic bliss. This middle path is the noble eightfold path. The Tathagata, by following this middle path, attained to the highest liberation and enlightenment. It is with the clear perspective of super- normal vision into things mundane and supramundane that the Blessed One reveals the four noble truths and the noble eightfold path for the absolution of suffering here in order to attain the state of deathless emancipation.

The attainment of nirvana is no prerogative of a selected few. It is within the perspective of all who follow the middle path and assiduously practise the fourfold mindfulness. Swami Venkatesananda has brought out the salient features of the four Satipatthanas in his selections from the texts and this will be of enthralling delight to the peruser.

Nirvana is not a nihilistic negation of life. It is a positive state of attainment where the fires of desire that kindle the life-urge come to a peaceful cessation. It is not a state of merging with infinity of space or time, nor with infinity of divinity. It is a state of the con- ditioned mind attaining the unconditioned. The fires of material urge in the planes of mundane existence are chilled and the mind enters the bliss of release from the world of becoming. The continuity of the life-stream withers away as sensual desire, desire to continue and the inclination for satiation (kama tanha, bhava tanhã, and vibhava_tanha) no longer feed the flux of life. The purified one who enters nirvanic bliss negates the effect of all karma and results thereof arising in the future, but is still subject to the after effects of any residue remaining unspent in this life-time.

I am indeed deeply indebted to the efforts of Swami Venkatesananda who, with great patience and assiduity, has compiled the text of readings from the Pali Texts, adding a few selections from the mahayana and the sarvastivada schools. The bodhisattva ideal of mahayana thought has been of immense appeal to the world and the bhakti cult arising out of practices in China and Japan has motivated a sense of profound sacrifice and self-surrender both to the Buddha and the dhamma. The bodhicitta of the sarvastivada school of Tibet has awakened the ecstatic poetical utterances of Milarepa, who opens his mind and heart of absolute purity and innocence to the throbs of the deluded world of yearning consterna- tion and ego-centricity.

May the light of the dhamma be your guide each day of your reading, and may the path of enlightenment be within your reach in this life itself. May all beings in this world and all sentients in other realms of life attain the bliss of nirvana.

H.H. Swami Pranavananda of the Divine Life Society, Malaysia, H.H. the Venerable K Sri Dhammananda Thera, and Swami Venkatesananda

I have gone through your article concerning the life of Lord Buddha and found it to be suitable for publication.. I have nothing to add or delete. I am happy to enclose in this letter your article and trust it will reach you in good order.

VENERABLE K. SRI DHAMMANANDA THERA

Chief High Priest in Malaysia.

The historian has been able to determine that the Buddha was born in the year 563 B.C. Buddha (or, Gautama Siddhartha as he was known) was born of king Suddhodana and his queen Maya. King Suddhodana was then ruling over a kingdom in North India. One day the queen dreamt that the guardian angels of the earth lifted her and took her away to the Himalaya and there she was bathed in the Anotatta lake and laid down to rest on a heavenly couch within a golden mansion on Silver Hill. Then the bodhisattva destined to become the buddha entered her womb.

A bodhisattva is one who has almost reached perfection, who possesses all the qualifications necessary for attaining buddhahood. This was the last birth for this particular bodhisattva. Queen Maya related her dream to the king who consulted the learned men of his time, who predicted that the queen would give birth to one who, if he remained a householder would become the king of the earth, and, if he adopted the monastic life, would become the buddha.

These great ones are often born in unexpected environments. The buddha was born in a 'pleasure-grove of sal-trees', and it is said that "four brahma angels received the child in a golden net (as it was being delivered by the queen) and showed it to the mother, saying: 'Rejoice, O Lady! A great son is born to thee." It is added that he immediately stood up and took seven strides proclaiming that he was supreme in the world and that this was his last birth.

The child was named Siddhartha. The king eagerly sought the advice. of fortune tellers to avert the inevitable. The wise men predicted that Siddhartha would be reminded of the purpose of his life by the four signs: old age, sickness, death and a monk. It was easy, so the king thought, to avert destiny; he could ensure that the prince would never see any of these.

Seven days after the child's birth, queen Maya passed away. Freed from maya, the great power of illusion, the young prince grew up.

As was the custom the prince was sent to a teacher (acarya). Siddhartha excelled in all arts and crafts that were taught to him. At the same time, the worried monarch spread a net of pleasure, pastimes and prosperity around the prince to capture the bird destined to fly away! Several palaces with all manner of objects of pleasure beyond the reach of even others of the princely clan were built to imprison the future buddha who was born to liberate the spirit of all men. The king was even more thrilled when the prince consented to marry, and lost no time in securing for him the hand of one of the most eligible maidens of the time, Yasodhara. The prince lived what was outwardly a normal life with princess Yasodhara, and they had a son.

Even before the son was born, the mission for which Siddhartha was born had to be fulfilled. During his excursions from the palace, Siddhartha encountered, one after the other, an old man, a sick man and a funeral procession. Siddhartha questioned his charioteer: "Is this the common lot of all?" The charioteer in all honesty had to affirm it. When they met the bhikkhu (mendicant ascetic), Siddhartha asked the charioteer: "Who is this man clad in rags who radiates peace and bliss?" The charioteer had to answer: "This, O Prince, is a bhikkhu who has renounced the world." That was the answer the prince was waiting for. In the silent darkness of the night, the prince left the palace, and in the manner of the men of renunciation, Siddhartha cut off the locks of hair, discarded the princely attire and donned the robes of a mendicant. Siddhartha commenced his journey to the destination- nirvana.

For a time Siddhartha became the 'disciple' of Alara Kalama who, however, did not satisfy the disciple. Siddhartha left him and reached the Uruvela forest where he joined a company of five extremist ascetics. For six years he practised the severest form of austerities. His body wasted away. But where was the advantage of destroying the body which would fall one day without all this effort? Siddhartha Gautama realised the error just before it was too late, and resolved to take food. An angel appeared in a dream to Sujata, the daughter of a village chief, and commanded her to offer food to the bodhisattva. On the full moon day in the month of May, she made her offering of rice cooked in milk. Siddhartha's strength was revived. Sujata was blessed.

Siddhartha entered into deep meditation. "In the first watch of the night he reached the knowledge of former states of being. In the middle watch he obtained the heavenly eye of omniscient vision and in the third watch he grasped the perfect understanding of the chain of causation which is the origin of evil, and thus at the break of day he attained to perfect enlightenment. He proclaimed: 'Through many diverse births I passed seeking in vain the builder of the house. But, O builder of houses, thou art found never again shalt thou fashion a house for me! Broken are all thy beams, the king-post shattered! My mind has passed into the stillness of nibbana; the ending of desire has been attained at last.""

Siddhartha Gautama had become the buddha. The buddha's enlighten- ment lightened the burden of all mankind. For seven weeks thereafter Buddha enjoyed the bliss of nibbana. Afterwards he set out to teach the truth that he had realised.

The mission had begun. The buddha enlightened a thousand disciples. He went to his father's capital, Kapilavastu. The king became Buddha's follower and the royal household followed suit. Buddha's son, Rahula, became his disciple. The swelling congregation of Buddha's followers took the shape of the holy order, the sangha. The buddha continued to tour the country, preaching the dhamma and leading thousands along the noble eightfold path. Lord Buddha was perhaps the first Indian founder of a religious sect who organised his followers and established an order. He even formulated the rules and regulations of the order.

The mission was drawing to a close. The buddha had announced that soon he would be discarding the body. Some of his disciples were stricken with grief. To console them and to admonish them, the buddha instructed them thus: "Therefore, be ye lamps unto yourselves. Be ye a refuge to yourselves. Betake yourselves to no external refuge. Hold fast to the truth as a lamp. Hold fast as a refuge to the truth. Look not for refuge to anyone besides yourselves."

It is said that the buddha partook of a meal served by Cunda the smith which upset his digestion and eventually caused his death. There has always to be some reason. The buddha himself warned his disciples not to blame Cunda. He even compared Cunda's offering with Sujata's: the one immediately before the enlightenment and the other immediately before the final passing away. As he lay during the final hour of his last incarnation on the earth, he consoled everyone near him, and passed away with these words: "Decay is inherent in all component things. Work out your salvation with diligence."

Father Paul Bossard of the Swiss Catholic Mission, says:

"It is worth mentioning that Buddha was regarded a 'pre- christian saint'

in the Catholic church until the 12th century,

his name being listed in the 'Martyrologium',

an index of great men and women who gave special

witness to God and Christ through their life and teachings."

PUBLISHER'S NOTES

The day-to-day style of this publication follows the same pattern as The Song of God (Bhagavad Gita), Bhagavatam (The Book of God), Valmiki's Ramayana and The Supreme Yoga (The Yoga Vasistha). Such a diarised presentation greatly facilitates study of these sacred texts.

The use of capital letters has been reduced to the absolute minimum. For the plural form of many of the pali and sanskrit nouns such as: asava, brahmana, buddha, deva, an accent has merely been added to the last vowel regardless of the proper form. We crave the indulgence of pali and sanskrit scholars for this.

On certain pages a pali or sanskrit quote has been selected and is given at the top of the page. The free translation of that quote can be found in bold face in the body of the text. The top left-hand side of the page indicates the source and the right-hand side the chapter number, where relevant. For example:

DIGHA NIKAYA 31st DECEMBER 34

IMPORTANT

1. "Thus have 1 heard" is how the pali text commences every sutta. The narrator is Ananda.

2. Where the main text is short of a full page, 'fillers' have been used. These have been chosen at random and do not have a bearing on the text on that page.

PRAYER BEFORE THE DAILY READING

buddham saranam gacchami

dhammam saranam gacchami

sangham saranam gacchami

dutiyampi buddham saranam gacchami

dutiyampi dhammam saranam gacchami

dutiyampi sanghan saranam gacchami

tatiyampi buddham saranam gacchami

tatiyampi dhammam saranam gacchami

tatiyampi sangham saranam gacchami

1 take refuge in the buddha,

1 take refuge in the dhamma,

I take refuge in the sangha.

For the second time,

I take refuge in the buddha, dhamma and sangha.

For the third time,

1 take refuge in the buddha, dhamma and sangha.

PRAYER AFTER THE CONCLUSION OF THE READING

etena sacca vajjena sotti te hotu sabbada

etena sacca vajjena sabba rogo vinassatu

etena sacca vajjena hotu te jaya mangalam

sabbhitiyo vivajjantu sabba rogo vinassatu

ma te bhavatvantarayo sukhi digghayuko bhava

bhavatu sabba mangalam rakkhantu sabba devata

sabba buddhanubhavena sabba dhammanubhavena

sabba sanghanubhavena sada sotti bhavantu te

nakkhatra yakka bhutanang papaggaha nivaranang

paritassanubhavena hantu te sang upaddave

devo vassatu kalena sassa sampatti hotu ca

pito bhavatu loko ca raja bhavatu dhammiko

1. By this avowal of truth, may you ever be well. By this avowal of truth, may all disease be destroyed. By this avowal of truth, may joyous victory be thine.

2. May all misfortunes be warded off, all diseases cured, and no danger befall you. May you live long in peace. May all blessings be yours. May all gods protect you. By the power of all the buddha, by the power of all dhamma, and by the power of all the sangha, may happiness ever be yours.

3. By the power of this protection may no misfortune result through stars, demons, evil spirits and evil planets. May your troubles come to an end.

4. May there be rain in due time. May there be a rich harvest. May this world be contented. May the kings be righteous.

vipatti patibahaya sabba sampatti siddhiya

sabba dukkha vinasaya parittam brutha mangalam

vipatti patibahaya sabba sampatti siddhiya

sabba bhaya vinasaya parittam brutha mangalam

vipatti patibahaya - sabba sampatti siddhiya

sabba roga vinasaya - parittam brutha mangalam

Chant this protection so that you may be freed from misfortune and all good fortune may come to you; so that all sorrow, fear and disease may come to an end.

BUDDHA

DAILY READINGS

14

dhi-r-atthu kira bho jati nama yatra hi nama jatassa jara

pannayissati, vyadhi pannayissati, maranam pannayissatiti

Thus have I heard:

The Lord was staying in Savatthi in the Jeta grove. One day, on the grounds nearby, the monks had come together after their alms gather-ing and meal. There arose among them a discussion concerning previous births. The Lord had heard this with his divine ear, and had arrived at the scene. The monks had told him what they were discussing and prayed that the Lord might discourse to them upon the subject.

The LORD said:

Ninety-one aeons ago the Buddha Vipassi arose in the world in a noble family, lived for eighty thousand years and had millions of disciples. Thirty-one aeons ago the Buddha Sikhi was born in a noble family. He lived for seventy thousand years and had a million disciples. In the same aeon the Buddha Vessabhu appeared in a noble family, lived for sixty thousand years and had over a million disciples. In this, our aeon (kalpa), there have been three other buddha Kakusundha, Konagamana and Kassapa who were all of brahmana parentage and who lived for forty, thirty and twenty thousand years respectively and had the same number of disciples. I have arisen as the buddha in this world, and through clear perception of the truth I have realised what the gods have revealed to me.

When a bodhisatta ceases to belong to the heaven of delight, he descends fully and mindfully into his mother's womb: this is the rule. There are other conditions which mark the descent of the bodhisatta. At that time an incomparable radiance fills the atmosphere, four guardian deities guard him in the four directions and the chosen mother is virtuous by nature. Though she enjoys the objects of the senses, she does not indulge in sensual pleasures with men. She is totally free from all ailments, she sees the bodhisatta in her womb, complete in all detail. She bears the child for ten full months and she delivers him standing. He is received first by the gods who present him to the mother. He is born pure, undefiled by the fluids of the womb. At his birth there is a shower of both warm and cold waters which bathe the babe and even at birth he stands up (with a white umbrella held over his head) and roars: "I am the foremost among beings and this is my last birth."_

Such was the birth of Vipassi. His father called upon the brahmana soothsayers to foretell his future. They saw the thirty-two marks of the superman on him and said: "If he remains a householder, he will be emperor; if he renounces the world, he will be a buddha." Since the baby could already see kamma clearly, he was called "Vipass" (vipassana clear sight). There was another reason. His father used to keep him on his lap while holding court, knowing that his judgements came from the baby who 'could see the truth'.

The father had Vipassi surrounded by objects of pleasure. But Vipassi went to the park on four occasions and encountered an old man, a sick man, a dead body and lastly a wandering mendicant. From the driver of the chariot he learnt that all beings were subject to old age, sickness and death. He said to himself: "Fie on this birth which is the source of old age, sickness and death."

2nd JANUARY

nirodho nirodho ti kho bhikkhave vipassissa bodhisattassa

pubbe ananussutesu dhammesu cakkhum udapadi nanam

udapadi panna udapadi vijja udapadi aloko udapadi

The LORD continued:

After some days Vipassi went out in his chariot. He saw a shaven-headed man wearing a yellow robe and asked the driver: "Who is he? Why is his head shaven and why does he wear the yellow robe?" The driver replied: "My Lord, he is a wanderer who has gone forth from home to a homeless state and a religious life which is full of good and meritorious actions and loving kindness." Vipassi resolved then and there to enter the homeless life. He cut off his own hair and put on the yellow robe. Seeing this, thousands of members of the royal court also did so and followed him. But he resolved to live in seclusion and went away from them.

There Vipassi contemplated: "Surely this world is full of sorrow and there seems to be no escape from it. What is the condition ante- cedent to old age and death? Birth. What is the condition antecedent to birth? Becoming. Similarly, grasping (attachment) is the condition for becoming, craving for attachment, feeling for craving, sense-contact for feeling, the sixfold field for sense-contact, name-and-form for the sixfold field and cognition for name-and-form. These act upon each other and cease in the same order, but in reverse. If the cause is not present, the result will not arise."

In Vipassi there arose the realisation: "I have found the way to enlightenment through insight." (Vipassana - clear sight). Cessation! Cessation! At the very thought of cessation there arose in Vipassi, the bodhisatta, a clear vision, wisdom, awareness, knowledge and light, in regard to what had not been heard before.

Vipassi understood the five forms of grasping (attachment). He knew how form, feeling, perception, synthesis and cognition come into being and cease. He was free from the defilements (asava).

Vipassi contemplated: "Perhaps I should teach this truth to other beings. But then it is subtle, deep, beyond reason and logic and intelligible only to the wise. The people of the world are given to sense- pleasures and hence may find this truth hard to perceive. If I were to teach and the others were not to comprehend, it would be a wearisome task. I shall abandon the idea of teaching the slaves of passion."

But the great Brahma appeared before Vipassi and pleaded: "Let the Lord preach the truth. There are beings whose eyes are bedimmed with dust, but there are also people who will listen and become knowers of the truth. They are perishing because they have not heard the truth."

With the buddha vision, Vipassi gazed upon the world and beheld those whose eyes were not covered by dust. In response to Brahma's entreaty, Vipassi proclaimed: "Wide open are the gates to nibbana; they that hear, let them renounce empty faith."

Sakyamuni attaining full enlightenment-buddhahood.

3rd JANUARY

abhikkantam bhante abhikkantam bhante. seyyatha pi

bhante nikkujjitam va ukkujjeyya paṭicchannam va vivareyya

mulhassa va maggam acikkheyya andhakare va tela-

pajjotam dhareyya cakkhuman to rupani dakkhintiti evam

eva bhagavata aneka-pariyayena dhammo pakasito

The LORD continued:

Having decided to teach the dhamma, Vipassi considered whom he should teach first. He chose Khanda (a king's son) and Tissa (the chaplain's son), for they had very little dust covering their eyes. He sent for them, and when they arrived they saluted the arahant buddha supreme.

Vipassi expounded the doctrine to them in due order. He spoke of generosity, right conduct, heaven, the danger of vanity and the defilement of cravings and the fruits of renunciation. When he discovered that they were free from prejudice and that they had faith in their hearts, he taught them the truth which buddha alone have realised: the doctrine of sorrow, its arising, its cessation and the means to its cessation. Even while he was thus discoursing, Khanda and Tissa gained the divine insight with which they directly realised the truth, and thus knew that whatever has a beginning must also have an end.

Having realised the truth and having been freed from doubt, they said: "Most excellent, Lord, most excellent, Lord. It is as if someone lifted up what had been thrown down, revealed what was hidden, pointed out the right road to one who had gone astray and brought light into darkness so that he could see. Permit us to go forth from the world under the guidance of the Lord. May we receive ordination from the Lord."

Vipassi ordained them and then exhorted them further. Soon they were freed from the asava. All the eighty-four thousand inhabitants of the city, seeing that their own king's son had gone forth from the world, followed his example. They realised that this was no ordinary religious rule and that it was an uncommon going forth into the homeless life. An equal number of recluses also followed their example. Vipassi taught and ordained all of them, and later he bade them to go out and teach humanity. "Go not singly; go in pairs," he told them. "Teach the truth which is excellent in the beginning, in the middle and in the end. After every six years, come back to Bandhumati to recite the patimokkha (the rules of the order)." Even before the first period of six years came to a close there were eighty-four thousand monasteries. When they returned to Bandhumati, Vipassi said to them:

"How can the flesh be subdued? By being patient and forbearing. What is the highest and what is the best? Nibbana, so say the buddha. He is not a recluse who harms fellowmen. Do not blame anyone. Be self- restrained. Live in seclusion. Let your thoughts be ever sublime."

At one time I was living at Ukkaṭṭha. I vanished from there and went to the Aviha heaven. The gods came up to me and told me that it was ninety-one aeons since the time of Vipassi, and also recounted the birth of the other buddha. I also met the cool gods, the fair gods and the wellseeing gods. From them I learnt the lives of the past buddha.

81

Sadhusammatam hi me tassa bhagavato dassanam arahato

samma sambuddhassati

Thus have I heard:

The Lord was sojourning in the Kosala country. He went into the village known as Vebhalinga, and said to Ananda: "Once upon a time, here in this village, there was an enlightened one known as lord Kassapa." Ananda prepared a seat for the Lord, saying: "Then surely this place has had the good fortune of being visited by two enlightened ones."

The LORD continued:

At that time, Ananda, in this very place lord Kassapa instructed a large group of monks. There lived here a potter named Ghatikara who was a great supporter of lord Kassapa. The potter had a brahmana friend named Jotipala. One day the potter tried to persuade the brahmana boy to go with him to meet lord Kassapa, but the brahmaņa boy was reluctant. The potter led him to the river to bathe and there once again suggested: "Let us go and meet lord Kassapa, for such a meeting with the Lord, who is perfectly enlightened, is an event of great merit.' But the brahmaṇa boy refused. The potter repeated the suggestion, and when the brahmaṇa boy consented to go, he grabbed him by the hair and introduced him to lord Kassapa. The potter prayed that lord Kassapa might instruct the boy in dhamma; lord Kassapa did so and both of them were greatly inspired. Now, the brahmaṇa boy asked the potter: "Why do you not receive ordination from lord Kassapa after hear- ing this?" The potter replied: "Because I am serving my aged parents." The brahmana boy, however, entered the homeless state as a follower of the Lord. Soon after that lord Kassapa left that place and journeyed to Varanasi.

In Varanasi, Kiki, the king of Kasi, was greatly inspired by lord Kassapa's teaching and invited him for a meal. Lord Kassapa consented. Then the king suggested that lord Kassapa might spend the rainy season in the palace but lord Kassapa replied that he had already agreed to spend the rainy season with the potter Ghaṭikara.

Lord KASSAPA said:

"Perhaps you feel depressed at the thought that I do not accede to your request, but such is not the case with the potter. He has complete- ly renounced all possessions. He makes pots and lets the people take what they will and leave what they will in return. Once I was staying in that village. I went to his house for alms, but only his parents were there. They asked me to help myself to the food that was in the house and I did so. The potter was delighted. On another occasion the roof of my hut leaked. I sent some monks to see if the potter had some grass with which to repair my hut. He did not. So I asked the monks to strip the potter's own roof and with that material repair my hut. They did so when the potter was not at home. When he learnt of this later, he was supremely delighted that he could thus be of service to me. It rained, but though his house had no roof, rain did not fall in his house."

Hearing this, the king had the requisite provisions sent to the potter's house. Ananda, at that time I was that brahmaṇa boy, Jotipala.

83

patubhuta kho me tata kumara devaduta; dissanti sirasmim

phalitani jatani. bhutta kho pana me manusaka kama,

samayo dibbe kame pariyesitum

Thus have I heard:

The Lord was staying in Mithila in Makhadeva's mango grove. When he came to a certain part of the grove, the Lord smiled. "Surely, there must be a reason for the Lord smiling thus," thought Ananda, and in response to his request, the LORD narrated the following legend:

Long ago, a king named Makhadeva ruled this very Mithila. He lived a very long life, observing all the religious rituals. One day he said to his barber: "When you see gray hairs on my head, tell me." After many thousands of years, the barber announced one day that gray hairs had indeed begun to appear on the the king's head. The king rewarded the barber and then summoned his son and said to him: "Son, messengers from the gods have appeared. There are gray hairs on my head. I have enjoyed human pleasures so far. Now it is time to enjoy the divine pleasures. I shall presently cut off my hair and beard, don ochre robes and enter the homeless life. Come, take charge of this king- dom. In the same way, when gray hairs appear on your head, hand the reins of the kingdom to your son and similarly retire. Let this tradition be honoured by your descendants too."

The king entered the homeless state in this very grove. Having cut off his hair and his beard and having donned the ochre robe, he radiated friendliness in the four directions. Thus freed of all violence, the king lived here for the last eighty-four thousand years of his life. His son, too, followed the father's example and came to this very grove to enter the homeless life. And so the tradition was preserved. The last king to thus enter the homeless life here was Nimi.

While Nimi was ruling Mithila, his name was mentioned in the assembly of the gods, and they were eager to see him. Their chief, Indra, personally went to Nimi and requested him to visit heaven in a special celestial vehicle. Nimi visited heaven but did not consent to stay there. He returned to Mithila, and after many years of righteously ruling the kingdom, Nimi entered the homeless state. His son, however, did not follow his example.

Ananda, I was that Makhadeva who established that good tradition. However, the kings who followed that tradition and practised brahmacariya only gained the world of the creator Brahma. But now I have established another tradition, tradition, which frees people completely from sorrow and leads them to nibbana. and Follow this tradition Ananda, and let it never be abandoned.

Digha Nikaya

19

yava c' assa so bhagava bahujana hitaya patipanno bahujana

sukhaya lokanukampakaya atthaya hitaya sukhaya devamanussanam

imina p' angena samannagatam sattaram n' eva atitamse

Samanupassama Na pan' etarahi annatra tena bhagavata

Thus have I heard:

The Lord was staying at Rajagaha. One day a celestial named Pancasikha approached him and said:

I would like to tell the Lord what happened in heaven. One day long ago all the gods assembled in the hall. Sakka, the king of heaven, addressed the gods: "If it is your wish, I shall enumerate the eight glories of lord Buddha. (1) The Lord has worked for the good of many, for the happiness of many, for the good and happiness of gods and men, out of compassion for the world: in this there is no one equal to him as a teacher in the past or in the present. (2) The Lord has proclaimed a doctrine for the life here and now, but this is not of a transient nature. It is welcomed by the wise who enshrine it in their hearts. (3) He has clearly enunciated that 'this is right' and 'this is wrong', 'this is of the light' and 'this is of the dark'. (4) He has revealed to his disciples the way to nibbana, and the way and nibbana are one and the same. (5) He has students and well trained disciples, whom he does not send away but whom he keeps with him and with whom he dwells in fellowship. (6) Kings admire him and make gifts to him and he is widely renowned; yet he is completely free from pride. (7) The Lord's actions conform to his speech and his speech conforms to his actions, and he has himself strictly adhered to the rules of the discipline. (8) He has crossed the sea of doubt; he has accomplished what has to be accomplished. We cannot find such a teacher in the present nor has there been one like unto him in the past. It is of course not possible that two buddha should arise in the same world- system at the same time."

The gods contemplated what Sakka had said. While they were sitting there an extraordinary brilliance was seen in the north. Soon the Brahma Sanamkumara arrived. Remaining invisible, he expressed his admiration of the Lord and of the gods who were devoted to him. His voice had the eight characteristics of Brahma's voice ... fluent, intelligent, sweet, audible, sustained, distinct, deep and resonant. it was by these characteristics that they recognised that it was Brahma. At his request, Sakka recounted the eight glorious features of the Lord. Thereupon Brahma materialised himself and appeared to the gods as Pancasikha (five-headed). He remained suspended in space and sat cross-legged.

7th JANUARY

hitva mamattam manujesu brahme

ekodibhuto karunadhimutto…

pappoti macco amatam brahma-lokan ti

BRAHMA then narrated the following story:

Once upon a time there was a king named Disampati who had a wise brahmana minister named Govinda. Reņu was the king's son; Jotipala was Govinda's son. They and six other nobles were close friends.

In course of time Govinda died. The king was distressed, but Reņu said to his father: "Grieve not, father. Appoint Jotipala to his father's office, for he is even wiser than his father." The king did so, and soon Jotipala earned a very good reputation as a great administrator. He noticed that the king was getting old. One day he said to the six nobles: "Go to prince Reņu and tell him, 'The king is old and who knows when the end will come. When he dies, we pray that prince Renu should be king."" They did so. Prince Reņu responded: "Well, if I become king I shall share the kingdom with all of you."

Some time later the king died and Reņu was crowned king. But he was given to sensual pleasures. Maha-Govinda (Jotipala) went to the six nobles and persuaded them to remind Renu of his promise to share the kingdom with them. Renu readily agreed and with the help of Maha- Govinda divided the kingdom between himself and the six nobles. All the seven of them requested Maha-Govinda to be their minister and rule the kingdoms.

In the meantime, Maha-Govinda's reputation was spreading every- where. People were even saying that he had seen Brahma face to face and talked to him. This reached Maha-Govinda's ears. He felt: "These are rumours. But I myself have not seen Brahma face to face, though I would love to. I have heard it said that if one were to remain alone during the four rainy months and to practise the contemplation of compassion, he would see Brahma face to face. I will do so." Having decided thus he went to the king, to the nobles, to the brahmaņa and to his forty wives, and told them all of his decision to live alone, with- out seeing anyone except the one who brought him his meals. He had a rest-house built for this purpose and entered into seclusion.

But the four months passed without his seeing Brahma. When at last he was overcome by great anguish, Brahma appeared before him. Maha-Govinda's worship was acceptable to the Lord and Brahma asked him to choose a boon. Maha-Govinda said: "By what said: "By what means can a mortal realise immortality?" Brahma replied: "Only that mortal can reach immortality who abandons all sense of 'I' and 'mine', who loves seclusion, who is full of compassion, who has eradicated foul odours and who is established in celibacy." Maha-Govinda asked Brahma: "I understand all the rest of thy teaching, but what are 'foul odours'?" Brahma replied: "Anger, falsehood, deceit, selfishness, pride, jealousy, greed, doubt, violence, lust, hate and dullness. These are the foul odours, and under their influence man is doomed to hell and shut out from the realm of Brahma." Maha-Govinda responded: "If I understand the Lord aright, it is impossible to get rid of all these while living as a house- holder; this means I should enter the homeless state."

8th JANUARY

idam kho pana me pancasikha brahmacariyam ekanta-nibbidaya

viragaya nirodhaya upasamaya abhinnaya sambodhaya nibbanaya

samvattati

BRAHMA continued:

Maha-Govinda went to see king Reņu and announced his decision to enter the homeless life. The king tried to persuade him not to do so, offering to fulfil all his wishes and to provide whatever he might need. "I need nothing for my happiness and there is no one that has hurt me. I have heard the call and I must go," said Maha-Govinda. The king decided to follow Maha-Govinda's example.

Maha-Govinda then went to see the six nobles. When they heard of his decision they took counsel among themselves and thought: "These brahmaṇa are greedy for money and they have a passion for women; let us offer him these and he might abandon his idea.' They made these offers. But Maha-Govinda replied: "I have all the wealth and possessions I need. I have forty wives already. I am giving all that up in order to enter the homeless state." The nobles, too, decided to follow him, but they needed time! They pleaded with him to wait seven years, but he declined, so they pleaded for a delay of six, five, four, three, two or one year, down to seven days. Maha-Govinda agreed to a delay of seven days.

Maha-Govinda then went to see the great brahmana and his students and exhorted them to seek another teacher, as he was entering the home- less life. They tried to dissuade him, but without success. They, too, decided to follow him. Maha-Govinda then went to his forty wives, announced his intention and gave them leave to marry someone else. But they decided to follow him.

By this time the seven days were over and Maha-Govinda cut off his hair, donned the yellow robes and went forth into the homeless state. The king, the nobles and all the others followed him; thousands of citizens also joined them. Wherever he went with his retinue he was welcomed and honoured like a king of kings, or a deity. Maha-Govinda radiated love, compassion, joy and equanimity to the four quarters of the world, and he taught his disciples the way to union with Brahma. After their death all of them were reborn in the world of Brahma.

Pancasikha, who was narrating all this to lord Buddha, asked the Lord: "Do you remember all this?" The Lord replied: "Yes, indeed I do. I was Maha-Govinda. It was then that I taught my disciples the way to union with Brahma. However, that religious life is not conducive to nibbana. But my religious system is conducive to detachment, to freedom from_passion, to cessation of craving, to peace, peace, to insight to insight and to nibbana. This is the noble eightfold path. Those of my disciples who are completely free from the asava are liberated. They who do not wholly understand, but who are free from the five fetters, will not return to this world. Some others will return just once. Many will not be reborn in a state of woe. My disciples' renunciation of the home- life is not in vain. In every case it has been fruitful.

9th JANUARY

The future buddha as bodhisatta was incarnate as a 'tree divinity' in the kingdom of Kasi when Brahmadatta was king. In that kingdom there were very many pious and religious brahmana. One of them resolved to perform a rite to propitiate his departed ancestors.

This brahmana said to his disciples: "Take this goat to the river, bathe it and adorn it with garlands. Then bring it back to me, to be sacrificed to propitiate my ancestors." They bowed to him in obedience and took the goat away to the river.

On account of some merit it had earned in a past lifetime, the goat remembered what it had done then. Recollecting those events, it was filled with joy in the knowledge that its life of sorrow was soon to end. It laughed aloud. Then the goat thought of the brahmana and what he was about to do. Considering the consequences of the brahmana's deed, the goat began to weep aloud.

The young disciples were astonished at this and asked the goat: "Friend, why did you laugh, and now why do you weep?" By this time they had reached the master's house. And, the goat narrated the follow- ing story of its own past:

"In a previous lifetime I, too, was a brahmana. Like you, I too offered a sacrifice to propitiate departed ancestors, as enjoined in the veda. In that sacrifice I killed a goat. For that sinful action I had to suffer: four hundred and ninety-nine times my head has been cut off. This is the five hundredth and last time. When I have paid the penalty this time, I shall be freed from sorrow. Thinking of this I laughed. But, then, the thought occurred to me that you, who are taking my life in a similar way to propitiate your ancestors will similarly suffer an unhappy destiny. When this thought arose in me, I was filled with compassion and so I wept aloud."

Hearing this story, the brahmana was awakened and he declared: "I will not offer this goat in sacrifice." But the goat responded: "Even then I cannot but pay the penalty ordained for me, though by desisting from killing me, you will be saved from an evil destiny."

The goat was set free. It was grazing near the top of a rock. There was a storm, thunder and lightning. Struck by a thunderbolt the rock was shattered; a piece of rock knocked off the head of the goat.

The bodhisatța, who as the 'tree divinity' was observing all this, manifested himself as a celestial being and instructed all those present: "If only people understood what an evil destiny follows the taking of life, then they will surely desist from such cruelty." He discoursed at great length on the evil of killing. The people who heard him were so greatly inspired that they abandoned killing and cruelty, and resorted to loving kindness and charity.

10th JANUARY

Once upon a time the bodhisatta (future buddha) was born as a dog and lived in a cemetery, with a huge pack of dogs. One day the king of that region had returned from a ride to the pleasure garden, and his chariot had been left in the open courtyard unattended, with the harness and leather-work exposed. It had rained during the night and this had tempted some dogs to gnaw at the harness and ruin it.

This was duly reported to the king who ordered all the dogs in the region to be slaughtered. The news reached the bodhisatta who contemplated deeply and realised the truth: that it was the king's own pet dogs which had been responsible for the damage and that other dogs were being punished unjustly. So, he sought the presence of the king.

To the bodhisatta's questions, the king admitted that he indeed did not know for certain which dogs had committed the crime. The bodhisatta then asked the king: "Have you then ordered that all dogs should be killed?" "No," replied the king, "the palace dogs are spared." The bodhisatta quickly pointed out: "Then you are guilty of the evils of partiality, dislike, ignorance and fear. These four evils are unworthy of you, a king. The privileged dogs are safe; the poor are slaughtered."

The king then asked the bodhisatta: "Do you know which dogs committed the crime?" The bodhisatta replied: "Yes" and went on to prove his affirmation. He had a mixture of butter-milk and kusa grass prepared. He made the palace dogs drink of this mixture. This induced vomiting in the dogs, and the vomit contained pieces of leather proof that those dogs had indeed chewed the harness.

The king rejoiced that justice had been vindicated. He at once halted the slaughter of the dogs. He paid due homage to the bodhisatta who then taught the dhamma to the king and all his followers. The king commanded that no one should thenceforth harm any living creature in his domains. He himself adhered to the noble teachings of the bodhisatta and spent the remainder of his life in charity and righteousness.

10th JANUARY

In another era the bodhisatta was born as an ox who, with his younger brother, served a landlord. The brother-ox noticed that a pig named Munika was being feasted every day and that the oxen who did all the hard work were not so well looked after. The brother-ox bitterly complained about this to the bodhisatta who recommended patience. A few days later the family of a young man to whom the king's daughter had been betrothed arrived. There was a lavish banquet. The pig had been cooked. The bodhisatta pointed this out to his brother: "Poor Munika was eating his own death! Be contented with your poor fare which, however, signals your longevity."

11th JANUARY

In another era the bodhisatta was born as the only son of a royal couple. He was known as Maha Silava. Appropriately, he grew up to be a boy of excellent character and, later still, a king of personified goodness. His charity knew no bounds. Even when he himself had found out that a minister had behaved treacherously, he refused to punish him but requested the minister to leave the country with all his wealth and his family. This minister became the confidant of the ruler of the neighbouring kingdom and, knowing that Maha Silava was extremely soft-hearted advised him to invade, conquer and annex that kingdom, too. To prove his point the ex-minister advised the rival king to send a few brigands into Maha Silava's territory to murder and plunder.

The villains were caught and brought before Maha Silava. They said: "We did this because we did not have enough to eat." The king instantly pardoned them, loaded them with wealth and sent them back. This ruse was repeated_by several other parties. The rival king was convinced that Maha Silava was timid and weak. He invaded Maha Silava's kingdom. Informed of this, Maha Silava preferred defeat to destruction, and refused even to defend the palace. The rival usurped the throne and mercilessly captured Maha Silava and his ministers and had them buried up to the neck in a clearing in the forest.

Maha Silava was full of patience and perseverance. One night a pack of jackals rushed towards him and his ministers, who raised such a loud cry that they ran away. However, the leader of the jackals returned to try again. As the jackal came close to him, the king stretched his neck and with his jaw caught the neck of the jackal. The frightened jackal, in an attempt to free itself, thrashed about with his legs and thus loosened the earth around the king. The king let the jackal go, and soon freed himself and the others.

At the same moment, a couple of goblins nearby approached Maha Silava and, recognising his greatness, requested him to divide a dead body they had acquired, equally between them. The king, however, made use of their magical powers to bathe and dress himself, and even to retrieve the royal sword before dividing the body equally between the two goblins. Seeing that they were greatly pleased, he asked them to take him and leave him in the royal bedchamber, and similarly to take all his ministers and leave them in their former residences. This, too, was done.

The usurper was surprised to see Maha Silava enter the bed- chamber, though the palace was heavily guarded. Maha Silava narrated all that had happened. The usurper was stricken with remorse and begged Maha Silava to pardon him. He said: "Though born of royal parents, I failed to recognise your greatness, whereas even goblins recognised it." He vowed to be Maha Silava's friend. Soon he summoned all his Own ministers, confessed his error before all, and restored the kingdom to Maha Silava. On that occasion, Maha Silava declared the profound truth: "If you do not abandon patience and right effort, your reward will be great and excellent."

12th JANUARY

Once upon a time, the bodhisatta was born as a hare in a forest. He cultivated the friendship of an otter, a jackal and a monkey who looked up to him as their spiritual leader. He taught them wholesome lessons in right living, in charity and in religious observances like fasting.

One evening the hare addressed his companions: "Tomorrow is a fasting day when it is good particularly to do charity and observe the rules of right living. Should a guest happen to come to you, please ensure that he is attended to." The otter, the jackal and the monkey thereupon went out out to find food with which to entertain the unexpected guest. Each one obtained something or the other. The hare in the meantime had nothing other than grass; but he reflected thus: "Surely, if a guest happens to come here, I cannot offer him grass. But, I shall offer him the flesh of my body." This great resolve was 'heard' in the heaven. Sakka, the lord of heaven, wanted to test the strength of the hare's resolve. He disguised himself as a brahmana and came to the forest.

The brahmana went to the otter, the jackal and the monkey, and each of them offered him the food that they had acquired that day. But, he walked on, without accepting the offer or rejecting it. Then he went to the hare who welcomed the honoured guest and offered hospitality. He said: "Holy one, I have nothing but grass to appease your hunger. But if you will be gracious enough to accept it, I offer you my own flesh. Please kindle the fire and I shall enter into it and you can eat my flesh which will give you the strength to carry on your religious practices." The lord of heaven was still not convinced. He raised the fire. The hare went round the sacred fire and then with great joy and eagerness leapt into it.

But the flames were cool. Surprised, the hare spoke to the lord of heaven disguised as a brahmana: "What does this mean, O brahmana?" The lord of heaven revealed his identity and glorified the self- sacrifice of the bodhisatta.

The bodhisatta was once born as a lion. One day a jackal approached him and asked to be admitted as a servant. The lion agreed and said: "Run up a hilltop and when you see a prey, shout aloud: 'Let your might shine, Lord' and it shall be a signal for me to attack the prey. You will have your share of the meat." Thus they lived for a time. One day the jackal thought: "After all, it is the charm of my words that enables the lion to kill! I am equally powerful. Why should I not kill, instead of having to live on others' leavings?" Though the lion cautioned him that only lions could kill elephants, the foolish jackal insisted on making the kill. The jackal leapt on an elephant, missed its head and landed at its feet. Trampled by the elephant, it lay dead, the victim of its own delusion and pride.

13th JANUARY

During another era the bodhisatta (future buddha) was born as a quail. He was the leader of a thousand quails that lived in a forest. A clever fowler often spread a net, caught very many quails and took them away.

One day the bodhisatta spoke as follows to the quails in his retinue: "If you live and work in harmony we can all escape the fowler's net. Please do as I tell you. When the fowler throws his net over you, stick your head through the mesh of the net and, at a pre-arranged signal, fly away with the net. Land on a thorn bush and then extricate yourself from the net. If all of you function in total harmony, no harm will befall you." And, the next day they did so; the fowler got nothing and even his net was damaged by the thorn bush. Day after day the same thing happened. But the fowler was still hopeful; for he knew that such unity may not endure for long and when the quails were disunited and quarrelled among themselves, they would be an easy prey.

And so it happened. One day one quail happened unwittingly to tread on another's head. The second one got angry. A bitter quarrel ensued. Noticing this the bodhisatta decided to leave that place along with his followers. He knew that there was no security in a house divided against itself.

The next day the fowler returned with his net. The birds began to argue amongst themselves: "Why should I lift the net? You better do the job today" and so on. Soon all of them ended in the fowler's basket: the fruit of disregarding the bodhisatta's call for unity and harmony.

Once upon a time, the bodhisatta was born as a pigeon. A wealthy jeweller adopted this pigeon and provided it with a basket in his kitchen where the pigeon lived happily. One day a crow smelt the rich food being cooked in the kitchen. It met the pigeon and tried to befriend it. The bodhisatta tried to dissuade the crow, saying: "Your food and my food are very different. My company may therefore not be very congenial to you. You will have to abandon all greed and be contented with simple fare." But the crow insisted that it would be content with whatever it got. The jeweller decided to accommodate the pigeon's friend, too.

One day the pigeon was getting ready to fly out in search of food. The crow pretended to have a stomach-ache, for it had seen a potful of fish in the kitchen! After the pigeon had gone away, the crow began to eat of the fish. However, it was discovered by the cook who caught hold of the crow and pulled out all its feathers. The greedy crow who did not heed the good friend's advice perished.

14th JANUARY